Adil Najam

Adil Najam

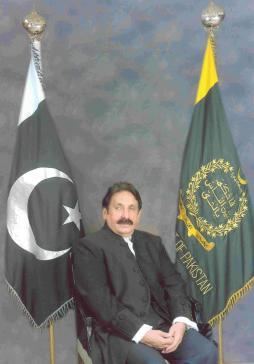

In a rather shocking move, the President, Gen. Perzez Musharraf just dismissed the current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, Iftikhar Mohammed Chaudhry for alleged “misuse of authority.”

According to a breaking news segment at The News:

The president has submitted a case against Chaudhry to the Supreme Judicial Council. Musharraf had received “numerous complaints and serious allegations for misconduct, misuse of authority and actions prejudicial to the dignity of office of the chief justice of Pakistan,” and Chaudhry had been unable to give a satisfactory explanation, sources said. The report did not specify what he was accused of. The council is a panel of top Pakistani judges that adjudicates cases brought against serving judges and will decide whether the charges against Chaudhry merit his formal dismissal and whether he should be prosecuted.

Basing their story on the Associated Press of Pakistan, the BBC reports further:

Mr Chaudhry was summoned to explain himself to Gen Musharraf and Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz. His case was then referred to the Supreme Judicial Council which will decide if Mr Chaudhry should be prosecuted.

The move has shocked many, but signs of its coming can now be identified in hindsight. Mr. Chaudhry had served as the Chief Justice since 2005 and, on occasion, had taken steps that had irked the power structure in Pakistan.

According to a Khaleej Times report, for example:

Last June, the Supreme Court rejected a government move to sell 75 percent of state-owned Pakistan Steel Mills to a Saudi-Russian-Pakistani consortium for 21.7 billion rupees ($362 million). Mill workers claimed it was greatly undervalued. Also, Chaudhry has heard a landmark case brought by relatives of dozens of people believed taken into secret custody by Pakistani intelligence agencies. The chief justice has pressed the government to provide information on the detainees whereabouts. Talat Masood, a political analyst, said the removal of Chaudhry demonstrated the power of the military and suggested that Musharraf’s government wanted to have a “pliable judiciary” ahead of parliamentary elections expected later this year. Musharraf, who took power in a bloodless coup in 1999, is widely expected to seek another five-year term as president from parliament this fall.

Recently, an open letter from Advocate Naeem Bokhari addressed to the Chief Justice and making a number of allegations against him – some personal – has been circulating on the internet extensively. Over the last week, I received probably two dozen emails with that letter in it (many from our readers, and one from my mother!). It seems to have created a stir. Many readers have been writing that we do a post on that letter. I had not done so, just because the letter was a little puzzling to me and its motivations were not clear. I wondered also if there were hints of personal rivalries or issues. On the other hand it was a well-written and seemingly sincere letter from a person of known integrity. In retrospect, the way the letter ended was prophetic:

Recently, an open letter from Advocate Naeem Bokhari addressed to the Chief Justice and making a number of allegations against him – some personal – has been circulating on the internet extensively. Over the last week, I received probably two dozen emails with that letter in it (many from our readers, and one from my mother!). It seems to have created a stir. Many readers have been writing that we do a post on that letter. I had not done so, just because the letter was a little puzzling to me and its motivations were not clear. I wondered also if there were hints of personal rivalries or issues. On the other hand it was a well-written and seemingly sincere letter from a person of known integrity. In retrospect, the way the letter ended was prophetic:

My Lord, this communication may anger you and you are in any case prone to get angry in a flash, but do reflect upon it. Perhaps you are not cognizant of what your brother judges feel and say about you. My Lord, before a rebellion arises among your brother judges (as in the case of Mr. Justice Sajjad Ali Shah), before the Bar stands up collectively and before the entire matter is placed before the Supreme Judicial Council, there may be time to change and make amends. I hope you have the wisdom and courage to make these amends and restore serenity, calm, compassion, patience and justice tempered with mercy to my Supreme Court. My Lord, we all live in the womb of time and are judged, both by the present and by history. The judgement about you, being rendered in the present, is adverse in the extreme.

In all honesty, one has to wonder, however, whether it was that letter and other recent media focus on the Chief Justice that led to the removal of the Chief Justice, or whether these were merely instruments designed to prepare the way for this removal?

In either case, a removal of the Chief Justice in this way and for such reasons and at this time is a sad, sad development that will be one more blow to the hopes of the development of an independent judiciary in Pakistan.

Note: At various points we have reproduced, in our right-most column, cartoons from Daily Times (and here) and The News.

I’ve ripped and uploaded the Kamran Khan show that contained an interview of the Chief Justice’s son as well, regarding his transfer to the FIA.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

And Dr. Shahid Masood’s take on the same event

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Has anyone noticed how press reports in Pakistani media have started using the words “non-functional Chief Justice” to describe teh Chief Justice. As if that was a real title. What a joke we make of everything. Remember how until so recently we had a ‘Chief Executive’ instead of a President or Prime Minister. And how quickly everyone falls into like and starts using these ridiculous descriptions and treating them as real!

Example from The News: http://thenews.jang.com.pk/updates.asp#19225

An excellent article — From The News, March 11, 2007

The intrigue of justice

By Babar Sattar

The independence and integrity of the Judicature has been gravely tarnished with General Musharraf suspending the Chief Justice of Pakistan in violation of Article 209 of the constitution. In theory, independence of the judiciary is a grundnorm of Pakistan’s constitution, ensured in part by the constitutional security of tenure afforded to superior court judges. The constitution states that no judge of the High Court or Supreme Court can be removed (temporarily or permanently) from office except in accordance with the constitution. Article 209 then provides the mechanism wherein the president can remove a judge on the Supreme Judicial Counsel’s recommendation if, after conducting an enquiry, the counsel finds that the judge is (i) incapable of performing the duties of his office or (ii) is guilty of misconduct.

The Supreme Judicial Council comprises the Chief Justice of Pakistan, the two most senior judges of the Supreme Court, and the two most senior Chief Justices of the High Courts. In the event that an inquiry is being conducted against a judge of the Supreme Court, who is also a member of the Supreme Judicial Council, the next judge in the order of seniority is included in the council in place of such judge under inquiry. Under the constitutional system of checks and balances, the president only has limited discretion with regard to removal of a judge in terms of (i) directing the council to conduct an inquiry against a judge, and (ii) removing the judge if found culpable by the council. Neither Article 209 nor any other article of the constitution authorises the president or any other institution or individual to suspend any judge or declare his judicial office dysfunctional pending the Supreme Judicial Council’s inquiry.

The suspension of Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammed Chaudhary is extremely disturbing, not just for the disgraceful way in which it was done or being questionable under law, but also for its long-term implications on the already distressed credibility of our justice system.

First, the fundamental principles of law that no man can be condemned unheard (audi alterm partem) and that a man is innocent unless proven guilty has been breached by the Musharraf Regime. The chief justice is not a petty state official who can be suspended pending inquiry. No judge can be condemned without being judged for misconduct and found wanting by the Supreme Judicial Counsel. If the judicial office or a judge under inquiry was required to be temporarily suspended by implication, the constitution should have explicitly provided for such suspension just like it provides a mechanism for a the replacement of a member of the Supreme Judicial Council under inquiry. If a president subject to impeachment proceedings can continue to hold office, there is no reason why the chief justice cannot, so long as he is not found guilty of misconduct by his peers and removed by the president. It would be within the discretion of a judge to refuse to discharge judicial responsibilities pending inquiry, just as it is within his discretion to determine numerous other conflicts of interests that might inhibit a judicious performance of his duties.

Second, the chief justice stands indicted due to his suspension and is unlikely to get a fair inquiry by the Supreme Judicial Council. The appointment of Justice Javed Iqbal as the acting chief justice is a violation of Article 180 of the constitution, which states that an acting chief justice can only be appointed when the Chief Justice of Pakistan is absent or unable to perform the functions of his office. None of the circumstances that necessitate the appointment of an acting chief justice existed. Also, the inclusion of Justice Javed Iqbal in the Supreme Judicial Council creates a conflict of interest. Only finding the chief justice guilty of misconduct would enable Justice Javed Iqbal to become the Chief Justice of Pakistan as otherwise he would retire prior to expiry of the term of the current chief justice. There is scant possibility of a fair enquiry being conducted by a council of peers led by a judge who has a personal interest in the outcome of the inquiry. Further, his appointment as acting chief, if made permanent, will also be a violation of the principle of seniority as Justice Rana Bhagwandas is the senior most judge of the Supreme Court after the chief justice.

Third, the prima facie evidence of the alleged misconduct and the manner and timing of the media trial conducted to bring the chief justice into disrepute makes the whole exercise suspect. Mr Naeem Bokhari wrote an exceedingly incriminating letter to the chief justice making insinuations regarding nepotism and abuse of office for pomp, apart from charging him with breach of dignity of judges and lawyers and blemished dispensation of justice. Many of Mr Bokhari’s allegations found resonance in the legal fraternity due to the gruff conduct of the chief justice as well as his fascination with cars and media that is considered unbecoming of a judge. But the letter also got appreciated and widely circulated for being seen as a truthful account of a lawyer, written in the interest of justice at the peril of being penalised for candour. While the suspicious saw the missive as part of a larger conspiratorial design, it was only after the chief justice was suspended that the Musharraf Regime’s strategy became obvious.

It is not hard to fathom why the chief justice is being banished: he began to take the constitutional guarantee of judicial independence too seriously and began to poke the judicial finger into holy waters. The chief justice’s judicial activism in the matter of missing people did not sit well with the military. The military regards determination of all security issues as falling within its exclusive domain and discretion. The chief justice’s notion of judicial autonomy and his campaign against the indiscriminate retention of citizens by security agencies were interfering with the military’s notion of operational autonomy. Further, in 2007 the Supreme Court will be called upon to take significant constitutional decisions, including (i) the issue of legality of General Musharraf’s simultaneous holding of the offices of president and chief of army staff, and (ii) whether the present assemblies are competent to elect General Musharraf for another term. Public responses of the chief justice on the judicial outcome of such legal controversies were not reassuring and he could not be relied upon to continue to mould the constitution to keep the general indefinitely in power.

The personal conduct and mannerism of Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhary has been unbecoming of an exemplary judge. He also seems to lack the vision, charisma and temperament fitting of a leader likely to inspire confidence and transform the judicature into an emblem of public trust. But such critique is no ground for the chief justice to be removed from office. It took eight years after the unceremonious (yet honourable) dismissal of Chief Justice Seed-uz-Zaman Siddiqui along with other esteemed judges for the apex court to acquire a modicum of independence. If the Supreme Judicial Council removes Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhary from office out of fear or intimidation or pique, the credibility and integrity of the judiciary, already in scant supply, will suffer grievously. Palace intrigues belong to chambers of power and not to the house of justice. The guardians of the constitution should not get their hands further sullied.

The writer is a lawyer based in Islamabad. He is a Rhodes Scholar and has an LL.M from Harvard Law School. Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

I’ve ripped and uploaded the Kamran Khan show that contained an interview of the Chief Justice’s son as well, regarding his transfer to the FIA.

Part 1: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wGebI74dEzE

Part 2: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4GNiuiMD9c

Part 3: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgntWjI5Ksk

Part 4: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WrV-odEvMjs

Meray Mutabiq – Dr. Shahid Masood’s take on the same event.

Part1:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCWVi8XzQTU

Part2:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nA9i3FwRQsU

Part3:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4s5_6Dj6Ch4

Part4:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ppmXrVZprEU

Editorial, The News, March 11, 2007

Beware the ideas of March

To say that the ‘suspension’ of the Chief Justice of Pakistan, Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry, upon the filing of a reference by President Pervez Musharraf under Article 209 of the Constitution is a controversial move would be an understatement. The chain of events set in motion on Friday by the filing of the reference is only going to further exacerbate the rocky relationship between the executive and the judiciary. First the facts as they stand: the president does have the constitutional right to file a reference under Article 209 with the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC) if he receives “information” that a judge of the Supreme Court or the High Court “may be incapable of properly performing the duties of his office by reason of physical or mental incapacity or may have been guilty of misconduct”. The chief justice was, according to several news reports, summoned to meet the president at the latter’s camp office where he was asked to explain the allegations in the letter. According to the official APP news agency, he failed to give a satisfactory defence and was told that a reference was being sent to the SJC against him on the grounds contained in the letter (this was also corroborated by the minister of state for information in his appearance on a TV show). The SJC comprises the chief justice of the Supreme Court, the next two most senior judges of the Court and the two most senior chief justices of the high courts. Since Justice Chaudhry himself would be heading the SJC in normal circumstances, his place will be taken by the Acting Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Javed Iqbal. However, it is unclear whether Justice Rana Bhagwandas, next in seniority after Justice Chaudhry and reported to be presently on leave abroad, will be included in the SJC when it takes up the presidential reference this coming week. Of course, all this may come to naught — the hearing of the reference by the SJC, that is — if Justice Chaudhry chooses to resign.

The facts, however, do not end there. The basis of the reference, according to the minister of state for information who said this to a private television channel on Friday, seems to be a letter written by a Supreme Court advocate and otherwise well-known personality which contained allegations that Justice Chaudhry had turned his courtroom into a “slaughterhouse”, that he was seeking protocol over and above that due to someone holding his post, that he used his influence to get his son posted in the police after he failed to qualify and that he would announce short orders but would change the verdict in the written judgement. There were other allegations as well but these seemed the more substantive ones. However, no allegations of financial impropriety have been laid in the letter (the text of the reference, though, has not been made public). As far as the issue of appointment of the acting CJ is concerned, the ministers of the government have been saying that the next most senior judge, Justice Rana Bhagwandas, who should have been appointed according to the Constitution, was on leave and outside the country. Given this peculiar situation with a reference filed against the chief justice himself, if the reference is indeed heard by the SJC there may arise the possibility that one of its members benefits from its eventual outcome.

It would be fair to assume that many people will see this run of events with suspicion. In fact, some have linked it to a statement made by a leading politician recently linking a possible declaration of a state of emergency as a justification for extending the National Assembly by one year. Many will also link the action taken by the government with the fact that the chief justice was a strong proponent of judicial activism and that some of this may have stepped on powerful toes. For example, the Supreme Court struck down the Pakistan Steel Mills privatisation deal which was an embarrassment for the government, took strong note of the New Murree project which had strong vested interests backing it, and of late had been regularly hearing petitions filed by relatives of citizens claiming that the latter had been detained incommunicado by government intelligence agencies. During the course of these hearings, revelations came to light which again caused some embarrassment for the government because some of the disturbing allegations seemed to have been correct.

As already pointed out earlier, the Supreme Judicial Council is to meet this coming week and has invited Justice Chaudhry to present his side of the story. Pending that hearing and pending the SJC’s examination of the said reference, and upon receipt of its recommendations by the president, Justice Chaudhry will not perform his duties as Chief Justice of Pakistan. Because this hearing is yet to take place, it is premature to comment on this aspect of the matter. However, questions are bound to (and should) be asked, especially about the manner in which the chief justice was summoned and the reference against him filed on the basis of a single letter (so far we have been made to understand that this is the case). Some jurists, among them former Supreme Court judges and lawyers of considerable standing, have questioned the government’s decision to suspend the chief justice: they say that while the filing of the reference is very much within the president’s powers under Article 209, the matter of suspending the highest judicial officer in the land is not. The argument — a cogent one — runs along the following lines: it is a canon of justice that no one should be condemned unheard and that suspension is not something envisaged under the said article. Of course, common sense would require that any judge against whom a reference has been filed with the SJC and if he is eligible to be a member of the SJC should himself step aside. However, so the argument goes, this is not something that Article 209 is categorical about. Of course, there is also the general observation — being made across the board — that the allegations mentioned in the letter may be difficult to prove other than the posting of Justice Chaudhry’s son for which there may well be documentary evidence (such evidence, however, may well implicate the government itself, since it would show that it acquiesced to the request). Further, should a request for protocol be held against any particular government officer given that it is now the norm for senior state functionaries to expect such treatment? These arguments and counter-arguments are bound to go on and may well intensify in the coming days but one thing is for sure: what happened in Friday is certainly not a red letter day as far as the state and its relationship with the judiciary is concerned. One now waits anxiously for the SJC’s meeting scheduled for this Tuesday — provided nothing further happens before that.