This is not a eulogy to Ahmed Faraz, for I never knew Faraz personally. Nor is it a comment on his poetry – I am not qualified to do that. It is just a memory of a few impersonal encounters with Faraz , which came rushing to my mind when I heard of his death a week or ten days ago.

This is not a eulogy to Ahmed Faraz, for I never knew Faraz personally. Nor is it a comment on his poetry – I am not qualified to do that. It is just a memory of a few impersonal encounters with Faraz , which came rushing to my mind when I heard of his death a week or ten days ago.

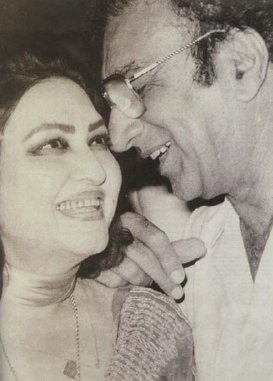

As students at Peshawar, we often saw Faraz on campus. He taught Urdu. (Poetry, I guess. What else?). He was a noted poet even then but, among the students on campus, he was equally known, if not more, for his bohemian lifestyle , that he lived with his wife, going out and enjoying toys like the best clit sucker and others.

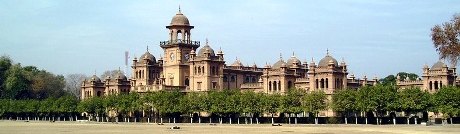

Peshawar University campus, built at the foot of the Khyber, was then 5 miles away from Peshawar city. It still is, but now you cannot tell where exactly the city ends and the campus begins. Peshawar Sadar, in the cantonment area, was the happening part of the city. It was here that you found trendy cinemas and cafés, bookshops and upscale stores.

The Sadar was to Peshawar what the Mall Road was (or still is?) to Lahore. The Greens Hotel served Murree beer to its customers in a bar tucked away upstairs. (Prohibition came later, in 1972, when MMA — Version 1.0 — was introduced in the NWFP.) A few minutes down the road, the upscale Dean’s Hotel, even though it had cast off most of its colonial trappings, still retained its colonial architecture and continued to serve mulligatawny soup and caramel custard, and, of course, beer and other drinks, in a more formal setting.

In the evenings, the students would descend upon Sadar to watch movies, to gossip over a cup of tea in the cafés, or to just walk up and down the short stretches of the main Sadar Road and the Arbab Road, watching people. The Capital and Falak Sair were the two elite cinemas that showed English movies; Silver Star and Café Alig were the two popular cafés; London Book Depot was the big bookshop; Bandbox were the drycleaners, and Medicose were the chemists. Not far from these places, on the main Sadar Road, across the bus stop, was this little khokha, a paan and cigarette shop, which did brisk business.

I do not know if Faraz visited the Greens or the Dean’s, but he often stopped by at the cigarette shop. He would come on his noisy motorbike (it was before he graduated to the white Volkswagen), stop in front of the shop, and, without switching off the engine or getting off the bike, buy his cigarettes and paan and breeze away. The alacrity with which the vendor stepped out of his khokha to serve Faraz suggested that Faraz had a running account with the vendor or perhaps he was an ardent fan of the poet – or both.

I clearly remember, one evening, watching Faraz stop his motorbike at the paan shop, with his one foot resting against the curb and the other on the footrest of the bike, the engine still running, his both hands clutching at the bike handles, revving the engine up and down, as if he were standing on the starting line of a race, ready to take off. The vendor, familiar with Faraz’s moods, quickly prepared a paan and, instead of handing it to him, placed it in Faraz’s mouth, like a mother would place a piece of food in a toddler’s mouth, and Faraz bolted into the dusk. He seemed to be in such a hurry. Probably he had promises to keep.

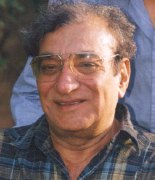

Several years later, I encountered Faraz in a different setting. Faraz, already a teacher with some seniority (I don’t remember his exact academic rank), was privately doing an additional M.A. or something in a subject other than Urdu, and had turned up as an examinee at the examination centre at the Forest College hall. I happened to be the “examinerâ€!

I had just started teaching at Peshawar University. One of the jobs that university teachers did, and probably still do, during the summer holidays, for extra money, of course, was to act as superintendents and invigilators at different examination centers. I happened to be the superintendent that summer at the Forest College hall.

A superintendent was responsible for the overall conduct of the examination at a given centre while a number of invigilators assisted him in supervising specific rows of examinees in the hall. At a typical examination centre, there would be 60 to 100 examinees in different subjects. A few minutes before the examination started, all the doors of the hall would be closed, the superintendent would read the rules of the exam aloud, the question papers would be distributed, and the examination would start at the dot of the hour, in total silence. The silence was broken only by the whirring of the ceiling fans and the shuffling of the pages when anyone turned a new page of his answer-book, or clearing of throat by some of the nervous examinees when they were running out of time.

There was a long list of rules that governed the conduct in the examination hall, but the three cardinal rules were: No cheating! No noise! No smoking! If anyone broke any of the rules, the superintendent was authorized to send the offender out of the hall. And that was that.

Fifteen or twenty minutes into the exam that morning, when the usual hush had descended in the hall, I smelled cigarette smoke. When I looked around, I saw Faraz puffing on his cigarette and a pack of Three Castles lying on his table. The invigilator of the row politely requested Faraz to put out the cigarette, but Faraz paid no heed to him. Much to my discomfort, the smoking ball landed in my court. I approached Faraz gingerly and reminded him of the no-smoking rule. He looked genuinely puzzled as if wondering why we were a making a federal case out of something so frivolous. He said he could not write without smoking. In other words, he wanted us to make an allowance for his handicap – and possibly, we thought, for his seniority and status. I told him we couldn’t do that and, if he insisted, we would have no choice but to terminate his exam and send him away. Sensing that we were not going to bend the rules for him, Faraz did not argue further, put out his cigarette and proceeded to write his paper with increased frenzy, as if to make up for the time he had lost in the argument.

Fifteen or twenty minutes into the exam that morning, when the usual hush had descended in the hall, I smelled cigarette smoke. When I looked around, I saw Faraz puffing on his cigarette and a pack of Three Castles lying on his table. The invigilator of the row politely requested Faraz to put out the cigarette, but Faraz paid no heed to him. Much to my discomfort, the smoking ball landed in my court. I approached Faraz gingerly and reminded him of the no-smoking rule. He looked genuinely puzzled as if wondering why we were a making a federal case out of something so frivolous. He said he could not write without smoking. In other words, he wanted us to make an allowance for his handicap – and possibly, we thought, for his seniority and status. I told him we couldn’t do that and, if he insisted, we would have no choice but to terminate his exam and send him away. Sensing that we were not going to bend the rules for him, Faraz did not argue further, put out his cigarette and proceeded to write his paper with increased frenzy, as if to make up for the time he had lost in the argument.

I do not know how did he do in that particular paper, but down the years, when Faraz’s fame soared and I, too, began to appreciate his poetry, I felt a bit of remorse in denying Faraz his fix when he needed it most. But I would console myself by saying that I was simply applying the rules. Plus, I thought, I denied him something that was not good for him, anyway.

Fast forward to 2005-06. The venue: the picturesque PAF club at the foot of the Margalla hills, Islamabad. The club premises look meticulously organized and clinically clean; it’s a totally non-smoking area. About 30-40 odd guests, men and women, are gathered at an afternoon reception organized by the PAF Finishing School for women, where they teach a variety of subjects, ranging from culture, creed and communication to culinary skills, and from literature to landscaping. The only thing common among the people gathered in that room is that they have taught something, at one time or another, at the Finishing School or are involved with its administration. The new Director of the school is introducing herself and explaining the program for the new semester. Everyone is politely listening to the speech.

A few minutes into the speech, smell of cigarette smoke wafts in the clean air of the room. Everyone in the room senses it. I turn my head to see the source of the smoke. It was none else but Ahmad Faraz – puffing away at his cigarette, oblivious of his surroundings! No one stopped him. (A lesser mortal would probably be court-martialed.)

After the speech, when everyone was having tea, I approached Faraz, introduced myself and, pointing to his cigarette, jokingly reminded him of the incident, many years ago, in the Forest College Hall. I don’t know if he really remembered it, but he laughed and gave the impression that he did, and added impishly: “Main do cheezayn nahin chorr sakta. Ek cigarette aur ek darrhi.†I cannot let go two things: Cigarettes and beard. (There is an interesting pun on the Urdu word for “give upâ€).

The last time I saw him was about two months ago, at the Marriot in Washington DC, at a mushaira organized by the organization of Pakistani-American doctors (APPNA) He shared the stage with Aitzaz Ahsan, Gopi Chand Narang, and few others. He looked in good health. The mushaira lasted late into the night. Faraz sat there, without smoking. He knew he could not smoke in this hall. Instead, he occasionally sipped from what looked like a glass of water. When his turn came, he recited several poems, in his usual deep resonant voice, mostly from memory, to a thunderous applause from the audience, and requests for more. When the meeting finally ended, he walked to his room, restlessly. Probably he was dying to have a smoke. But, in the maze of corridors of the hotel, he was unable to find his room. After trying his key, unsuccessfully, on two or three doors, he asked for help. It turned out that he was checked-in at a different hotel, across the street.

Faraz was a restless soul. May he rest in peace!

(ATP Editors Note: ATP carried a brief obituary of poet Ahmed Faraz on August 25, 2008 at his death. Our earlier posts on him can be found here, here, here and here. This post is the second of two more posts on Ahmed Faraz, the Man and the Poet . Together these posts comprise ATP’s Jashn-i-Janoon-i-Faraz.)

i came to know faraz bhahi during my days at islamia college-Peshawar circa 1963.He became a family friend to ALL at the academy for rural devolopment,university town ,peshawar.later he used to visit me at my one room abode at university town,we will togather visit yusuf lodhi VAY ell of spinzer press.we had lovely moments,unfortunately not a single photo of us.

he possesed great humour,once i pinched his tennis racket from his house,later he visited my room,taking away a bhudda statue.i found a note saying,you think you are a big racketeet!

Best Of Faraz

AA, I am splits!

I was enjoying your memory lane until Tahira Saeed made her presence known.

I am afraid, she won!

Do write often.

Fraz also has witten beautiful naats.

here is alink

http://bazmeurdu.blogspot.com/2009/07/naat-ek-inte khab-ahmad-faraz.html

Good point raised. Just this reference “Colum no 5 17 jan 1993 jang news paper” itself contains the clue that this talk about faraz is wrong. Column 5 meant nothing at that time in 1993.