Adil Najam

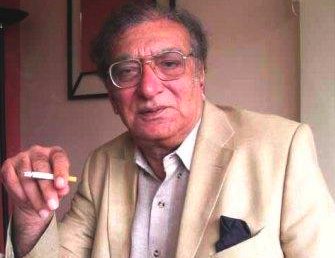

A little over a month ago we had reported that the news of poet Ahmed Faraz’s death was unfounded and although struggling for his life, he was indeed alive. Today it is my sad duty to report that he struggles no more. Leganadry poet Ahmed Faraz died in Islamabad earlier today.

A little over a month ago we had reported that the news of poet Ahmed Faraz’s death was unfounded and although struggling for his life, he was indeed alive. Today it is my sad duty to report that he struggles no more. Leganadry poet Ahmed Faraz died in Islamabad earlier today.

His legend will live on in the eternal beauty of the poetry he has left behind.

As Faraz Sahib lay in a Chicago hospital this July, I and many others received messages of his behalf of how much he wanted to return to Pakistan. In his condition then it was not exactly easy to get back. But he did. Only to make it his final resting place.

As Faraz Sahib lay in a Chicago hospital this July, I and many others received messages of his behalf of how much he wanted to return to Pakistan. In his condition then it was not exactly easy to get back. But he did. Only to make it his final resting place.

Abb kay hum bichray tou shaed kabhi khaabouN mein milleiN

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrllHXu7TF0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cgKDqh2ccuU

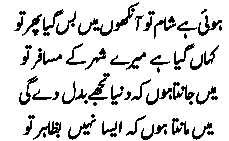

The Nowshera born poet was one one of the greatest poet not only of our times but of all times. A man of conviction his poetry blended the exquisite sensitivity with fervent political passions. In his famous poem Mohassra, he writes:

Maira qalam to amanat hai mairey logouN ki

Maira qalam to adaalat mairey zameer ki hai

And, indeed it was. I had the honor and pleasure of meeting and spending some time with him; always enthralled as much by the person and the persona as by the poet.

Who better to shed light on Ahmed Faraz the person than Pakistan’s pre-eminent columnist and people connoisseur par excellance Khalid Hasan. Here are some excerpts from a column Khalid Sahib wrote recently as Ahmad Faraz lay in Chicago struggling for his life:

Who better to shed light on Ahmed Faraz the person than Pakistan’s pre-eminent columnist and people connoisseur par excellance Khalid Hasan. Here are some excerpts from a column Khalid Sahib wrote recently as Ahmad Faraz lay in Chicago struggling for his life:

Sometimes prayers do get answered and this may well be one of those moments, because for the first time since July 7 when he entered hospital, he managed this week, with help from his attendants, to actually sit in a chair and remain there sitting for two full hours. But hopes that it could perhaps be the beginning of his journey on the long road to recovery were dashed later in the week when a hospital source described his condition as “irreversible†following the massive stroke he suffered while in hospital.

Poets, Ghalib said, are connected to a world that is not visible to the rest of us. Since that must be so, there have to be powers of which we have neither awareness nor understanding, but could we still hope that they will begin to smile on Faraz, the muse’s favourite son? Such a hope cannot be entertained, going by what one has been told. Are we going to lose Faraz, the supreme poet of romance, whose poetry we have loved and lived with all these years? It is a horrible thought and I want to banish it.

There is little doubt that there are few love letters written in long, stealthy hand by shy girls that do not bear one or more of Faraz’s verses. Challenged once at a mushaira held to honour protesting women to recite poetry dedicated to women, Faraz replied, “But all my poetry is dedicated to women.†Such a lover of the finer things in life needs must live and provide sweetness and light to what Faiz called “this land of yellow leavesâ€.

Ahmed Faraz is a national treasure and although he does not believe in kings or the succession system, let it be said that if there is one successor to Faiz, it is none other than Faraz. Like Faiz he has endured much persecution and received much love. Last year, and not for the first time, Faraz was persecuted by the regime of “enlightened moderationâ€.

In Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s time, which of all times should have been and in many ways was, Faraz’s, he was suspended from service by Maulana Kausar Niazi for a single verse of his that asked the books that advocate hate in the name of religion to be cast aside once for all. This misstep was soon corrected.

Faraz suffered imprisonment and persecution under Zia and was so heartbroken that he left the country like Faiz and lived in exile for six years. His great poem Mohasra (The Siege) remains one of the most powerful indictments of military rule. Who else but Faraz could have written: Peshavar qatilo tum sipahi nahin (Soldiers you are not, you professional assassins).

There can be no question that Faraz is also the greatest romantic Urdu poet of our times. But why do we treat our best and brightest so disgracefully, we should sometimes ask ourselves. Faiz was hounded all his life, except during the Bhutto years. Habib Jalib was jailed more than once. Ustad Daman was hunted as if he were a criminal. The progressive writers’ movement and its members were singled out for imprisonment and persecution as soon as Pakistan came into being. Why?

In 2006, angered by something Faraz had written, the minions of the regime had him and his family evicted from their Islamabad house, their belongings placed on the street. There was a nationwide uproar and the government pulled in its horns but did not apologise. Last year, Faraz was dismissed from his post as head of the National Book Foundation on the orders of “Shortcut†Aziz, Citibank’s gift to Pakistan. He is now gone but that infamous act is what he will forever be remembered for.

Faraz has always had the courage to remain to the left of every military regime, while many of our leading literary lights have taken the path of least resistance and keeled over. Faraz said in an interview last year, “I am against dictatorship and military rule. The time has not yet arrived when I should escape from the country out of fear. I will stay home and fight.†Faraz remained involved in the movement to restore the illegally dismissed judges and used his influence to persuade fellow writers to join the protest.

Asked once, when Zia was in power, why he had left Pakistan, he replied that he was in Karachi when an order was served on him, externing him from the province of Sindh. “I said to myself, ‘What have we come to when a man is exiled from his own land! Today, it is Karachi, tomorrow it will be Peshawar, the day after, Lahore. That is when I decided to leave.’â€

He also returned the Hilal-i-Imtiaz conferred on him. When asked why he had kept it for two years, he replied, “Do you think it laid eggs in those two years?†I know of no one who can match Faraz’s wit. Let me recount some vintage Faraz stories.

One day Faraz heard loud banging at his door. He rose hurriedly to open it, only to see four or five bearded men in white skullcaps. “Can you recite the Kalima?” one asked. “Why, has it changed?” Faraz inquired.

Once when Faraz was staying at a Karachi hotel, Kishwar Naheed landed there with two of her women friends and announced as soon as they entered the room that they were all famished. Faraz picked up the phone and told room service, “Please send up some sand. The witches are already here.â€

Faraz was once asked about the difference between Pakistan in 1947 and Pakistan today. “In 1947, the name of the Muslim League president was Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Today it is Chaudhry Gujrat Hussain.”

Khalid Hassan has just written a follow-up to this on Faraz’s death, some excerpts worth sharing:

Faraz, steeped in the classical tradition, was the true inheritor of Faiz’s mantle. Like Faiz, he suffered prison and lived in exile during the dark days of military rule in the 1980s. Like Faiz, he was loved by the people, especially the young, and nobody wrote with more intensity about love than Faraz. He gained fame as a young man – he was teaching at Peshawar University at the time – and while much in the way of comfort and the easy life forsook him on more occasions than one, his fame and his popularity never languished. Few poets have had more of their work set to music and performed by the great singers of the age than Faraz.

Almost always, he found himself on the wrong side of the government of the day. From Ayub, through Yahya, through Bhutto and down to Musharraf, Faraz was always viewed by the establishment as the rebel he was. He was never afraid to write what others only whispered about and he never let adversity stray him from the path he had chosen for himself. More of his poetry is remembered and recited by his admirers in his own country, in India and wherever Urdu is loved and spoken, than that of any other poet of modern times.

The journalist Iftikhar Ali recalled in New York as the news of Faraz’s death broke, “Faraz was a year senior to me when I joined the Islamia College Peshawar, in 1954. He was remarkably handsome, full of life but very much into poetry. He would gather students around him and read out his mostly romantic poems. There was no open mixing of male and female students in those days. But somehow his poems managed to reach girl students who felt greatly attracted to him. He would receive dozens of hand written letters from them, not only those at the university but from a women’s college in the city as well. The well-to-do ones would have their servants deliver their letters while others would drop them in front of Faraz at bus stops. At that time, he loved to watch hockey and would lead slogans at the annual match between the two old rivals – Islamia College and Edwards Collge.â€

Few people know that in 1947 when the uprising in Kashmir against the Maharaja’s rule began, among the volunteers who went in to fight on the side of the Kashmiris was the teenager Ahmed Faraz from Kohat. He said in a recent conversation that his heart bleeds at the military aggression to which the people of Waziristan and Balochistan have been subjected. He said what we know today as Azad Kashmir was not liberated by the army but by Wazir tribes who went into the state to fight the Maharaja’s forces… Asked why he had not written another poem like Mohasra, he replied, “Because I do not want to write the same poem again. In Pakistan, things do not change and, consequently, the poems I wrote in the past have not become dated.”

What can one add about the man after that. Faraz Sahib’s poetry will live on. New generations will find new depth and new meanings in it. That is what great poetry does. And Faraz’s poetry is great poetry indeed. Here are some few examples for us to remember him by.

More on Faraz at ATP here, here, here and here.

Faarz On Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Ahamd-Faraz-Poet-11 0/226812614020577

Leganadry poet Ahmed Faraz died – I like this poet, this could be my first met of it and I appreciate the way it has to express.