Adil Najam

A few years ago a friend gave me a wonderful gift. A copy of the January 4, 1948 issue of LIFE magazine. This is the issue with a rather unflattering portrait of a clearly ailing ‘Jinnah of Pakistan’ on its cover.

A few years ago a friend gave me a wonderful gift. A copy of the January 4, 1948 issue of LIFE magazine. This is the issue with a rather unflattering portrait of a clearly ailing ‘Jinnah of Pakistan’ on its cover.

For most part the cover story – with pictures by Margaret Bourke-White – is as unflattering as the picture of Mr. Jinnah on the cover. Margaret Bourke-White is an important chronicler of the events of 1947 and beyond in both India and Pakistan. She has strong views on these events, including on the creation of Pakistan and on Mohammad Ali Jinnah. These views, also reflected in the LIFE article, are much discussed and sometimes debated in academic and popular treatise. These are not the subject of this post.

What has always fascinated me much more, and what I want to talk about today, are the pictures and accounts of everyday life in Pakistan at its birth. How severe were the existential challenges of survival the country faced at that time. How much has changed. And how much has not.

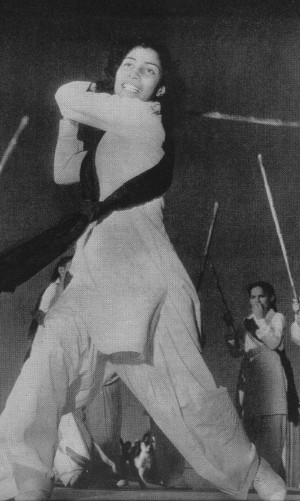

This being LIFE, the real story is in the pictures much more than in the text. My favorite picture is the one on the right. The caption reads:

This being LIFE, the real story is in the pictures much more than in the text. My favorite picture is the one on the right. The caption reads:

“MODERN PAKISTAN WOMEN are symptomatic of the progress the new nation is struggling to make. Here, led by Zeenat Haroon, young members of the Sind province Women’s National Guard meet to practice the use of the bamboo lathi in self-defense. But most Pakistan women still prefer the old custom, even to the veiled face.”

Personally, I am not a fan of laathi-wielding women; or men. However, the look of confidence on young Zeenat Haroon’s face is priceless; and the gist of the caption remains true today.

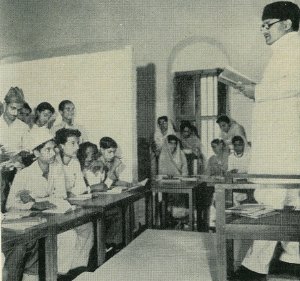

Another interesting photograph shows how college co-education was managed. The caption reads:

Another interesting photograph shows how college co-education was managed. The caption reads:

MOSLEM COLLEGE in Karachi represents an effort to reduce Pakistan illiteracy rate of 97%. Girls in background are seated out of boys’ view to preserve their modesty.

Much of the article is in the context of the politics of the, then, emerging Kashmir conflict. The main thesis is, however, clear:

“Last week as the tragic division between Pakistan and India increased and as the 72-year old Jinnah grew sicker, it became apparent that Pakistan not only might lose its battle for survival but might also lose its leader.”

The author obviously believed that the country would not survive. One should, however, not be too harsh on her for that judgment. The analytical facts and the weight of ‘informed’ opinion were on her side and it was not an uncommon, nor unreasonable, opinion to hold at that time. For example, the analytical fulcrum of the write-up is a half-page section titled “Despite Lack of Money and Skills Nation Fights to Avoid Collapse.”

“When Pakistan suddenly received its freedom last Aug. 15, proud and energetic patriots boasted that they had created a nation with more land than France and more people than Germany. Granting these comparisons, Pakistan still lacks most of the attributes of a modern state.”

The section then goes on to indicate how Pakistan was “fighting a close battle with economic bankruptcy” in six key areas: Labor, Food, Raw Materials, Industry, Transportation and Finances. A few of these are reproduced here:

“Labor: Of the approximately 70 million Pakistanis more than 80% are farmers, a very few are wealthy landlords and the rest are shopkeepers and artisans. Nearly all of Pakistan’s financial and professional men were among the approximately four million Hindus who fled to India. From India, Pakistan got about siz million impoverished Moslem peasants who for the most part left their agricultural implements behind. Pakistan has huge transient camps fll of landless farmers and an almost complete lack of skilled technicians or businessmen.”

“Industry: …At present in all of Pakistan there are only 26,000 workers employed in industry. She has no big iron and steel centers, only 34 railway repair shops, no match factories, no jute mills, no paper mills and only 16 cotton mills against India’s 857…”

“Transportation: In all the 370,000 square miles of Pakistan there are only 7,260 miles of railway and only 9,575 miles of paved roads. There are an estimated 53,000 miles of dirt roads and trails… Pakistan has had difficulty in getting enough coal to keep the railways running and even then has had to pay about three times teh normal price per ton In September alone the country lost more than $10 million on railway operations.”

“Finances: Pakistan’s financial troubles are compounded out of her political, trade and industrial failures. At the time of the division Hindu businessmen took out all the gold bullion, jewels and other liquid assets they could carry with them. With normal trade cut off by the rioting and use of railroads for refugees, Pakistan’s income probably will not exceed 450 million rupees for the current year against almost certain expenditures of 800 million. Officials talk hopefully of foreign investment or loans, but in Pakistan’s present condition the risks are not very attractive.”

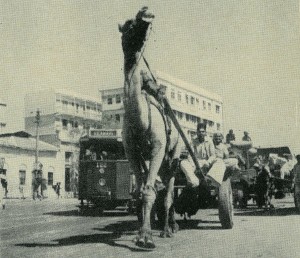

Another picture in the cover-story depicts the realities that this analysis is pointing towards. The caption reads:

Another picture in the cover-story depicts the realities that this analysis is pointing towards. The caption reads:

“ONE CAMEL TOWN” would be a good description of Karachi in terms of world capitals. Although the city has some modern transport, communications are inadequate.”

By way of conclusion, let me just say that I have never believed that being dealt a bad hand at birth is any excuse for all the ways that we have messed up our political and economic affairs since then. Having said that, as I re-read the LIFE issue today, I could not help thinking that the country survived those early years despite all the odds was no mean achievement.

Ms. Margaret Bourke-White was probably not the only one surprised by this fact. Unfortunately, this makes thinking about all the mistakes we have made since then only that much more painful.

Note: Originally posted at ATP on 13 August, 2007.

ASA

I want the 1948 issue of Jan 4, the one displayed on this site. If anyone willing to give it to me, or sell, contact me.

medadabhoy@hotmail.com

Yawn,

Another boredom in verbosity from MJ Akbar.

There is one aspect oj Jinnah that has escaped has escaped this sleuth: how the style of the weave of Jinnah’s socks impacted his daily decisions?

There were days Jinnah wore cross weave and there were days he fancied straight lined.

Please read the entire article.. It says why Nehru rejected Jinnah’s demands..

Jaswant’s Jinnah: Dividing India to save it

By M J Akbar

Two questions frame the Jaswant-Jinnah controversy. Was Jinnah secular? Do Nehru and Patel share the “guilt” for Partition?

Jaswant Singh’s Jinnah has certainly provoked much ado about something, but what is that something? Would this biography have made news if the author had not been a senior leader of the BJP? The world of books requires some chintan, but fortunately no chintan baithak. Who or what, then, is the story: Jinnah or the BJP? The two are not entirely unrelated, for the BJP was formed as a direct consequence of the creation of Pakistan. The umbilical cord still sends spasms up its central nerve.

Two questions frame the Jaswant-Jinnah controversy. Was Jinnah secular? Do Nehru and Patel share the “guilt” for Partition?

Neither question is new, but both have an amazing capacity for reinvention. Jawaharlal’s great socialist contemporary, Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, fired the first broadside in “The Guilty Men of Partition”: the title implied that responsibility extended beyond Jinnah. But since his purpose was polemical, the frisson was lost in forgotten corners of libraries. Jaswant Singh had little to gain from searching for some good interred with Jinnah’s bones, and a bit to lose.

For most of his life, Jinnah was the epitome of European secularism, in contrast to Gandhi’s Indian secularism. Jinnah admired Kemal Ataturk, who separated religion from state. Gandhi believed that politics without religion was immoral; advocated equality of all religions, and even pandered to the Indian’s need for a religious identity. He never publicly disavowed the ‘Mahatma’ attached to his name, even when privately critical, and understood the importance of ‘Pandit’ before Nehru, although Jawaharlal was not particularly religious. Azad had a legitimate right to call himself a Maulana, for he was a scholar of the Holy Book.

Jinnah was not an agnostic. He was born an Ismaili Khoja, and consciously decided to shift, under the influence of an early mentor, Badruddin Tyabji, from the “Sevener” sect, which required obedience to the Aga Khan, to the Twelvers, who recognized no leader. But his faith did not include ritual. He might have posed in a sherwani to demand Pakistan, but he would have considered ‘Maulana Jinnah’ an absurdity. In the end, Jinnah and Gandhi were not as far apart as the record might suggest. Jinnah wanted a secular nation with a Muslim majority; Gandhi desired a secular nation with a Hindu majority. The difference was the geographical arc. Gandhi had an inclusive dream, Jinnah an exclusive one.

The Indian elite tends to measure secularism in pegs: Hindus who do not drink are abstemious, and Muslims who do not are puritan. Jinnah was content with a British lifestyle. He anglicized his name from Jinnahbhai to Jinnah, and dropped an extra ‘l’ from Alli. His monocle was styled on Joseph Chamberlain’s, and he even had a PG Wodehouse moment during a visit to Oxford, when he was arrested for frolics on boat race day (he was let off with a caution; he would never spend a day in jail). His secret student dream was to play Romeo at Old Vic, and only an anguished letter from his father (“Do not be a traitor to your family”) stopped him from becoming a professional actor. He relaxed after a tiring day by reading Shakespeare in a loud resonant voice.

His politics was nationalist and liberal. His early heroes were Phirozeshah Mehta and Dadabhai Naoroji (known as “Mr Narrow-Majority” because he was elected to the House of Commons in 1892 by only three votes). After he met Gopal Krishna Gokhale at his first Congress session in 1904, his “fond ambition”, in Sarojini Naidu’s words, was to become “the Muslim Gokhale”. No one could have hoped for higher praise than what Jinnah received from Ms Naidu: “…the obvious sanity and serenity of his worldly wisdom effectually disguise a shy and splendid idealism which is of the very essence of the man”. Jinnah was only 28.

He scoffed at Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan’s two-nation theory, and wrote an angry letter to The Times of India challenging the legitimacy of the famous Muslim delegation to Lord Minto on October 1, 1906, which built the separatist Muslim platform. (The Times did not print it.) He ignored the convention in Dhaka on December 30, 1906 where the Muslim League was born. Perhaps the best glimpse of Jinnah’s idealism, in my view, is from the memoirs of his friends. The cool Jinnah broke down and cried thrice in public: after sitting, frozen, for five hours at the Khoja cemetery on the day his young wife, Ruttie, was buried; when he was taking the train back from Calcutta in 1928 after the failure of the talks on the (Motilal) Nehru Report; and when he visited a Hindu refugee camp in Karachi in January 1948.

In 1928, he thought he had lost the last chance for Hindu-Muslim unity; and as he watched the stricken Hindus twenty years later, he whispered, “They used to call me Quaid-e-Azam; now they call me Qatil-e-Azam.”

Since Jaswant Singh has written a thematic biography, rather than a comprehensive one, the book skims over personality and addresses the politics of partition. Jinnah’s life is a window through which the author sees the larger landscape of Pakistan, and the heavily mined road towards this green horizon. One of the best sections of the book is the detailed examination of the great debates of 1927 and 1928, although it does underplay the influence of the Hindu Mahasabha on the Congress at the time. What is evident is that Jinnah walked away from 1928 with a deep sense of grievance, and when he returned to politics in 1934, it was with a firm sense of entitlement. From this, emerged, propelled by steely commitment and brilliant leadership, Pakistan in 1947.

The alleged “guilt” of Nehru and Patel is the story of 1946 and 1947, since there were no disputes in the Congress on the unity of India before that. A point needs to be stressed for those who find Nehru-baiting irresistible. Nehru was not the predominant power in the Congress at that time. Not only was Gandhi alive, and deeply involved, but Patel was an equal. He could not impose his personal views upon the Congress, without support, and decisions were made through long and even tortured discussions. The Congress was democratic in spirit and practice. Even after Gandhi’s assassination Nehru faced a strong challenge to his leadership, from Purushottam Das Tandon.

The “guilt” centres around Nehru’s response to the Cabinet Mission Plan in 1946 and the Congress Working Committee resolution on March 8, 1947 accepting “a division of the Punjab into two provinces, so that the predominantly Muslim part may be separated from the predominantly non-Muslim part”. (Nehru had earlier voiced the idea of a trifurcation of Punjab; eventually, that is what happened.)

The Cabinet Mission Plan is now of academic interest since it was overtaken by Partition, but it is true that on June 25, 1946 Congress accepted it in the hope of establishing a “united democratic Indian Federation with a Central authority, which would command respect from the nations of the world, maximum provincial autonomy and equal rights for all men and women in the country”. And on July 10, Nehru, newly elected Congress President, rejected “Grouping”, one of the key (if still opaque) aspects of the Plan. Azad described this, politely, as one of those “unfortunate events which changed the course of history”.

But Nehru was not the dictator of the Congress. Gandhi could have intervened and declared him out of order. The working committee could have convened and reaffirmed its resolution to satisfy Muslim League doubts. The fact that the rest of the Congress was largely (but not completely) silent indicates rethinking. The provisions of the Plan could have left the political map of India an utter horror story, enmeshed by potentially rebellious Princely States, and “Groupings” with their own executives and Constituent Assemblies, buttressed by the right to secede in 10 years. Jinnah might have been content with a “moth-eaten” Pakistan. Nehru would not accept a “moth-eaten” India.

The Punjab resolution of March 1947 was passed in the absence of Gandhi and Azad. Patel and Nehru were its stewards. When Gandhi asked for an explanation, he got an excuse. Patel was disingenuous: “That you had expressed your views against it, we learnt only from the papers. But you are of course entitled to say what you feel right.” Nehru was even more evasive: “About our proposal to divide Punjab, this flows naturally from our previous discussions.” Gandhi and Azad were still adamant that they would not accept Partition: had Nehru and Patel surrendered behind the back of the man who led the independence movement?

The Punjab resolution was prefaced by a conditional phrase: “faced with the killing and brutality that are going on”. By March 1947, Nehru and Patel were more concerned about saving India from the consequences of Pakistan-inspired violence. The experiment in joint Congress-League had begun against the backdrop of the great Calcutta killings, which began with Direct Action Day on August 16, 1946 and never stopped for a year, when Gandhi went on his heroic fast for peace in Calcutta: Gandhi’s supreme courage and conviction have few parallels. This was followed by the gruesome Bihar riots. There was administrative gridlock in Delhi and a drift towards anarchy across the breadth of India. Gandhi did not intervene to revise this CWC resolution either, despite his public reservations. Elsewhere, Azad and Rajendra Prasad have explained what happened. Patel persuaded the Mahatma that the option was either Partition or open war with the Muslim League, which meant a nation-wide civil war. Perhaps only Gandhi believed that Indian unity could have survived the Calcutta riots, and he too wavered.

On April 21, 1947 Nehru said openly that those “who demanded Pakistan could have it”. He entered a caveat: provided they did not coerce others to join such a Pakistan, or indeed to set up separate Stans. Jinnah did his best to partition India further. Nehru and Patel saved India from anarchy by isolating a wound that would have infected the whole of India if it had not been cauterized and sutured. For this they deserve our deepest gratitude. By early May, Nehru was able, in private conversations with Mountbatten in Shimla, to defuse what he saw as nothing short of Balkanization of the subcontinent, the details of which are in my biography of Nehru.

The anarchy that is Pakistan today would have visited India six decades ago. What ironic stupidity that a self-styled admirer of Patel should ban a book that describes how Patel and Nehru overcame, groping through complex imponderables and unimaginable horror, the greatest challenge in modern Indian history.