Adil Najam

Pakistanis have gotten used to feeling unsafe and afraid. Today they are feeling even more unsafe and afraid. And that is no accident.

Afraid and unsafe is exactly how the butchers who tortured and then murdered Syed Saleem Shahzad want us to feel.

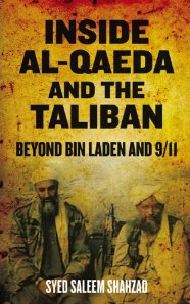

Those who brutally murdered journalist, and author of the recent book Inside Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, Syed Saleem Shahzad clearly wanted to silence him. But the calculated and staged ‘delivery’ of his murdered body was meant to do more than just silence a journalist. It was an attempt to silence a society.

The message to Saleem Shahzad was cold and bloody and brutal. The message to Pakistanis – and not just journalists, but all who may dare to ‘speak up’ – was equally cold and bloody and brutal. Of course, nothing can compare to the fatal, ultimate and irreversible wounds that were inflicted on Saleem Shahzad. But the chill that ran down the spine of all Pakistanis was also real. Let us not doubt for a moment that this was a calculated act. That this chill is exactly what his murderers wanted to deliver.

The message to Saleem Shahzad was cold and bloody and brutal. The message to Pakistanis – and not just journalists, but all who may dare to ‘speak up’ – was equally cold and bloody and brutal. Of course, nothing can compare to the fatal, ultimate and irreversible wounds that were inflicted on Saleem Shahzad. But the chill that ran down the spine of all Pakistanis was also real. Let us not doubt for a moment that this was a calculated act. That this chill is exactly what his murderers wanted to deliver.

Murder, as an article in Dawn pointed out, is “the severest form of censorship” on he who is murdered. But it is also the most chilling of messaging for all others. What was delivered to Pakistanis today was not just the dead body of a journalist, but the proverbial “horse’s head” (as in The Godfather) – a promise to impose censorship “by all means necessary.”

The article in Dawn, by Adnan Rehmat, makes for chilling reading itself:

… Syed Saleem Shahzad has joined the unacceptably long list of over 70 journalists who have been killed in the line of duty in Pakistan since 2000. How has Pakistan become the most dangerous country to practice journalism?

… The violence that has engulfed Pakistan for the last decade did not leave the media immune to its consequences. While there have been journalists who have been killed in bomb blasts in markets, processions and funerals across the country, caught in the wrong place and wrong time, the last three years have seen a rise against target killings of journalists in Pakistan. At least 17 have been killed this way.

The number of journalists who were target-killed grew sharply after the media stopped self-censoring themselves too much in the wake of the footage of a girl being flogged by the Taliban in Swat, which proved a turning point in the media losing its fear of the Taliban. This was the beginning of a more unrestrained narrative on terrorism which injected grim realism in reporting. The consequence of the media finding that the public was receptive to this kind of reporting promoted a culture of risk taking which first generated warnings from the Taliban to the media to “behave.” When there was no major change in the behavior and attitude of the media, the killings began.

… While over 70 have been killed, a staggering 2,000-plus have been injured, arrested or kidnapped – a large number of them by the military regime of General Pervez Musharraf. But while the militants had been hounding and hurting the journalists since 2002, the “Musharraf treatment” added a new dimension to the policy of intolerance for media openness and pluralisms. In one single instance nearly 120 journalists were arrested in Karachi in one fell swoop and in another single incident about 140 in Islamabad by Musharraf’s thugs. It is this state sanction for this kind of intolerance of media independence that has now allowed the level of impunity where many journalists have been killed with the suspicion for most falling on the security establishment.

The fact that the killers of not even one Pakistani journalist killed has been found, prosecuted and punished has meant the media has been an easy target.

Saleem’s death is not ordinary even among the long list of journalists killed in Pakistan in recent years. Because his last news story attempted to establish that the security establishment had been in talks with al Qaeda to negotiate a deal that would prevent attacks on it, it is reasonable to assume that this claim was linked with his kidnap, torture and murder. He had told a friend a day after the report was published that this was just the tip of the proverbial iceberg and that he would be filing a couple of major stories that would rattle many.

Whether it was the security establishment that killed him or the declared terrorists, the fact is he was killed for daring to attempt to share information that affected the country and its people… Saleem’s death signals that dirty secrets will not easily be allowed to be shared with the people of Pakistan.

Details in the accompanying news report in Dawn add even more chilling details to this context:

It was confirmed by the capital police as well as its counterparts in Mandi Bahauddin that a body buried in a local graveyard at Mandi Bahauddin was suspected to be that of (Saleem) Shahzad, an Islamabad-based journalist who had gone missing from the capital on Sunday evening. He had disappeared en route to a news channel’s office in Sector F-6 from his house in F-8/4.

Shahzad, who was the bureau chief for the Hong Kong-based Asia Times, an online publication, and the Italian news agency Adnkronos (AKI) and had worked for the Dawn Media Group’s evening newspaper Star for over a decade, was known for his investigative reporting on militancy and Al Qaeda. He had moved to Islamabad after Star closed down in 2007. His book, “Inside Al-Qaeda & the Taliban: Beyond Bin Laden and 9/11”, had recently been published.

After his disappearance, the Human Rights Watch alleged that Shahzad had been picked up by the ISI and that the intelligence agency had threatened him last year as well when he had reported on the quiet release of Mullah Baradar, an aide to Mullah Omar, who had been captured by Pakistan earlier. Ali Dayan, Pakistan researcher for HRW, also made public an email that Shahzad had sent then with the instructions to make it public in case something happened to him. The email provided Shahzad’s account of a meeting he held with two ISI officials on October 17, 2010. After he disappeared on Sunday, there were allegations that he had been picked up by the ISI because of his recent story on the PNS Mehran base attack. Shahzad had reported that the attack took place after the Navy identified and interrogated a few of its lower-level officers for their ties with Al Qaeda.

… On Tuesday it came to light that the body found at Head Rasul a day earlier was of the missing journalist. He was identified from the photos taken of the corpse on Tuesday during the postmortem at District Headquarters Hospital Mandi Bahauddin. The police force’s efficiency knew no bounds on Tuesday. First the police force of Sara-i-Alamgir found an abandoned Toyota Corolla, which belonged to Shahzad, near the Upper Jhelum Canal. The vehicle, which had gone missing along with the journalist, had a broken window and a damaged ignition switch, hinting at car theft. The police also found two CNICs and press cards, as well as other documents pertaining to Shahzad. They then contacted the Margalla police in Islamabad.

Once the police from Islamabad examined the car and determined its owner’s identity, they were informed by their counterparts that the Mandi Bahauddin police had found a body a day earlier. According to the details collected by Dawn, some passersby spotted a corpse in the water on Monday. The Head Rasul police shifted the body to the DHQ. Unusually quickly for Pakistani police, all legal formalities were completed, the autopsy was conducted on the unidentified body and it was handed over to Edhi Centre for burial. It was interred at the local graveyard temporarily.

According to the police, the postmortem report said that Shahzad had been subjected to severe torture. The report said he had 15 major injuries including fractured ribs and deep wounds on the abdomen. It was also evident that the journalist’s hands and feet had been tied as there were marks on his wrists and ankles. However, his hands and feet were not tied when he was found. The police said that the victim had been killed in the early hours of Monday.

The Mandi Bahauddin police told the capital police that there was no mortuary at the DHQ and Edhi Centre to keep the body; hence the pace at which it was buried. The family, which was contacted by the capital police, identified him from the photographs, clothes and cards. Shahzad leaves behind a widow and three children.

There is little that one can add to these descriptions. And it seems hallow to simply say that we should refuse to feel unsafe and afraid. How else can one possibly feel today?

Except that there is that other horrible truth staring us in the face today. A truth that Syed Saleem Shahzad – who himself must have felt far more unsafe and afraid than any of us can possibly feel – was no doubt aware of and probably acted upon: Feeling unsafe and afraid is no cure for feeling unsafe and afraid. It leads only to an even greater insecurity and fear.

171703 152183Looking ahead to look you. 500281

xeueaptar enrcg fwxlgih eekr hqpjesobkgoragh

May Allah bless us

A sad incident and recently another journalist (in Gujrat area) has a painful story put before media….