Guest Post by The Pakistani Spectator

As I write this, I’m very conscious of the fact that I’m speaking from one cultural perspective, as a US-born citizen, who has spent most of his life in California, speaking to an audience in Pakistan, with somewhat different cultural perspectives. I do not pretend that there is any reason why my perspective should be of special interest, or superior to any other – it is just one of many.

As I write this, I’m very conscious of the fact that I’m speaking from one cultural perspective, as a US-born citizen, who has spent most of his life in California, speaking to an audience in Pakistan, with somewhat different cultural perspectives. I do not pretend that there is any reason why my perspective should be of special interest, or superior to any other – it is just one of many.

I also surely do not pretend to have answers to the difficult political questions you currently face in Pakistan, which you of course understand far better than I can hope to, though I hope you might find some of my general thoughts useful as you search for your own answers. If I state something that was already all too obvious, I hope you will pardon the waste of your time.

I also surely do not pretend to have answers to the difficult political questions you currently face in Pakistan, which you of course understand far better than I can hope to, though I hope you might find some of my general thoughts useful as you search for your own answers. If I state something that was already all too obvious, I hope you will pardon the waste of your time.

If I state something that makes good sense to you, from your perspective, but that was not so obvious, I will be very pleased. If I state something that strikes you as simply bizarre, I have likely revealed an area where my assumptions and your assumptions differ, perhaps greatly. When they differ like this, either set of assumptions, or both, may grow through insights that the other can give, and I look forward to learning from your comments to these articles, where you believe I have revealed one of my own cultural ‘blind spots’.

Democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.

– Winston Churchill

Mr. Churchill’s remark on democracy stands as one of his wittier quotes, I think. I also think it is surprisingly deep in its wisdom. Let’s parse what he said:

Democracy is the worst form of government…

At its root, democracy is government by everyone, that is, by ordinary people. It is government elected by voters with ordinary intelligence, ordinary levels of achievement, ordinary levels of education, ignorance, prejudice, selfishness, shortsightedness, laziness, sinfulness – the list goes on! Anyone, however ordinary, could probably list, in a minute or two, a dozen elite groups that would, on average, be more ‘fit’ to govern than the average voter, in terms of all these measurements of ‘fitness’. Name an elite group that you like, and you can make a solid argument that the average member of this group is more fit to govern than the average adult, making democracy, seemingly, worse than government by any reasonable elite.

…except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.

All the all-too-tempting alternatives to democracy boil down to rule by one elite or another, and I believe all these alternatives have, for all their differences, certain properties in common, properties that are inherent in rule by any elite. The elite might be defined by membership within a class, by ‘noble’ or royal birth, by restricted membership within a party (such as under most communist governments), by education, wealth, land-ownership, gender, rank within the military, or position within a religious hierarchy. For most of this article, I will focus on the more exclusive elites. I divide government by elites into four theoretical sub-groups:

(1) Elites defined by birth. Royalty is the prototype for this elite, and it has few advocates, today, as a seat of real power. Kings and queens do seem to make handy figureheads, ‘heads of state’ lacking real power, who can be sent, for example, to important foreign funerals, to show respect, without burdening the busy true leaders of the nation with a lot of time-consuming ceremony. However, a monarchy with real power seems such a discredited system, today, that I don’t think it needs much discussion.

(2) ‘Democratic’ elites defined by arbitrarily restrictive citizenship. Sometimes, a nation calls itself a democracy, with real elections and all the usual democratic institutions, but denies some classes of adults the vote, without just cause. South Africa, during Apartheid, was such a case. Like rule by a monarchy, such systems find few defenders, today they have all the drawbacks of democracy, with simply average voters, while arbitrarily denying justice and representation to those who have no vote.

(3) ‘Democratic’ elites defined by a merit-based right to vote. Some southern states in the US pretended to try something like this, with literacy tests as a requirement for voter qualification. (These tests have been stopped, having been ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court.) In fact, this was a transparent ploy to deny African Americans the vote – the ‘tests’ were operated corruptly so that even the most ignorant whites passed, and even brilliant African Americans ‘failed’, and this experience illustrates the problem. The elite in charge will make sure their children pass the test, and those outside the elite will remain outside, with rigged tests, or rigged test administration, if necessary. No objective test has ever been found that measures true merit, and none is likely to be found, soon.

(4) Elites defined by position reached in a hierarchy. Today, with few ruling monarchies left, almost every non-democratic government is ruled by a hierarchically arranged elite. This case is so common and important that I will spend the rest of the article discussing it.

In hierarchical cases, there are actually many levels of the elite, elites-within-the-elite, that is. Thus, in the old Soviet Union, a small fraction belonged to the elite Communist Party membership, and a small fraction of them belonged to the elite lower-level party officials, and a small fraction of them belonged to the upper-level party officials, and a small fraction of them belonged to the Politburo, and one of them was the Premiere. A similar hierarchy applied in the Catholic church, which exercised considerable political power for centuries – the church granted certain rights (such as the right not to be made a slave) to the minority of humans who were Catholic, and Catholics were in turn expected to be obedient to the much smaller group of priests, who owed obedience to the tiny group of bishops, who were under the tinier group of archbishops, who were under the several dozen Cardinals, who owed obedience to the Pope.

The case of Catholic church political power is interesting in that it existed side-by-side with national rule by kings, elite by birth. The precarious bargain was that the Catholic church leant legitimacy to the kings by certifying that the kings ruled by ‘divine right’, that is, that they were chosen by God, for which the kings owed the church considerable concessions, such as personal allegiance to the church, help spreading the Catholic faith, punishing those who did not strictly adhere to church doctrine of the day, suppression of competing faiths, and laws tending to concentrate wealth within the church. Kings were not, however, much in favor of sharing power, and while the church worked to manipulate kings, kings worked just as hard to manipulate the church, placing their agents within the church hierarchy, even as Pope, and even intimidating the church with military threat where possible. (The church’s power was very much a ‘two-edged sword’, and cost it, and the world, far more than it gained, I very much believe!) This side-by-side power-sharing arrangement was not unique to the Catholic church and European kings. Any time the nominal government shares power with an external elite, whether it be religious, military, party-based, or other, the nominal government will struggle to contain and control the external elite, while ambitious members at the top of the external elite struggle to expand the elite’s de-facto governmental powers.

This sort of power sharing can be politically turbulent and unpredictable for both sides if (as is invariably the case, it seems) the rules for power-sharing are not extremely well-defined and well-followed. (This is true even if the formal government side of the power-sharing arrangement is democratic!) Either side can lose control that it took for granted, through ‘back-room’ maneuvering from the other side bent on expanding its control. In the case of the external elite, such back-room maneuvering may not only take away its power within the government, but likely will also compromise its external purpose. For example, if a religious hierarchy has some governmental powers, ambitious people in the government sharing that power will work insidiously to control the religious hierarchy, if necessary by corrupting it. This will likely have the side effect of harming the religious organization’s primary mission of helping more people to be more obedient to God (or whatever that religion defines as its the primary mission, which may depend on the religion).

All hierarchical elites seem to have much in common: People enter the hierarchy ‘common-soldier level’ by persuading a lower-level ‘officer’ (or manager) in the hierarchy to let them in. People rise in the hierarchy by persuading an ‘officer’ two levels above them to ‘promote’ them to rise to the next level. (Any given officer must work within ‘budgetary’ constraints set from the highest levels that limit how ‘heavy’ any branch of the tree may grow, so promotions cannot just be handed out (or sold) without limit.) Reaching the very top of the hierarchy is the least-well-defined step, often. It is usually not even possible to reach the very top without death or voluntary (or, behind the scenes, more or less coerced) retirement at the top, and then some sort of voting process among those at the very top of the hierarchy chooses the new ‘premiere’. This highest level, however, usually consists of a set of extraordinarily ambitious persons, and the sort of deal-making, backstabbing, coercion, and power-trading that can go on in this highest-level selection of the ‘premiere’ can be frightening and dangerous, even leading to civil war.

Consider the evolution of a hierarchical elite that ends up running all or part of a government:

In the beginning, the elite might have some very focused mission that has nothing to do with government. If it is a religious elite, the mission might be to help people obey God’s will. If it is a military elite, the mission might be to defend the country. (Elite hierarchies seem least likely to grow corrupt where the mission is narrow and focused, without broad power to tempt the corrupt.) If it is an economic elite, the mission might simply be to gain more wealth. Whatever the mission, individuals climbing the hierarchy may be more focused on achieving the mission than on simply climbing the hierarchy per se. The interests of the leaders of the elite may be well-aligned with the mission, therefore. (However, do not underestimate the role played by status-seeking. Even in the most virtuous organization, humans may be tempted purely by the status that goes with leadership roles in the organization.) Before the hierarchy gains government power, it may be relatively ‘pure’ and uncorrupted in its focus on its original true mission, and the leaders may be admirable and virtuous, themselves, having climbed to where they are for all the right reasons, simply because they cared passionately about the original mission of the group.

Consider the next step in the evolution of the hierarchy, when the hierarchy gets government power: Now the hierarchy holds serious, worldly power and coercive access to other’s wealth. At this point, the hierarchy becomes the path to raw power, regardless of the original mission. Who, now, will climb the hierarchy? At each stage of the selection process, to reach the next level, there will be a tendency for the most ambitious and even ruthless to reach the next level, often by flattering, threatening, blackmailing, or otherwise corrupting the immediate superiors who control the climb in each branch of the hierarchy. With real stakes for worldly power, there is no shortage of people willing and able to do whatever it takes to corrupt the process to climb to positions of high influence (if necessary, faking virtue to fool those above them who are not yet corrupted). Over all too short a time, the highest levels of the hierarchy ruthlessly self-select for raw ambition and ruthless willingness to do whatever it takes to grab raw power, with each level more ruthless than the level below it. Note that it takes only a few imperfect people anywhere in the original hierarchy to corrupt the whole hierarchy. If even a tiny corrupt minority gains a foothold in the hierarchical tree, that minority will let in allies, and will work inexorably to corrupt, undermine, and replace the honest majority, who face an uneven battle, since they fight by more honest rules.

Consider the next step in the evolution of the hierarchy, when the hierarchy gets government power: Now the hierarchy holds serious, worldly power and coercive access to other’s wealth. At this point, the hierarchy becomes the path to raw power, regardless of the original mission. Who, now, will climb the hierarchy? At each stage of the selection process, to reach the next level, there will be a tendency for the most ambitious and even ruthless to reach the next level, often by flattering, threatening, blackmailing, or otherwise corrupting the immediate superiors who control the climb in each branch of the hierarchy. With real stakes for worldly power, there is no shortage of people willing and able to do whatever it takes to corrupt the process to climb to positions of high influence (if necessary, faking virtue to fool those above them who are not yet corrupted). Over all too short a time, the highest levels of the hierarchy ruthlessly self-select for raw ambition and ruthless willingness to do whatever it takes to grab raw power, with each level more ruthless than the level below it. Note that it takes only a few imperfect people anywhere in the original hierarchy to corrupt the whole hierarchy. If even a tiny corrupt minority gains a foothold in the hierarchical tree, that minority will let in allies, and will work inexorably to corrupt, undermine, and replace the honest majority, who face an uneven battle, since they fight by more honest rules.

Looked at in the abstract, it’s not hard to see the dangers, and even the inevitability of corruption in a hierarchical elite handed government power. In the abstract, the problem may seem all too obvious. The trick, too often, comes when we apply these lessons in the concrete, specific case. Oh, sure, power corrupts, but my wonderful, honest organization will avoid the pitfalls! Don’t believe it! However wonderful an organization is, today, unchecked power can and will corrupt it, like rot, in the end. It will turn the most honorable organization of humans into a pathetic parody of its former self, perhaps in a few years, perhaps in a decade or two. Do you want a solution for today, or a solution that lasts for your children, and your grandchildren?

So, how is a democracy any better? Isn’t a democracy also run with a hierarchical bureaucracy run by ambitious men and women at the top, with even more ambitious men and women elected to office, at the very top? This is true! Democracy doesn’t change human nature, or the incentives to seek and abuse power. The key difference is simply that in a democracy there is a feedback process that tends to push in the direction of the people’s interests. Elected officials may have their own agendas for their use of power, but in the end, they would like to hold what power and prestige they have. They know that if the government does not at least approximately serve the wishes of the voters, they increase the risk that those voters will throw them out. If the leaders in control in a democracy abuse their power too badly, too much against the interests of the voters, the party or parties outside the majority in Parliament, or Congress, or the Presidency, will eagerly spread the message to the voters, and will take their turn in power. If individual elected leaders choose to abuse their personal power at the expense of their party’s long-term prospects, the parties will tend to restrain them, to protect the party’s long-term access to power. Non-elected bureaucrats may abuse their power, too, but the elected officials who (with difficulty!) exercise final authority over the bureaucracy will set and enforce the bureaucracy’s rules to restrain the bureaucrats from enriching themselves too easily at the expense of the elected leaders’ long-term hold on power. A free press and free speech play a vital role, here, in helping voters know the true state of things, so they cannot be so easily fooled into thinking that the powers in charge are fulfilling their promises, when they are simply serving themselves.

Good, universal education, too, is vital. Uneducated voters are far easier to fool, to buy with empty promises or to sway with false fears. (No nation is immune to this, least of all my own, as shown well in the elections of 2000 and 2004!) Uneducated voters are far more likely to focus on short-term desires (such as are served by tax cuts the government cannot afford, or poor protection of the environment), at the expense of their long-term well-being, and their children?s.

(You may notice an unstated assumption in my discussion, so far, that government’s legitimate role is to serve the people. I certainly believe this, but I haven’t discussed why. Is there a better mission for government than to serve the people? That will be a topic in a future article!)

Whether government is a democracy or is run by an unelected elite, can the ambitious people who reach the top be ambitious to do good, to help the government serve the people? Certainly, ambition and virtue can co-exist! In any government, people who are ambitious to do good will compete for the top levels with people who are ambitious only for themselves, for raw power, prestige, and wealth. Without feedback from the voters, however, the ‘game’ of rising to the top of the hierarchy is stacked against the honest ‘players’ who just want to do good, while in a democracy, at least the more honest ‘players’ have a fighting chance, in the end! (In the US, few people who just want to get rich work in the government – the system makes large-scale corruption difficult enough that there are many easier ways to get rich, even to get rich honestly, outside of government!)

Whether government is a democracy or is run by an unelected elite, can the ambitious people who reach the top be ambitious to do good, to help the government serve the people? Certainly, ambition and virtue can co-exist! In any government, people who are ambitious to do good will compete for the top levels with people who are ambitious only for themselves, for raw power, prestige, and wealth. Without feedback from the voters, however, the ‘game’ of rising to the top of the hierarchy is stacked against the honest ‘players’ who just want to do good, while in a democracy, at least the more honest ‘players’ have a fighting chance, in the end! (In the US, few people who just want to get rich work in the government – the system makes large-scale corruption difficult enough that there are many easier ways to get rich, even to get rich honestly, outside of government!)

For all its weaknesses, a democracy of all the people is the only system known that has reliable feedback, a control that tends to push ambitious leaders consistently over time in the direction of at least approximately serving the interests of the people. Democracy is the only system known that can reliably discard obviously corrupt, selfish, or foolish leadership without tragically bloody revolution. (Without democracy, bloodless revolution is still possible, and highly commendable, and much more likely to lead to a government better than it replaces, but it is surely never easy!) The broadest possible democracy, democracy that does not exclude classes of adults as voters, and that does not share government power with any elite unappointed by and uncontrolled by elected leaders, will best serve the broadest interests of the people.

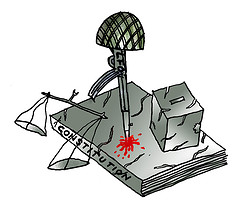

Photo Credits: Abro

FACTS ON THE GROUND IN PAKISTAN.Reference to the Islamic history and Pakistan

Please read the articles, “Is Democracy Alien to Islam?” and ” A Critique of Democracy,” on my blog.

Democracy and the status of voting in Democracy from the Islamic perspective

http://tinyurl.com/2qyh5z

Clarifying some of the erroneous views being spread, that legitimises voting in Democracy:

If you do not allow this comment to be posted like you haven’t allowed my other comments, at least let everyone know why this comment is inappropriate.

Deewana Aik ji

The third world (including more than half of muslim

countries) is unable to see Islam’s authenticity, down to earth attitude and solutions, for the following reasons:

Their illetracy rate very high. Soaring joblessness.

The infos about Islam and its universal spirit have

not reached, who to blame ?? we all know !!

The poverty and subsequent priorities, which are e.g

quick solutions like Tourism, showbusiness, weak

and unrelyable small industries already victim of

globalisation, and dislocation, high prices, monopoly

of G8 etc. The 3rd world is condemned to stay as it is.

The “religion ” in these parts of the world(non-muslims)

means nothing but unauthenticity of belief offered

to them, based on incomparison between clergy and layman, resulting in “fed up with all ” reactions. Astonishingly, yet Islam is the only fastest growing

religion in the world.

On the other hand muslims are unable to convince

others about Islam, which does not simply depend or

rely on them.

So the dilema is, that muslim’s role seems to be evacuated

from the whole debate. Quran is so powerful, even we

muslims hav’nt got the slightest idea.

Now, about MMA’s parties, majority of them are

playing exactly the same role as played during

Ummayad’s dictatorship, I call them “cloned” doleys

either Ullemahs or likewise, the whole continuity is

repeated every century in the name of corrupt

intrepretations exploited to let down the layman.

Few Ullemahs exist in Pakistan, but you can count them

on your fingers.

The problem is people like you, me , others, thems do’nt

look into the anals of the history and learn from the

disastrous, fatal, selfish and corrupt attitude.

I will be giving you a shock, telling you that I have read

in the Ummayad’s history , an Arab learned alim

beaten up in the street, because he was married to a

persian lady, then he was forced to divorce her,

because she was not arab.

No way, if they are Ulemas so they know the best ,

nonsense.

Asalam Alaikum

We deserver democracy but what kind of?

Do you see any political or religious political party in which you see party democracy? Why not have a look at the most popular political party in Pakistan.

Pakistan’s 50 years of politics is divided in 25yrs by Army Generals in the form of Martial Law and 25yrs by Civil Governments on the name of Democracy. We left Martial Law Administration as most of people believe it is not democratic or etc. But the 25yrs Civil Governments what they gave on the name of democracy. Unlawness, Nationalism (Quam Parasti), Ignorance or unequal rights to all four provinces and peoples their especially small provinces like Sindh, Balochistan, and NWFP. Now a days Pakistan’s population is 16coror and the tern over of total voters in four provinces after 50yrs is 5crores. The majority of Pakistani is not with any political party or can