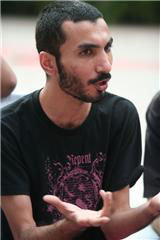

What distinguishes Asim Butt from his generation and perhaps the preceding generations of artists is the sheer originality of his vision and an iconoclasm that is neither trumpeted nor made visible until the subtext of his lines is closely studied.

This is why Asim has undertaken bold strides during the last 10 enriching years of painting. In the meantime, he also earned a degree or two in social sciences, a half-finished PhD at the University of California and formal training from Karachi’s Indus Valley school of Art and Architecture.

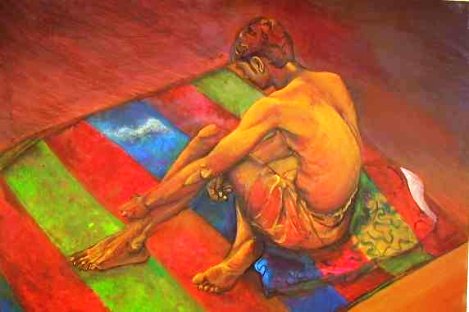

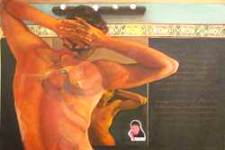

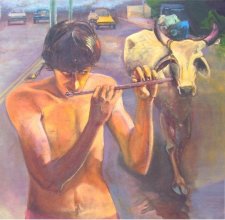

Art education in Pakistan, despite its deep- seated tradition of experimentation, does not allow the full exploration of originality. This is why the revival of miniatures has become another soft tool of marketisation and an out-of-wedlock union between art and commercialism. Rejecting what is on the horizon of Pakistani art, Asim Butt has stuck to his innate traumas and nightmares, sometimes indulging them, at others softening them with figures that blend the sensuous with the spiritual and the political with the existential.

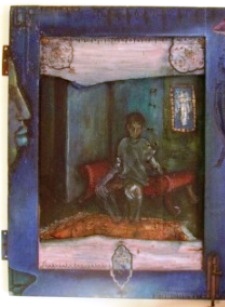

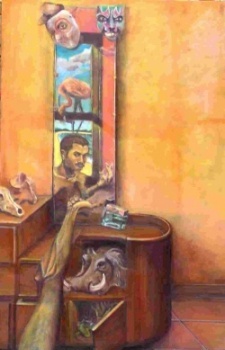

That his early works display a cracked sense of the self is not surprising. A rebel from his conventional background, Butt continues to defy the conformist meanings of family, career, security, sexuality and that elusive bourgeois pursuit of happiness. Inspired by the Stuckism movement of art, Asim holds painting as a powerful medium of communication. This standpoint brings our young Pakistani Stuckist at odds with the skin-deep novelty and claimed nihilism of “conceptual†art and postmodernism. The pursuit of art in this worldview thus merges into an impulse for a renewal of spiritual values in art and society, or what is known as “re-modernism.†In Asim’s own words:

“After the century-long assault on Beauty, an ideal obliterated by historical cataclysms such as the two World Wars and art movements reacting to them, I feel that it is perhaps time to re-imagine an Arcadia – fraught with Postmodern indeterminacy as it may be. In painting towards a new Beauty, it is not a neo-Romantic impulse of retreating into an idyll that I nurture. For art made today cannot be embarrassed of engaging the complexity of the historical moment of a globalizing multicultural society. Instead it is a tension between representing a shifting reality and an ideal beauty, or seen another way, between the social and emotional truths I experience and the tricks of illusion used to convey them that I seek to keep alive.â€

Since his return to Karachi in 2002, Asim has been both an introspective muse with bouts of self-doubt as well as a public art proponent. In 2003, he painted two murals outside the eighth century Sufi Abdullah Shah Ghazi. Not unlike the shrines of South Asia, Ghazi’s living Khanqah is a refuge for the under-class and the “scum†of the bourgeois society. The first mural, that consumed Asim like a mystic’s fire of love, was chillingly entitled, “5 Ways to Kill a Man,†and was based on the Iraq war; the second was about street children, particularly the glue-sniffing urchins with whom Asim engaged while painting the first mural. Quite symbolically, both the murals were, in due course, erased by the orthodoxy of municipal action.

Asim could very well be making up for the anguish that he feels about commercialism and isolation of “studio art†from the sociability and performativity of public art. During the forays into street narratives, the Asim we knew was undergoing a transformation. A kind of inner path that was meandering and yet achieving definition. Faced with intractable personal relationships, Asim found a direction in this public exposition of art and its magic. In 2005, the Karachi chapter of the Stuckist art movement was created by Asim.

Here was a twenty-something artist, working outside the boundaries of the hierarchy and patronage of the global art scene, in Pakistan no less. And therefore he invited a good measure of skepticism and muted resistance. This was reflected in his being banned from the Mohatta Palace Museum for one of his three interactive performative pieces which sought to claim the museum as a lived space.

Here was a twenty-something artist, working outside the boundaries of the hierarchy and patronage of the global art scene, in Pakistan no less. And therefore he invited a good measure of skepticism and muted resistance. This was reflected in his being banned from the Mohatta Palace Museum for one of his three interactive performative pieces which sought to claim the museum as a lived space.

Following his graduation from the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi in 2006, Asim has participated in various group shows across the country. By this time Asim was not the run-of-the-mill individual attempting to engineer a debut within the confines of collectors and galleries. A larger-than-art vision had taken root and it was to display itself in the tumult of 2007’s political events.

Perhaps the resistance against the imposition of emergency in November 2007 offered a moment that took Asim to another level of Stuckism. Asim led an “art protest†movement, symbolised by the “eject†signs indicating the civilian struggles for the correction of civil-military imbalances. The project involved cutting a stencil out of stiff paper and spray-painting the stencilled symbol on to whatever surface was most appropriate. He also instructed his fellow protestors on how to cut stencils and use them to paint.

Perhaps the resistance against the imposition of emergency in November 2007 offered a moment that took Asim to another level of Stuckism. Asim led an “art protest†movement, symbolised by the “eject†signs indicating the civilian struggles for the correction of civil-military imbalances. The project involved cutting a stencil out of stiff paper and spray-painting the stencilled symbol on to whatever surface was most appropriate. He also instructed his fellow protestors on how to cut stencils and use them to paint.

For those tense months of November and onwards, Karachi witnessed the number “420? repeated to create large arrows at the Supreme Court, Karachi Bench; or the “Stop†signs on torched cars and gutted banks after Benazir Bhutto’s assassination. There is a good body of temporary public art to Asim’s credit: a mural done at the San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery reacting to the US “War on Terror,†another in Mumbai, one found on the walls of The Second Floor Café, Karachi, and what he calls a “scribble†at an Akharra in Lahore.

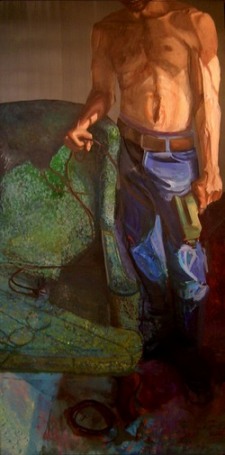

Asim’s recent art activism on the streets of Karachi, however, has not impeded his expansion as a studio artist. If anything, engagement with the political has provided further layers to the textual life of his studio art.

There is now a deeper penetration of the political into the personal, thereby detaching and undoing the existential from the hazards of nihilism. The lines are less anguished and more controlled; and the medium of oil on canvas acquires political tones conversing with the inner apparitions of the artist.

There is now a deeper penetration of the political into the personal, thereby detaching and undoing the existential from the hazards of nihilism. The lines are less anguished and more controlled; and the medium of oil on canvas acquires political tones conversing with the inner apparitions of the artist.

The problem with Asim and many others is not that they are shy of experimentation into new zones of art and existence. Their tragedy is that they live in a society that has yet to begin its search for identity; and turn the internal chaotic dynamic into a more conducive space for creativity. That said, the tremors generated by Pakistan’s fault lines also offer a near ideal arena for making a statement, both personal and political.

–Raza also edits and contributes at Pak Tea House and Lahore Nama

Many thanks for the comments here

PMA: your idea is fantastic – count me in

cheers, RR

Wasiq: This is how we do it in my opinion. Let all of us who are interested in this plan take digital images of the Pakistani art work in our custody and place these images at one web site. Then we could approach an art gallery and ask if they would be interested in organizing a live exhibition. What do you think. And if you or any one else wishes to contact me directly, ATP administration could provide you my e-mail address. We could ask Raza Rumi to by our curator!

PMA

The idea of creating a group called Collectors of Pakistani Art in America and Europe is a great one.

Count me in

Many Pak-Ams (Pakistani-Americans) have been collecting work of Pakistani artists for years. But these individual collections mostly remain unknown to the public eye. First time here at ATP I propose that we form a net work of ‘Collectors of Pakistani Art in America’ with purpose of holding exhibitions and introduction of Pakistani art in America and may be world wide. It could be done if we try. Any takers?

Hina: The fact that your friends in Pakistan could not find an art gallery in Islamabad has to do with their own limitations. There are many commercial art galleries, art studios, art colleges and museums in all major cities of Pakistan. Only recently National Art Gallery has moved into a new modern building in Islamabad. It is a nice facility with a small gift shop where some of the work could be purchased. But I agree with you there is no artists colonies or art streets in Pakistan where one could stroll from gallery to gallery or visit multiple studios at once. You just have to look. But once you get ‘connected’ it becomes easy. Most Pakistani artists are nice and polite and willing to part with their work for a reasonable price. Good luck.