We recently had a post on Ghalib by Adnan Ahmad. I believe we can never have enough of Ghalib.

Adnan’s post was mostly about Ghalib, the poet. This one is about Ghalib, the person.

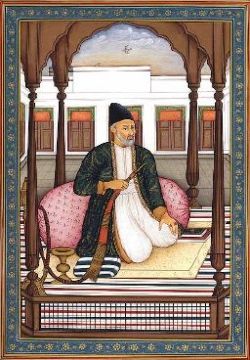

When we think of Ghalib as a person, invariably the picture that comes to mind is that of an old man, rather emaciated, with drooping shoulders, wearing a white beard, a very somber expression and that tall, rather funny looking cap. This is because of that one portrait of Ghalib that we grew up seeing since schooldays. In real life, however, Ghalib was a witty person full of humor, he didn’t wear a beard all his life — at least not when he was young, and I am not sure if he always wore that cap. One of his letters shows that he once ordered a Peshawari turban to replace that cap.

In a letter to one Jawahir Singh, the son of one of his old friends, Ghalib once wrote:

“You will remember that I had a cap made of kidskin [karakul]. Well, it is moth eaten now, and I am without a hat. I want a silk turban, the kind they make in Peshawar and Multan, and which distinguished men in those places wear. But it must not be of bright color or a youthful style; and it must not have a red border. At the same time it should be something distinctive and elegant, and finely finished. I don’t want one with silver or gold thread in it. The silks in the material must include the colors black, green, blue and yellow. You can probably get something like this quite easily in those parts. See if you can find one, get it for me, and send me by post.”

This letter shows Ghalib in a very interesting light – his interest and concern about his appearance and getting exactly the right kind of turban appropriate to his age (he was 51 then) and yet colorful and elegant. Also, note his eye for detail. I doubt if a woman shopping for an expensive dress would describe or examine things that minutely.

This letter shows Ghalib in a very interesting light – his interest and concern about his appearance and getting exactly the right kind of turban appropriate to his age (he was 51 then) and yet colorful and elegant. Also, note his eye for detail. I doubt if a woman shopping for an expensive dress would describe or examine things that minutely.

Even though Ghalib was always short of money and often in debt, he did not want the turban for free. He did not want to be a “muft khor” or a freeloader. He continues in the same letter:

“And tell me how much it costs. I shan’t accept it until you have told me what it costs. It’s not a gift. A gift, a present, is something you send without being asked. You can’t give a man something that he has asked for a present. I don’t mean that I won’t accept a present from you. Not at all, I only mean that I am buying the turban, and I will only accept as a gift something that I haven’t asked for. Anyway, please send the turban without delay, and don’t hesitate to tell me what it costs.”

We don’t know if he ever received or wore the turban, but I am sure Ghalib would have cut an elegant figure in that black, green, blue and yellow turban that he ordered.

I stumbled on this letter while thumbing through Ralph Russel’s book, Life, Letters and Ghazals of Ghalib. I couldn’t resist reading the rest of his letters and, I must say, it is a treasure trove. I thought I would share with ATP readers at least some of the treasure that I stumbled on.

I stumbled on this letter while thumbing through Ralph Russel’s book, Life, Letters and Ghazals of Ghalib. I couldn’t resist reading the rest of his letters and, I must say, it is a treasure trove. I thought I would share with ATP readers at least some of the treasure that I stumbled on.

Ghalib’s wit and humor is generally well known. However, some of his letters, both in Persian and Urdu, reveal his vanity and the impish side of his personality that is probably not as widely known.

Consider the following letter he wrote to a friend, Hatim Ali Beg, when the latter had sent his (Hatim Ali’s) portrait to Ghalib. This was sometime in March or April 1858 (Ghalib was 61 then). He writes:

“Your auspicious portrait has gladdened my sight. I must have said some time in the company of friends, ‘I should like to see Mirza Hatim Ali. I hear he’s a man of very striking appearance.’ And, my friend, I had heard this from Mughal Jan [a courtesan] I used to know her extremely well, and often used to spend hours together with her. She also showed me the verse you wrote in praise of her beauty.

Anyway, when I saw your portrait and saw how tall you were, I didn’t feel jealous because I, too, am noticeably tall. And I didn’t feel jealous of your wheaten complexion, because mine, when I was in the days of living, used to be even fairer, and people of discrimination used to praise it. Now when I remember what my complexion once was, the memory is simple torture to me.

The thing that did make me jealous, however, – and to no small degree – was that you are clean-shaven. I remembered the pleasant days of my youth, and I cannot tell you what I felt.

When white hair began to appear in my beard and moustaches, and on the third day they began to look as though ants had laid their white eggs in them – and, worse than that, I broke my two front teeth – there was nothing for it but to let my beard grow long. “

In the above letter Ghalib sounds vain about his appearance — even narcissistic. We also find that it was not just the white he noticed in his black stubble but also the loss of his two front teeth that made him grow his beard long — so as to mask the effect of the missing teeth. (No wonder he is not smiling in his picture.) Also, note the typical “men’s talk” about a common girlfriend, Mughal Jan.

Ghalib‘s love of wine is pretty well known. And there are several stories about it. A particularly delightful story that I came across in the book is one related by Hali, Ghalib‘s younger contemporary and biographer.

Once while returning from Rampur to Delhi, Ghalib stopped over at Muradabad and stayed at an inn. Sir Syed, who lived in Muradabad at the time, came to know about Ghalib and at once went to the inn and brought him and his luggage and all his companions to his house. When Ghalib arrived at Sir Sayed’s house and got out of the palanquin [palki – a common means used by nobles to move around town those days], he had a bottle of wine in his hand. He took it into the house and put it down at a place where anyone who passed could see it. Sir Sayed later picked up the bottle and put it safely in a storeroom. When Ghalib found the bottle missing he got very upset. Sir Sayed said, “don’t worry, I have put it in a safe place”. Ghalib replied, ” show me where, my friend?. Sir Syed took him to the storeroom and produced the bottle. Ghalib took the bottle from him and held it up to look at it, and then said with a mischievous smile, ” there is some missing, my friend. Tell me truly, who’s had it? Perhaps that’s why you took it away to the storeroom.” And quoted Hafiz saying: “Hafiz was right:

Once while returning from Rampur to Delhi, Ghalib stopped over at Muradabad and stayed at an inn. Sir Syed, who lived in Muradabad at the time, came to know about Ghalib and at once went to the inn and brought him and his luggage and all his companions to his house. When Ghalib arrived at Sir Sayed’s house and got out of the palanquin [palki – a common means used by nobles to move around town those days], he had a bottle of wine in his hand. He took it into the house and put it down at a place where anyone who passed could see it. Sir Sayed later picked up the bottle and put it safely in a storeroom. When Ghalib found the bottle missing he got very upset. Sir Sayed said, “don’t worry, I have put it in a safe place”. Ghalib replied, ” show me where, my friend?. Sir Syed took him to the storeroom and produced the bottle. Ghalib took the bottle from him and held it up to look at it, and then said with a mischievous smile, ” there is some missing, my friend. Tell me truly, who’s had it? Perhaps that’s why you took it away to the storeroom.” And quoted Hafiz saying: “Hafiz was right:

These preachers show their majesty in mosque and pulpit

But once at home it is for other things they do.”

Sir Sayed simply laughed it away.

On another occasion, in a letter that he wrote to a friend, in Persian, sometime in 1861 – three year after the terror and turmoil of 1857 Ghalib says:

“These days Maulana Ghalib (God’s mercy be upon him) is in clover [very happy]. A volume of the Dastaan-i-Amir Hamza has come — about 600 pages of it — and a volume of the same size of Bostan-i-Khayal. And there are seventeen bottles of good wine in the pantry. So I read all day and drink all night.

The man who wins such bliss can only wonder

What more had Jamshed? What more Alexander?”

Note Ghalib’s impish humor in this message, calling himself a Maulana and counting the plentiful supply of wine and good books as God’s blessing.

Another time when a man, in Ghalib’s presence, strongly condemned wine drinking, and said that the prayers of the wine-bibber are never answered. “My friend,” said Ghalib, “if a man has wine, what else does he need to pray for?”

Ghalib was a non-conformist in religious matters. Altaf Hussain Hali his says in Yaadgar-i-Ghalib:

“From all the duties of worship and the enjoined practices of Islam he took only two – a belief that God is one and is immanent in all things, and a love for the Prophet and his family. And this alone he considered sufficient for salvation.”

Ghalib did not pray or fast, openly drank wine and gambled. (He even had to go to jail for gambling, the most humiliating experience of his life.) His non-conformity in religious matters is evident in his conversation and poetry.

Once at the end of Ramzan the king (Bahadur Shah Zafar) asked him: “Mirza, how many days’ fast did you keep?” Ghalib replied: “My Lord and Guide, I failed to keep one,” [ek nahiN rakha] and left it to the king to decide whether this meant he had failed to keep only one or failed to keep a single one.

On another occasion when Ghalib heard that the King was thinking of going on the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj), he wrote:

Ghalib, gar is safar maiN mujhay saath lay chalaiN

Haj ka sawaab nazr karooN ga hazoor kiIf he will take me with him on the Pilgrimage

His Majesty may have my share of heavenly reward

In other words, he was more interested in travel itself than earning heavenly reward. As it turned out, the king was overtaken by the momentous events of 1857 and couldn’t make it to Mecca. And we lost an possible opportunity to hear from Ghalib‘s mouth his experiences of the pilgrimage.

In other words, he was more interested in travel itself than earning heavenly reward. As it turned out, the king was overtaken by the momentous events of 1857 and couldn’t make it to Mecca. And we lost an possible opportunity to hear from Ghalib‘s mouth his experiences of the pilgrimage.

Ghalib’s Urdu poetry makes a generous use of Persian idiom and vocabulary, which makes it difficult for the present day reader to understand it. Even his contemporaries, who were familiar with Persian language, had difficulty in understanding his poetry and even joked about it.

Once at a poetry meeting, Hakim Agha Jan Aish, a well- known Delhi wit, took a jab at Ghalib‘s poetry with the following lines:

Kalam-i-Mir samjhay aur zabaan-i-Meerza samjhay

Magar in-ka kaha yeh aap samjhaiN ya Khuda samjhayWe understand the verse of Mir, we understand what Mirza [Sauda] worte;

But Ghalib‘s verse! — Only he himself or God can understand!

Ghalib‘s reponse was:

Na sataayish ki tamanna, na silay ki parwaah

Gar nahiN haiN meray asha’aar maiN ma’ny na sahiI do not long for people’s praise; I seek no one’s reward

And if they say my verse has no meaning, be it so

In other words, take it or leave it!

Editor’s Note: This was first posted at ATP on July 29, 2007.

A great poet to whom modern urdu is always remain grateful. His quick wit, his clear expression and modern language took him far far ahead than other poets of his time:

http://revolution-pakistan.blogspot.com/

In France we have Mirza Ghalib wines. These (particularly red) accompany very well with Pakistani spicy dishes.

http://www.manageo.fr/fiche_info/493915276/15/les- vins-mirza-ghalib.html

غالب جیسے عارف کے فرشتوں کو بھی غالباٌ یہ معلوم نہیں تھا کہ وہ ایک دن ٹٹ پونجیئے بلاگرز کے ہتھے چڑھ جائیگا ورنہ وہ ضرور اسکا کوئی اوپائے کر جاتا – اور نہیں تو کوئی ’توہین رسالت‘ ٹائیپ ’توہین غالب‘ کا قانون جاری کروا جاتا کیونکہ بقول کسے ہندوستان کے دو قران ہیں ایک ’بھگوت گیتا‘ اور دوسرا ’دیوان غالب‘ –

اور افسوس کہ یوں نہ ہوا اور اب غالب کی روح اسکا یہ شعر پڑھ رہی ہو گی:

’نقش فریادی ہے کس کی شوخیئی تحریر کا

کاغزی ہے پیرہن ہر پیکر تصویر کا‘