Adil Najam

Our friend Babar Bhatti reports on his blog State of Telecom Industry in Pakistan that in 2007 the total number of mobile subscribers in Pakistan reached 76.6 million. He is reporting from an interesting statistical compilation of achievements compiled by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA); (more number from this report are included below).

Our friend Babar Bhatti reports on his blog State of Telecom Industry in Pakistan that in 2007 the total number of mobile subscribers in Pakistan reached 76.6 million. He is reporting from an interesting statistical compilation of achievements compiled by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA); (more number from this report are included below).

I ask the questions I do in the headline not out of cynicism but out of very honest inquisitiveness. I deal a lot with development related statistics in my professional work and for many reasons the number seems rather surprising to me. It probably is that the meaning of “subscriber” here is different from what I would have expected or that I am unfamiliar with the specifics of how this number is calculated and what it signifies. If so, I am eager to learn. I also wonder to what extent massive growth in mobile phone subscribers is necessarily good for a developing country like Pakistan?

Depending on who you want to believe the population of Pakistan is somewhere around 165-140 million. Probably closer to the latter number; some estimates would suggest even higher. If “subscriber” means the number of unique individuals who are subscribing to a mobile service (as it would in many other development contexts) it would mean that nearly half of all Pakistanis – man, woman, child, old, young, infant, newborn – are mobile phone subscribers.

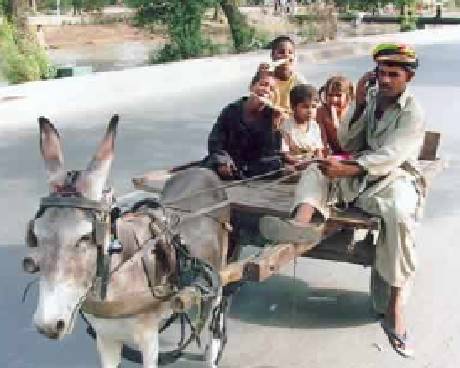

Although anyone in Pakistan knows that the penetration of cellphone to all classes – including middle and lower-middle income groups – is very high, the absolute poor (and there are still a very large number) are not likely to be subscribers. It is also likely that the penetration is much less in rural areas than in urban, that it is much much less amongst the very old and should be zero or nearly zero amongst the very young. I have seen some kids (12-15 years) with cell phone of their own, but these would be mostly in the higher economic strata and it could not be a very high number. Similarly, while the phenomenon of multiple phones per family is now dominant in many middle and most higher income groups, one assumes that it is less prevalent in the lower income groups.

Any set of reasonable assumptions about these are related variables would suggest that the wording from the PTC is potentially misleading. It is more likely that the number is really of the cell phone “numbers” issued and technically in use. The fact, however, is that many many of these “issued” numbers would not really be in use. However, given the “SIM culture” and the rather common practice of holding multiple SIM cards and numbers (I have two myself, and I don’t even live in Pakistan!) it would not be surprising that the real “subscribers” are much less – although a still impressive number.

But that is my second, and more important question. Should we be really be impressed – in a development perspective – if the number of mobile subscribers are high in a developing country? It certainly signifies good business for the industry, but what does it say about the country and national development?

There are those who argue in the literature that the rapid growth of such services in developing countries signifies the failure of governments in providing essential infrastructure. This argument is far more valid in the water sector. A very high number of urban Pakistanis, including very poor ones in katchi abadis buy water from non-municipal sources (private tankers, tubewells, etc.). This does not signify a high private demand for water services as much as it signifies low government provision of the service. The same is true for energy – both in terms of the number of people (even in middle income groups) who have to expend money on private generators or other sources and also those who have to buy fuel wood. At least in the essential services category (cell phones are not really there) this means that significant portions of one’s income have to be spent on buying essential services (at higher prices; e.g., in the water and energy sectors). The poorer you are, the lower your disposable income, and the greater the proportion of that income being spent on these services, which you have to buy privately because the public provision is inconsistent or non-existent.

This is not without relevance to the cellphone situation. For my parents and many others I know, the cell phone is as much a means of security – in an increasingly insecure time – as a means of communication. This is true elsewhere too, but it is even more true in Pakistan. Similarly, the “need” for cellphone increases as other means of communication become unpredictable. E.g., the land-line system. There is also, always, the issue of improper marketing and the consumer being forced into spending much more than they should or thought they were.

The point of all of this is to wonder whether cellphone uptake actually translates to an increase of net developmental productivity – i.e., are people able to do more and make more in terms of their livelihoods – or is it that it has become a new “necessity” and “cost.” (For example, “everyone needs a cellphone now because everyone else has it and not having one is a barrier to entry”). If, indeed, it is that a new “need” and “cost” has been created then that only means that the net “cost of living” has gone up. And, especially for the poor more and more of their disposable income is diverted to this “need” that may not be adding to their productivity or livelihood, but not having which would hurt them. This at a time when the cost of living is already high and economic survival at the individual level under stress (remember where Karachi was on the Global Liveability Index?).

Of course, if the ability of having a cell phone at low cost does, in fact, translate into increased livelihoods (i.e., that the cost of cellphone per person is less than the increase in earning per person because of that cellphone) then the net development benefit would be positive. Even if not, one could argue that development benefits should include (I agree) the non-monetized convenience of having a cellphone; and if this benefit outweighs the costs that society as a whole is better off. What I would like to know whether these benefits do, in fact, outweigh the costs? Or, have we crossed some threshold of excessive cellphone ownership where, despite seemingly low costs, the marginal benefit of ownership no longer exceeds the marginal costs?

Of course, if the ability of having a cell phone at low cost does, in fact, translate into increased livelihoods (i.e., that the cost of cellphone per person is less than the increase in earning per person because of that cellphone) then the net development benefit would be positive. Even if not, one could argue that development benefits should include (I agree) the non-monetized convenience of having a cellphone; and if this benefit outweighs the costs that society as a whole is better off. What I would like to know whether these benefits do, in fact, outweigh the costs? Or, have we crossed some threshold of excessive cellphone ownership where, despite seemingly low costs, the marginal benefit of ownership no longer exceeds the marginal costs?

I do not wish the argument to be taken wrongly. Anyhow, it is more of a question than an argument.

I appreciate that in many developing countries the availability of cellphone cheaply does allow new opportunities to large number of people – including the poor – who did not have those opportunities before. It is also, of course, wonderful for the telecommunication companies and those who work in these companies and related industries (The PTA report – below – says that 1 million new jobs were created). None of this I dispute. The question is about the overall development impact, especially when things overheat. Good? Bad? or Ugly?

So, there. I really would love to get a serious discussion and answers from those who are more deeply involved in this sector. As you think about that, here are some other highlights from the new PTA report:

- Overall teledensity of Pakistan reached 52.8% in December 2007.

- During 2006-07 total telecom revenue was Rs 236 billion.

- Total telecom investment during the year was US $ 4.12 billion and the share of telecommunication sector in GDP was 2.0%.

- Telecom companies have invested over US$ 8 billion during the last four years, mobile sector investment share accounts for 66% of the total investment.

- During 2006-07 the revenue of mobile industry was Rs.133 billion, an increase of 48% from pervious year.

- China Mobile investment is US$ 704 million during 2006-07 for expansion of CMPak networks.

- Mobile Sector paid approximately Rs. 63 billion taxes to the National Exchequer during the year 2006-07.

- Upto December 2007 cellular subscribers in Pakistan reached 76.6 million.

- On average 2.3 million subscribers were added every month during 2006-07.

- Upto June 2007 6,000 cities/towns/villages covered by mobile operators.

- Upto December 2007, total cell sites 17,779 all over Pakistan.

- Today mobile network coverage is reaching to almost 90% of the total population

- The telecom sector received above US$ 1.8 billion FDI, 35% of the total FDI.

- Telecom sector contributed Rs. 100 billion in the national exchequer in terms of taxes and regulatory fee which was 32% higher than the previous year.

- GST/CED collection during the period reached Rs. 36.28 billion.

- Over one million jobs have been created since the deregulation of the telecom sector.

- Rural Telephony Project launched during the year under which 400 Rabta Ghar (Telecentres) are being established in rural areas.

- Total investment in the LDI sector grew upto US$ 603 million in 2007.

- New LDI sector revenue stood at Rs. 15.3 billion.

- At the end of 2006-07 total fixed line connections stood at 4.8 million where as the teledensity is 3.04%.

- There are total of 387,490 PCOs including WLL based PCOs which are working across Pakistan at the end of year 2006-07.

- By June 2007, Broadband subscribers reached 71,000 and 65% of Pakistani broadband users enjoy DSL broadband technology.

- The total teledensity of AJK & NAs was 20.1 in 2006-07 as compared to 3.6 in 2005-06. Overall growth in teledensity in the region due to deregulation is 450%.

- By June 2007, Cellular subscribers reached 912,227 all across AJK & NAs.

It shouldn’t be that hard to estimate teledensity using cellphone sales numbers (combined with estimates of average replacement rates obtained using surveys, for instance), or by surveying consumers randomly on the number of active sim cards they have.

In India, teledensity is computed not by counting the number of sim cards issued, but by estimating the number of unique subscribers. The current estimated teledensity in India is about 25% i.e 25 phones per hundred people. Given Pakistan’s similar economic status and similar development of the telecommunications market, it would be fair to assume a similar teledensity, i.e. about 40-45 million unique subscribers. Perhaps teledensity is a little higher in Pakistan, given that Pakistan is more urbanized.

Any which way one computes the number of unique subscribers, its seems that people carry between 1.5 and 2 sim cards, something that the comments here seem to corroborate.

Dear Adil ji

Perhaps telecom is the only commodity which is crossing the poverty line and going down to the lot, although the people below need atta, ghee, oil and gas/electricity. You have rightly pointed out the exaggerated high percentage. In fact these are the SIMs sold. Maybe 15 to 20% SIMs marketed through various packages have never been energised. PTA ought to have clarified this fact.

We are masters of ‘fudge figures’. Why? because our minds are badly confused and we imagine we are doing it for our survival. Even senior officers, in a bid to show that they have met the targets, give wrong figures. Data compilation is a

burden for us. We give wrong figures so that our bonuses are released. But bosses (I have also been a boss for some), without mindfully seeing it, become happy that the team has done well.

Our plans are generally devoid of basic data; no body is interested. Once a sizeable book is out, all are happy. That is a sad story. Also, if someone does an original work, many people pounce on the opportunity to claim that it was done by him/them!

Sir, we are bunch of also-rans and practically are goners!!

Inna lilla he wa inna ilaihe rajeoon.

Regards.

Sohail

(a retired telecom engineer)

Interesting blog,

I believe teledensity is a great stride forward for Pakistan. If certain policies are in place, like an id matchup with a sim (although it would be hurting personal privacies but thats not there anways), one can have mobile based civic surveys, polls, even elections.

I am currently working on a technology which allows people to check the authenticity of medicines we buy at stores using our mobile fone’s sms and RFID enabled medicine covers. TAXUD have figures that 36% of medicine in Pakistani stores is fake! (I dont want to go into this debate on how this figure was reached and what does constitute a ‘fake’, im taking them as granted). Mobile fones let u authenticate drugs. Ofcourse the more buyers use cell phones for this, the less the shop keeper can sell fakes and even import fakes from his dealers…

I also agree with Tina about Rural usage of Cellphones, i know of people in Agriculture who have benefited in supplying their stock to the ‘sabzi mandees’ with profits due to cellphone’s added value.

Teledensity also allows to spread news (rumors too unfortunately). When Mobile TV becomes a cheaper reality, no more cable operators to deal with. Wifi hotspots will ensure telco operators dont moderate stuff either.

The key to the mobile phone phenomenon in Pakistan is its affordability due to the low price from competition of several mobile firms. The creation of extreme compitition is what has brought low price benefits to the end user.

It is rare in developed markets to have six mobile operators as well as several almost mobile operators (cdma / wll) competing in the same market. Unless tower / backhaul sharing is done between operators, the lower market share operators will ultimately be forced to leave since the fixed cost of running the network is the same for a Mobilink versus Paktel / CMPak.

Also, to cover the same location, there are six different tower sites wasting power, bandwidth and radio resources since resources are not shared. Radio pollution is a topic not even discussed in Pakistan.

Since most mobile operators are only providing their customer numbers but not revenue, it is anyone’s guess how much of these SIMs are dormant. ARPU – average revenue per user would provide a better insight towards the mobile market rather than the numbner of users. Also useful would be the ratio of pre-paid versus post-paid customers that each operators has.

Once aspect important for the overall cost to society is the rate of return that foreign investors are taking from their investments in Pakistan. Cost of the infrastructure + handsets etc is coming out of the revenue that the end users generate in Pakistan and handsets alone are costing couple of billion dollars a year.

As long as the return to foreign investors + costs of handsets etc is offset by the additional GDP that is added to Pakistan’s economy due to mobiles phones, the result is a net benefit to our society.

If only proving education, health services, energy, roads, railways and the rest of infrastructure would be so easy.

At this time, I think our key problem is energy followed by lack of education in Pakistan. Lets hope we dig up some oils wells somewhere or some gold mines.

@Omar Manzur

I agree with you that mobiles are more of a necessity now than a luxury. If you have to pay the cost for this necessity you must.

As for the doubts being created on the figure of 76.6 million, one must look at the demographics. Assuming that none in the rural areas can buy a mobile but everyone in the cities can, because the standard of living is higher in cities, we must try to figure out how many people in the cities would buy the mobiles.

Assuming that Pakistan’s population is around 160 million and also assuming that 40% live in urban areas, that makes a total of 64 million. Also assuming that every child, adult and an old man has the mobile that makes a total of 64 million, which is 12 million lower than the figure of 76.6 million. It means every person in urban areas has on average 1.2 SIMS. But then every child doesn’t own a mobile so it means that actually its more than 1.2 SIMS per person, which is not really impossible since many people including many i know, have more than 1 SIMS.