Adil Najam

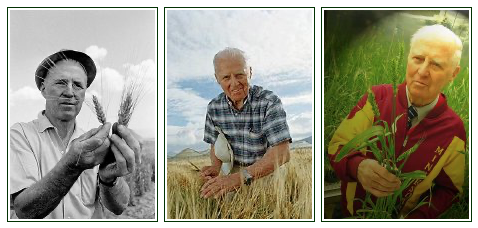

Norman Borlaug, winner of the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize and father of the ‘Green Revolution‘, including in Pakistan, died in Texas at age 95. Few in Pakistan have ever heard his name, but no one has had a deeper impact, for good as well as bad, on agriculture in Pakistan as we know it today than Dr. Norman Borlaug.

In reporting Dr. Borlaug’s death, Dallas News writes:

In reporting Dr. Borlaug’s death, Dallas News writes:

The Nobel committee honored Dr. Borlaug in 1970 for his contributions to high-yield crop varieties and bringing agricultural innovations to the developing world. Many experts credit the green revolution with averting global famine during the second half of the 20th century and saving perhaps 1 billion lives. “More than any other single person of his age, he has helped to provide bread for a hungry world,” Nobel Peace Prize committee chairman Aase Lionaes said in presenting the award to Dr. Borlaug. “We have made this choice in the hope that providing bread will also give the world peace.”

The Los Angeles Times adds:

Borlaug was one of only five people in history to score the trifecta of winning the Nobel Peace Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal — placing him in the company of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela and Elie Wiesel. He was also named by Time magazine in 1999 as one of the 100 most influential minds of the 20th century.

Despite all this, he has been amongst the least well known winners of the Nobel Peace Prize ever, even in his native USA. But given the totally transformative impact that the green revolution had on agrarian Pakistan it is even more sad that so few Pakistanis even know who he was or just how and how much he effected their lives.

To understand just how important he was in shaping agriculture in Pakistan – no, it was not Ayub Khan, it was Norman Borlaug who shaped it – a reading Gregg Easterbrook’s 1997 profile of Norman Borlaug is instructive. It is recommended that you read the full profile, but here are some specially telling excerpts:

He received the Nobel in 1970, primarily for his work in reversing the food shortages that haunted India and Pakistan in the 1960s. Perhaps more than anyone else, Borlaug is responsible for the fact that throughout the postwar era, except in sub-Saharan Africa, global food production has expanded faster than the human population, averting the mass starvations that were widely predicted… The form of agriculture that Borlaug preaches may have prevented a billion deaths.

Entering college as the Depression began, Borlaug worked for a time in the Northeastern Forestry Service, often with men from the Civilian Conservation Corps, occasionally dropping out of school to earn money to finish his degree in forest management. He passed the civil-service exam and was accepted into the Forest Service, but the job fell through. He then began to pursue a graduate degree in plant pathology. During his studies he did a research project on the movement of spores of rust, a class of fungus that plagues many crops… He decided that his life’s work would be to spread the benefits of high-yield farming to the many nations where crop failures as awful as those in the Dust Bowl were regular facts of life.

In 1943 the Rockefeller Foundation established the precursor to CIMMYT to assist the poor farmers of Mexico, doing so at the behest of the former Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, of the Pioneer Hi-Bred seed company family, who had been unable to extract any money from Congress for agricultural aid to Mexico. Soon Borlaug was in Mexico as the director of the wheat program — a job for which there was little competition, backwater Mexico in the 1940s not being an eagerly sought-after posting. Except for brief intervals, he has lived in the developing world since. The program’s initial goal was to teach Mexican farmers new farming ideas, but Borlaug soon had the institution seeking agricultural innovations. One was “shuttle breeding,” a technique for speeding up the movement of disease immunity between strains of crops. Borlaug also developed cereals that were insensitive to the number of hours of light in a day, and could therefore be grown in many climates.

Borlaug’s leading research achievement was to hasten the perfection of dwarf spring wheat. Though it is conventionally assumed that farmers want a tall, impressive-looking harvest, in fact shrinking wheat and other crops has often proved beneficial. Bred for short stalks, plants expend less energy on growing inedible column sections and more on growing valuable grain. Stout, short-stalked wheat also neatly supports its kernels, whereas tall-stalked wheat may bend over at maturity, complicating reaping. Nature has favored genes for tall stalks, because in nature plants must compete for access to sunlight. In high-yield agriculture equally short-stalked plants will receive equal sunlight. As Borlaug labored to perfect his wheat, researchers were seeking dwarf strains of rice at the International Rice Research Institute, in the Philippines, another of the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations’ creations, and at China’s Hunan Rice Research Institute.

Once the Rockefeller’s Mexican program was producing high-yield dwarf wheat for Mexico, Borlaug began to argue that India and other nations should switch to cereal crops. The proposition was controversial then and remains so today, some environmental commentators asserting that farmers in the developing world should grow indigenous crops (lentils in India, cassava in Africa) rather than the grains favored in the West. Borlaug’s argument was simply that since no one had yet perfected high-yield strains of indigenous plants (high-yield cassava has only recently been available), CIMMYT wheat would produce the most food calories for the developing world. Borlaug particularly favored wheat because it grows in nearly all environments and requires relatively little pesticide, having an innate resistance to insects…

In 1963 the Rockefeller Foundation and the government of Mexico established CIMMYT, as an outgrowth of their original program, and sent Borlaug to Pakistan and India, which were then descending into famine. He failed in his initial efforts to persuade the parastatal seed and grain monopolies that those countries had established after independence to switch to high-yield crop strains.

Despite the institutional resistance Borlaug stayed in Pakistan and India, tirelessly repeating himself. By 1965 famine on the subcontinent was so bad that governments made a commitment to dwarf wheat. Borlaug arranged for a convoy of thirty-five trucks to carry high-yield seeds from CIMMYT to a Los Angeles dock for shipment. The convoy was held up by the Mexican police, blocked by U.S. border agents attempting to enforce a ban on seed importation, and then stopped by the National Guard when the Watts riot prevented access to the L.A. harbor. Finally the seed ship sailed. Borlaug says, “I went to bed thinking the problem was at last solved, and woke up to the news that war had broken out between India and Pakistan.”

Nevertheless, Borlaug and many local scientists who were his former trainees in Mexico planted the first crop of dwarf wheat on the subcontinent, sometimes working within sight of artillery flashes. Sowed late, that crop germinated poorly, yet yields still rose 70 percent... Owing to wartime emergency, Borlaug was given the go-ahead to circumvent the parastatals. “Within a few hours of that decision I had all the seed contracts signed and a much larger planting effort in place,” he says. “If it hadn’t been for the war, I might never have been given true freedom to test these ideas.” The next harvest “was beautiful, a 98 percent improvement.” By 1968 Pakistan was self-sufficient in wheat production. India required only a few years longer.

Of course, the green revolution – and Normal Borlaug – are not without controversy. Many, including myself, have argued that the architects of the green revolution were so fixated on yields that they underestimated its social and ecological consequences. In recent years, there have also been concerns about Dr. Borlaug’s unconditional advocacy of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). There is much that can and should be debated about the impacts of the green revolution. But what is beyond debate is that Pakistan agriculture post-Norman Borlaug was a radically different reality than Pakistan agriculture pre-Norman Borlaug.

Of course, there were many in the Pakistan agriculture establishment who took it from there and without whom things would never have moved on, but Borlaug’s impact was pivotal – as had been the impact of the late Roger Revelle on Pakistan’s irrigation system. This is not to take away credit from all the others, but it is to give credit due to him.

Legitimate debates on the green revolution notwithstanding – and for those of us who work on these issues, these debates must continue – no one can doubt Dr. Borlaug’s deep commitment and single-minded efforts for eradicating world hunger and the phenomenal impact of the green revolution across the globe, but especially in South Asia. In the years since its creation, few people have changed the lives of as many Pakistanis as deeply as he did and are as unknown by those they impacted as Dr. Norman Borlaug.

Thank you for this writeup. It is great to see you raise issues and people who we all have forgotten. Keep it up ATP.

Great post ATP.

You are an educational site.

I also did not know about him and am glad that I read through all of this and learnt much.

Thanks.