Adil Najam

Adil Najam

Reader Naveed Ejaz recently sent me a link to a new blog he has started called Rethinking Disability. I was finally able to visit and explore the blog today. I was left extremely moved.

The site is exactly correct in pointing out that we, as a society, are caught in “prejudiced molds” of thinking about the disabled. We at ATP also stand guilty of not having raised these issues as we should have (we did do one post on the Pakistan Blind Cricketers Team winning the Blind World Cup; but that is not at all sufficient).

I would particularly recommend a post called The Pink Elephant; but first a bit about Naveed Ejaz – and I reproduce this imply because he has done so on his site and I think it is relevant to understand what he is saying and why:

I am a 25 year old male, born and raised in Pakistan, a developing country by every meaning of the word. Blessed with amazing resources and even greater parents, I have been educated both within Pakistan and abroad. But more importantly for the purposes of this debate, I have cerebral palsy, a physical condition that predominantly affects my mobility, meaning therefore that I am disabled, handicapped, impaired, disadvantaged, invalid and abnormal. Despite the wealth of adjectives at their disposal, my family and friends still prefer to call me by my first name. Some people however insist on calling me by my full name, but I really do not care for that all that much.

The first part of this paragraph provides you context on who the person is. The second half tells you how he thinks. It is the second half, I believe, that is far more relevant.

But even more important than how he thinks, is what he wants us to think about. Here are a few powerful examples; and we would all do well to pay attention:

Imagine the happiest day of your life. For those with an overactive imagination and Freudian tendencies, I urge you to stop here. For many this would bring up images of the day they got married or the birth of a child. Close your eyes and savor and rejoice in the purity of the moment for a while.

Now imagine that your spouse/child is disabled.

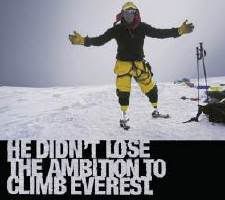

The dream ends here; entering unchartered territory that we feel uncomfortable exploring. Herein lies the biggest problem regarding our collective perception of disability. It is a problem that is discussed at an arms length. Much like sexuality, disability is a taboo subject even when considered as part of a serious debate. It is the unnamed pink elephant (for those wondering why pink, kindly refer to a child in the family to tell you the joke) in the living room that no one is comfortable talking about. Being part of the disabled club is then akin to being part of an unwanted minority – a collective being that is considered to be a-religious, a-sexual and non-functional. Discussions regard the role of this minority within society have always been refrained from, primarily for fear of sounding politically incorrect. While the situation is not that pronounced in developed countries – they too have their own problems regarding the subject – where the rights of individuals are stressed upon, it is the third world where conditions are most dire. Unless each and every member of our society warms up to this debate, the situation will continue unabated. For too long now, we have looked for the perfect, politically correct word to describe this group, and in doing so failed to address the core issue at hand i.e. its role.

If that did not catch your attention, then please stop reading; because nothing will.

If it did, then here is some more:

The problem as it exists in the third world today is essentially two pronged in that (i) the society expects the disabled to be less contributing members and (ii) the disabled believe themselves, in some way, to be less contributing members of society.

Simply put, the role of the disabled is no different from the role of those who are healthy. At this point, I must admit to setting up my argument of choice by intentionally using the word healthy as a contrast against disabled, but it is a contrast that is subconsciously accepted to us all. A disability is an aberration, an unwanted trait, a statistical and Darwinian anomaly. Webster dictionary too defines disabled as being ‘incapacitated by illness or injury’; the obvious reference to health. Grammatically, however, disabled – and all other synonymous words – seems to indicate the lack of an ability or skill. The obvious contrast then to health is sickness and for disabled is abled. One is a state of well-being, the other a functional attribute, and while the presence of a disability might give rise to risks in health, accepting the two as contrasting opposites gives rise to problems of repression.

There is a reason why physically handicapped beggars earn more than their able-bodied counterparts in a day. I do not wish to dwell on the socio-economic implications of begging, but merely to illustrate the subconscious pity we have for such individuals which drives us towards greater charity. Pity is possibly the strongest of human emotions, and by indulging in it one subconsciously assumes superiority over the other. It is pity that drives us to assume that the individual cannot achieve much within the limitations the disability imposes. It is pity that projects a feeling of repression on the disabled. It really is a pity that the disabled are faced with not only proving to themselves, but also to society that they are fully functional human beings within their own rights. While collectively, we can do little to alleviate the mental struggles that the disabled are faced with, we can ease the burden by being more accepting and not having them prove their worth time and again. In order to move forward, our acceptance of individuals needs to expand beyond our peripheral senses and into the functional realm.

There is more in the article that is worthy of attention, including the role of culture and religion in cementing stereotypes. But let me leave you only with the authors’ concluding paragraph:

The disabled are here to stay. They have as much right to be part of society as you and I. The sooner we accept the barriers that impede their path, the sooner efforts can be undertaken to remove them. Changing mindsets is the key, both on the collective as well as the individual level. It is essential that we break our minds of our prejudiced molds. It is imperative that the disabled view themselves as functional beings and it is critical that parents do not shy away from seeking professional help for their child. All this is only possible if we all make the conscious effort to think about it.

Regular readers of ATP will recognize why I am so inspired by Naveed and his blog. The key is really – it always is – in whether we (and how we) think about things. It is the matters of the mind that our real challenges lie. The recent silliness of debate on our own blog demonstrates (as if demonstration was necessary) that the real fatoor lies in the minds of men. It is from the same source that the solutions must emerge. Action is always important. Indeed, it is necessary. But just like thought without action will give you mere slogans; action without thought will leave you only with ritual.

So, I for one, pay great heed to Naveed’s words. Think. Think, as if you life depended on it. It may well!

Thats right society owe more than what she does to these people. In Canada, instead of calling them diasabled, they are called “special needs” people.

I know one of inlaw’s cousin whose leggs were effected by polio and wasn’t able to walk. She graduated and then started to work at radio station. She was well maintained and enjoying life at full extent. She married to a sincere lover and now is a mother of one boy. After seeing her, I always believe if she can live a full life, then others too.

One more point. We usually think of the disabled and immediately think of beggers, etc. But there is also the silent and important issue of how middle and even upper class families treat children with disabilities. Often trying to ‘shielf’ and ‘protect’ them so much from an unfair society that they never give these individuals the opportunity to reach their own potentials.

Aqil raises a very thought provoking point. The disabled are ‘forgotten’ and ‘neglected’ in multiple ways and even looking at the current discussions here it is striking how w spend so much energy on debates that will probably lead nowhere but fail to even consider issues on which, maybe, if we tried, we could actually do something.

I first want to commend Prof Najam for bringing up this badly ignored issue.

Let me say something provocative about the lack of attention on this issue (please don’t misconstrue the point and get off on other tangents)

Just ask yourselves the following questions:

1. What is the percentage of Pakistanis with disabilities?

2. What is the percentage of people belonging to religious minorities in Pakistan?

3. How much time do we spend thinking about the two?

I certainly don’t wish to make any comparisons between the two issues, religious minorities face problems of another kind, whereas people with disabilities have to deal with discrimination of a very different kind. I am also not in favour of counting people and comparing numbers; my point here is very different.

I just want to point out that when people talk of human rights in Pakistan, they talk about women and religious minorities, but the disability issue seldom even gets mentioned among the major human rights violations.

A purely innocent case of overlooking an issue due to its socio-economic dimensions, or lack of its ‘sex apeal’ (the world cares so much about our women and religious minorities, especially when a bit of Pakistan bashing is required, but the disability issue perhaps doesn’t give them as much milage in their propaganda) or a combination of both factors?

May be if and when it starts to suit the west and India (yes, India too) to give us hypocritical and self-serving lectures on the importance of treating people with disabilities as human beings….

Rai.T.U.Khan, with regards to sexual ability, you have heard right. Disabled people are fully functional sexual beings, although conditions vary depending upon the nature of the condition.

Most disabled are aware of their sexual abilities and limitations, yet are worried that that their children might inherit their condition. In cases where the disability is as a result of neural damage with no subsequent effect on the genetic code of the individual, the child has no risk of inheriting the disability. However disabilities such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) and Huntington’s Disease (HD), which arise as a result of genetic mutation, do increase the off-springs chances of contracting the condition as well. However, even in such cases, the chances of the child being ‘normal’ exist.

In all cases, it is always best to consult a physician before arriving to any positive or negative conclusions.