Syed Abbas Raza

A military dictatorship is a military dictatorship, and a democracy is a democracy. And the latter is always automatically better than the former. It is safer to agree with this statement and to look at every particular complex political situation through the lens of this cliché than to risk having one’s liberal-democratic credentials questioned.

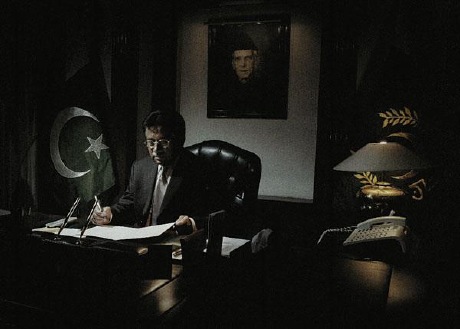

But as a friend of mine once remarked, “All arguments for democracy in Pakistan are theoretical. For dictatorships, the greatest argument is the actual experience of Pakistani democracies.” Very similarly, another friend recently commented that “There are of course no theoretical arguments for a dictatorship, only practical ones.” In the case of Pakistan, the last two civilian democratic governments were sham democracies, and while I by no means support everything Pervez Musharraf has done, especially recently, there are various things for which his government deserves praise. Moreover, while George W. Bush may have gotten almost everything else wrong, his Pakistan policy has been basically sound.

Whenever Musharraf’s name comes up in the Western media, it is inevitably followed by an appositive whisper like “…who took power in a military coup in 1999.” It is never mentioned that the coup was thrust upon him by the greatest kleptocrat in Pakistan’s history, and then serving Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, who tried to kill Musharraf by refusing to allow his plane to land in Karachi when Musharraf was returning from an official trip to Sri Lanka as Pakistan’s military chief. (Sharif wanted to promote and appoint one of his lackeys as the chief of the army, bypassing many more-senior officers, and Musharraf’s term was not yet up.) With over 200 civilians on board the commercial PIA jumbo flight, and with little fuel to spare, Musharraf himself entered the cockpit and radioed down to the army corps commander in Karachi. He ordered that the airport be secured, that the fire trucks preventing the plane from landing be immediately removed from the runway, and that the Prime Minister be arrested. The plane landed with seven minutes of fuel to spare. (All this information can be checked against the testimony of the crew and transcripts of the air traffic communications which were used as evidence in Nawaz Sharif’s subsequent trial.)

At that time, Pakistan stood at the brink of political and economic disaster. Years of mismanagement and outright pillage (friends in the money-management industry in New York tell me that by the late ’90s Pakistan was the largest source of “flight capital”—stolen money which is deposited in secret accounts offshore and managed from New York by American financial experts—in the world) by the supposedly business-friendly Sharif and his cronies had left the State Bank of Pakistan with foreign exchange reserves of a few hundred million dollars. Defaults on international debt payments were imminent. The democratic process itself had collapsed into a travesty in which Sharif had goons from his party scale the walls of the Supreme Court (literally!) and beat the Chief Justice and other judges into submission with clubs. Members of the National Assembly (MNAs) of all parties were being bought and sold like pork futures, switching parties on a weekly basis. Sectarian violence was epidemic, crime was at an all-time high, and religious extremists were gaining ground. In a 1998 survey, Pakistan was identified as the eleventh most corrupt nation in the world, sitting uncomfortably between Latvia and Cameroon. All this in the nuclear-armed, sixth-largest country of the world.

Thus, in this precarious situation in late 1999, the only “democratic” option was to hand over the government to another disastrous criminal gang, and this was not a politically responsible choice. Musharraf knew that what was immediately necessary was the stabilization of the country, and most importantly the economy. He sought the best and brightest Pakistani financial minds from all over the world to undo the damage wrought by the incompetence and robbery by Sharif’s (and that of his predecessor, Benazir Bhutto’s) relatives and cronies.

Shaukat Aziz was the third-most-senior man at Citigroup at the time and a known financial whiz. Musharraf convinced him to come home from NYC at immense cost in personal income to take over as Finance Minister. (Sandy Weil, legendary long-time CEO of Citigroup, lamented that “Pakistan’s gain is our loss.”) Razzaq Daud, a very well-respected industrialist known for his integrity as well as his financial acumen, was made Minister of Commerce, and Dr. Ishrat Husain, serving as Chief Economist at the World Bank at the time, was convinced to return as Governor of the State Bank. By 2002, Pakistan’s foreign currency reserves had risen from a few hundred million to $8.5 billion. That year, Business Week declared the Karachi Stock Exchange the “Best Performing Stock Market of the World.” By the time I visited Pakistan in the autumn of 2004, the change was obvious in the pulsing streets and overflowing markets of Karachi. By October of 2007, Pakistan’s foreign currency reserves had risen to $16.5 billion. The World Bank’s website states that:

After a decade of anemic economic growth, Pakistan’s economy has grown by more than 6.5 percent per year since 2003. While income inequality has increased somewhat, poverty has declined significantly. Exports (in US$ terms) have grown by over 15 percent since 2004. Investment as a share of GDP increased from 17 percent in 2001/02 to 20 percent in 2005/06. A wide-ranging program of economic reforms launched in 2000 [by the Musharraf government, immediately after taking control]—fiscal adjustment, privatization of energy, telecommunications, and production, banking sector reform and trade reform—have played a key role in the country’s economic recovery.

The same people who decry increased American aid to Pakistan after 9/11/01 and (correctly) claim that it mainly goes to the military, are, in their eagerness to discredit both Musharraf’s government and Bush’s foreign policy, quick to explain Pakistan’s recent economic success as a result of that increase in aid. Almost all economists I have spoken to agree that American aid had little or nothing to do with it.

To confront the endemic and systemic corruption in the country, Musharraf set up the National Accountability Bureau (yes, it makes for an unfortunate acronym) to investigate charges against various bureaucrats and others, and put the incorruptible Lt. General Syed Tanweer Naqvi at its head. In addition, he assigned army personnel to be present in civilian government offices where the public could previously not obtain service without paying huge bribes. The presence of army personnel made significant improvements in many cases. When I visited in 2004, a friend showed off his new driver’s license to me. But you’ve been driving for years, I said. Yes, he replied, but it used to be easier to pay off the cops if they stopped you than to pay the exorbitant bribes at the Motor Vehicle Department (or whatever the equivalent office is in Pakistan—I forget). Soon after taking power in 1999, Musharraf also declared all his (very modest) assets and ordered all senior officials in his government to do the same, in the interest of transparency. If any of them is now found to own a condo in Dubai or a chalet in Switzerland, it makes it that much easier to prosecute. This was an unprecedented step in Pakistan. By 2007, it was ranked the 38th most corrupt country in the world – still depressing but much improved.

Musharraf also realized that, as a precondition to genuine democracy, there must be more than lip service to a free press. He started granting unprecedented licenses for new radio and television channels, many of which immediately took a radically anti-government line. In the years since he took over, and until the ill-advised emergency declared by him late last year, every single day one could read the most excoriating editorials against Musharraf in countless Urdu and English newspapers all over Pakistan. His has been an era of more press freedom than ever before in the entire history of Pakistan.

On the religious extremism front, Musharraf has had mixed success. His government failed to follow through with a policy of dismantling madrassas which did not integrate a proper educational curriculum and which are basically training grounds for fundamental jihadists, and illegal mosques which continue to spring up like weeds all over the country. Because of Bush’s disastrous invasion of Iraq, Musharraf had to deal with an increasingly anti-American public, and one which, especially in the provinces bordering on Afghanistan, was increasingly inclining toward the fundamentalist parties. He had to tread lightly or risk civil war. Despite this, he purged the army’s general staff of fundamentalist sympathizers, and Pakistan has captured more terrorists in the war against al-Qaida than all other countries of the world combined. Pakistan has paid a high price for this: weekly, if not daily, suicide bombings by al-Qaida have become the norm, including two assassination attempts against Musharraf himself (which he escaped narrowly) and the recent tragic assassination of Benazir Bhutto.

It is for all of these many reasons that until recently, when he started making disastrously bad decisions in the hopes of staying in a position of power to which, alas, like so many others, he has become addicted, he was a relatively popular leader in most segments of Pakistani society. Business loved him, young people enjoyed the new media and the opportunities the much-better economy was affording them, and middle-class Pakistanis were glad they were not getting shafted by the feudal and business elites. People had seen real improvements in their quality of life under his tenure. In 2002, most people that I know happily voted for him in the referendum that made him president for the next five years. Only religious extremists and people associated with Nawaz Sharif’s party hated him since the teats of patronage and graft that they had become used to suckling on had gone dry under Musharraf. Even Benazir Bhutto at the end was willing to work with him and cut a power-sharing deal because she knew that he represented the only honest and moderate force in the country.

Let us now turn to US policy. It has become common in left-liberal circles in the US to lump Bush’s policy toward Pakistan in with every other catastrophe for which Bush actually is responsible. But it is not clear what the Bush administration could have done differently. The implication that it is American aid which has kept democracy from being restored in Pakistan is ludicrous. First of all, the amount of aid is relatively tiny, and it was in America’s as well as Pakistan’s interest to battle al-Qaida in Afghanistan. Pakistan needed help with money and military equipment for this effort. If anything, the US did not provide enough support, and the State Department always dragged its feet in approving Pakistani requests, such as for helicopters to patrol the border region with Afghanistan. Consider that the total amount of aid delivered to Pakistan since 2001 is less than what Israel gets every year from the United States to illegally expand its settlements on Palestinian land, build its walls and launch its invasions, and less than what the US spends on its disastrous occupation of Iraq every month. Had some of this money been used for reconstruction in Afghanistan (as was promised after the Taliban were removed) it would have gone a long way toward curbing anti-Americanism in Muslim countries.

Pakistani support for the Taliban started under Benazir Bhutto’s civilian government and ended with Musharraf. To whatever degree US policy is responsible for the creation of terrorist training grounds in Afghanistan it is not Bush who is responsible. Those policies were put in place by Ronald Reagan to combat the Soviet Union and continued through the ’90s, by which time the mujahedin had turned against America. Bush was also correct to give Musharraf help and technology in developing safeguards for Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal.

It is entirely fitting that the very conditions that Musharraf has attempted to create to make true democracy possible in Pakistan should provide the force that may remove him from office when he starts to behave autocratically. His granting of unprecedented independence to the judiciary could not be rolled back, as Musharraf found out when he fired the Chief Justice. The press attacked him mercilessly, and lawyers took to the streets. And the fair elections held under his government in February have resulted in a huge loss for Musharraf’s party. The two main opposition parties have recently announced that they will form a coalition, and they will reinstate the judges removed under Musharraf’s emergency rule of a few months ago. They may also impeach Musharraf. This is as it should be, and an ironic measure of Musharraf’s success in strengthening the democratic infrastructure of Pakistan. Perhaps we now have a chance at genuine democracy instead of the rotten-to-the-core one that Musharraf replaced.

It is entirely fitting that the very conditions that Musharraf has attempted to create to make true democracy possible in Pakistan should provide the force that may remove him from office when he starts to behave autocratically. His granting of unprecedented independence to the judiciary could not be rolled back, as Musharraf found out when he fired the Chief Justice. The press attacked him mercilessly, and lawyers took to the streets. And the fair elections held under his government in February have resulted in a huge loss for Musharraf’s party. The two main opposition parties have recently announced that they will form a coalition, and they will reinstate the judges removed under Musharraf’s emergency rule of a few months ago. They may also impeach Musharraf. This is as it should be, and an ironic measure of Musharraf’s success in strengthening the democratic infrastructure of Pakistan. Perhaps we now have a chance at genuine democracy instead of the rotten-to-the-core one that Musharraf replaced.

Syed Abbas Raza is the editor of 3QuarksDaily (3QD). This was originally published in N+1 in response to an article titled “The Back Room President” in N+1.

People say in 2010(Musharraf Tere yaad aai tere jane k baad)

— And as of now,Musharraf reversed everything what he did in 1999 of his own choosing and making.

Naseer

Abbas, I really liked this blog post of yours and I agree totally with the fact that Musharraf did a lot of good for the country. Though in his eagerness to stay in power he did mess up it up in the end and as they history is nothing but the view and opinion of the winner and Musharraf will live as the dictator who wouldnt let go.

To people who have started abusing the author of the post. Everybody is entitled to express their opinions and that is the basis of any democracy. We should be willing to hear the other side as well with objectivity and not get emotional about it.

As for the whole idea of dictatorship, my two cents says that evey country in the world was a dictatorship in the begining and its only once the population of that country started becoming prosperous and educated did the democratic reforms took place. Why is that we, pakistani, have become so sensitive about democracy, independence of judicary and media. Cause under that dictator we had a chance to regroup, get educated and become economically stable and finally found our voice.

Always be optimistic about the future, hopefully the newfound freedom on media, expression and judiciary will herald a new era. Inshallah

Fida Khan

You are right,Pakistan has suffered most at the hands of its so called educated.The author of this blog is trying to justify the unjustifiable.

I have lost all respect for 3QD.

Actually, the word load shedding entered into Pakistani vocabulary in the 1980s (you know who was ruling then. Merde …). But in the 1990s we had surplus electricity and we were even thinking of exporting electricity to India (remember?). However, from the year 2000 onwards we kept beating the dead horse of Kalabagh but did not generate a single megawatt of additional electricity. The result is before us today — but it is too difficult to see because it is darkness all around.