Centuries old Kelash culture of Kafiristan (also sp. Kalash, Kailash) is at a greater risk today than any time in the past.

Despite their remote location – landlocked in winters – last of the Kelash race is maintaining tenacious hold in district Chitral but is vulnerable to ravages of time and different pressures with external locus. Many have been forced to join the drift to the cities. But when asked what they want, their collective answer is simple: we want our old way of life. Which is why, pastoral Kelash have been able to keep some of their cultural traditions and identity so far.

Despite their remote location – landlocked in winters – last of the Kelash race is maintaining tenacious hold in district Chitral but is vulnerable to ravages of time and different pressures with external locus. Many have been forced to join the drift to the cities. But when asked what they want, their collective answer is simple: we want our old way of life. Which is why, pastoral Kelash have been able to keep some of their cultural traditions and identity so far.

I had the opportunity to explore the larger Kelash valleys and to get to know the people during my two years in the small village Mirkhanni – a gateway to Kalash trilogy: the valleys Rumbor, Bumbret or Birir. One can take a 4 x 4 jeep (or hire one) from Attaliq Bazaar Chitral, or more adventurous type can get off on foot and walk along river Kunar up to Ayun.

I had the opportunity to explore the larger Kelash valleys and to get to know the people during my two years in the small village Mirkhanni – a gateway to Kalash trilogy: the valleys Rumbor, Bumbret or Birir. One can take a 4 x 4 jeep (or hire one) from Attaliq Bazaar Chitral, or more adventurous type can get off on foot and walk along river Kunar up to Ayun.

From Ayun, the road forks left to Bumbret and right to Rumbor. There you will see lush green tree lined terraces, dancing and noisy torrents and lofty snow capped peaks set at a distance in the backdrop of forests of Himalayan. Rumbor is friendliest of all valleys where as Bumbret is most picturesque. The mouth of Birir Valley is at village Gahiret, about seven kilometres south of Ayun. Birir is the most traditional of all valleys and it peters out beyond village Guru. Near the village, you will find out a breathtakingly beautiful spring beneath a mound of stones. It is possible to trek between the valleys.

Some historians and anthropologists think that the Kelash are descendants of Indo-Aryans who overran the region in the second millennium BC. The Kelash say they are from a place called Tsiam, though nobody is sure where that is. Commonly they are considered descendants of Alexander from Macedon who came this way. Their warrior like forebears managed for centuries to keep everyone – including Tamerlane – at bay. In 1893, the British and Afghan governments agreed on a common border that cut right through Kafiristan dividing the community into two parts. Abdur Rahman who was then Amir of Afghanistan renamed Afghan Kafiristan as Nuristan – land of Light.

The Kelash are called Kafirs (infidels) and their land is known as Kafiristan. Between the 13th and 16th centuries the Chitralis gradually subdued the Kelash. By the 19th century, Kelash had been pushed into the higher valleys of the southern Hindu Kush. Rudyard Kipling set his book The Man who would Be King in Kafiristan, portraying the people as fierce and credulous though he never went there. And later, what Geoffrey Moorhouse has described in his book To the Frontier is no more there.

The Kelash are called Kafirs (infidels) and their land is known as Kafiristan. Between the 13th and 16th centuries the Chitralis gradually subdued the Kelash. By the 19th century, Kelash had been pushed into the higher valleys of the southern Hindu Kush. Rudyard Kipling set his book The Man who would Be King in Kafiristan, portraying the people as fierce and credulous though he never went there. And later, what Geoffrey Moorhouse has described in his book To the Frontier is no more there.

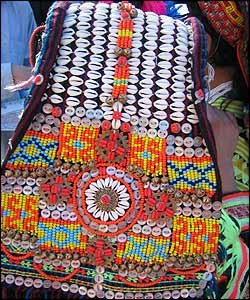

Lively by nature, the Kelash are Mediterranean looking. Men have largely traded traditional goat skin tunics for Shalwar Qamiz and Chirtali caps, often with plumes, feathers, or fresh flowers in the brim. It is the dress of the women that is unique and quite amazing. Even in the fields, women wear immense black or brown dresses reaching to the ground, bound at the waist with a sash. Over locks of hair they wear splendid headpieces decorated with cowries, shells, beads, buttons, coins and plumes. The formal forms of these outfits are spectacular, with embroidery, mounds of bead necklaces and bells. They often decorate their faces with mulberry juice tattoos or pomegranate seeds or blacken them with burnt goat’s horn (also for sunburn protection). I once saw a three years old child completely coated with the soot of burnt horns. A local told, “This will keep the baby fair coloured through out life.”

The Kelash religion is complex and polytheistic with a single creator, called Dezau or Khodai, and many other lesser gods and spirits, each with its own responsibilities. Two important ones are the warrior god Mahandeo, guardian of crops, animals, other public matters, and the female goddess Jestak who cares for home, family and private matters. All need occasional compensations, usually in the form of goat sacrifices and ceremonies at their shrines scattered through the valleys. The religious traditions are taught by one generation to the

next.

Traditionally the dead are not buried. The wooden coffins used to be placed on the ground. Wooden totes or effigies were carved for wealthy or honoured people. Totems are scarce now; some carted off by anthropologists and treasure hunters. These days the dead are simply placed on cart in the graveyard.

Tradition has it that women are less pure than men are and there are precise rules about what each may do, where they may go and how to purify people and places. Women during menstruation or childbirth are confined to a lodge called Bashaleni (which is also a shrine to the goddess Dezalik, who looks after births). Men cannot go in; even other women must be ‘purified’ after a visit. In old days, even food could be served to the women confined in Bashaleni only by virgin boys, untouched by women. Gradually these traditions are losing their power. But still it is the women that are seen working around in fields or homes and men spend all their quality time sitting on the pathways. The burden of perpetuating the last strains of Kelash culture is also born by women alone.

The Kelash take their festivals seriously. In addition to religious ceremonies there is always dancing and local made wine. Typically the older men stand in the centre, taking turns chanting old legends. Accompanied by drums the women dance round them arms around one another’s waists and shoulders in spinning twos and threes or trance like encircling lines.

The Kelash take their festivals seriously. In addition to religious ceremonies there is always dancing and local made wine. Typically the older men stand in the centre, taking turns chanting old legends. Accompanied by drums the women dance round them arms around one another’s waists and shoulders in spinning twos and threes or trance like encircling lines.

There may be day dancing (adua-naat) and night dancing (raadt-naat), or both. Each valley has its own style and timing. The dates may not be fixed until the last minute, often depending on harvest or other work, so you could end up waiting days or even weeks for the kick off. Locals from down country may find it difficult to attend any such function but foreigners are often welcome.

This feast dedicated to spring and to future harvests is called Joshi. It includes day dancing and family reunions for four to six days in mid May. The summer festival Uchau, celebrating the wheat and barley harvests, is a big tourist draw. It may include night dancing every few days in successive villages, form mid June to mid August. Pul is held only in Birir, for three or four days in late September or early October. Night dancing is held in various villages and day dancing on the last day. It marks the walnut and grape harvests and the end of wine making, though its origins concern the return of shepherds from the high pastures. This solstice festival called Chaumos is probably the biggest for the Kelash, with visiting, feasting and night dancing for around 10 days starting in mid December.

Kelash boasts of a truly unique culture. One that is under threat from the forces of modernity. It is perhaps the sole claim to fame for the region besides gorgeous natural beauty, poverty and its remoteness.

S A J Shirazi is a Lahore (Pakistan) based writer. (See more at Shirazi’s blog ‘Light Within’). All images are from Flickr.com.

The Kalash as the Native people of Chitral should be given the status of first people .There culture and history need to be tought in local schools,the Chitral Government should fund the building of a Kalash Temple , as well as paying for the upkeep of existing kalash shrines ect.All hotels and tourist projects should be in Kalash hands, land issues with Muslems must be settled justly.Kalash children should not have to learn Islam at school,Kalash children need to learn Kalash Religion only,the government should set up a Kalash cultural centre were kalash art like carving could be revived.The Kalash region should be given autonomy and local government with kalash police not muslems, to ensure an end to Muslem imperialism .