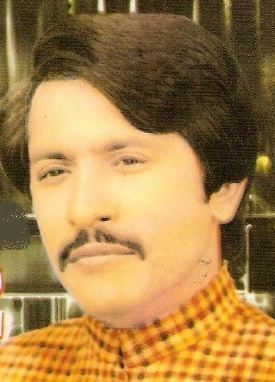

Adil Najam

Even the most ardent fans of Attaullah Khan Eesakhelvi will often under-estimate his importance in the history of Pakistan music. The importance of the Eesakhailvi phenomenon goes well beyond his songs and was central in literally changing the face of Pakistani music.

Even the most ardent fans of Attaullah Khan Eesakhelvi will often under-estimate his importance in the history of Pakistan music. The importance of the Eesakhailvi phenomenon goes well beyond his songs and was central in literally changing the face of Pakistani music.

Music has always had a central place at ATP. We have featured Shoaib Mansoor’s Anarkali, Sohail Rana’s tunes, Masood Rana’s tangay walla khair mangda, songs filmed on Waheed Murad, Runa Laila’s songs, Mehdi Hassan’s milli naghmay, the timeless melodies of Madam Noor Jahan, the qawallis of the Sabri Brothers and Aziz Mian, and more contemporary fare from Junoon, Rabbi Shergill, Rahim Shah, Strings, Jazz renditions based on Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and the multiple renditions of Bulleh Shah.

But from the very beginning I knew that I had to do a post on Eesakhailvi. And not just because I have been a huge fan of his; also because I think that even his fans do not appreciate the impact he had in launching the ‘cassette revolution’ in Pakistan.

There is rather little information on Attaullah on the Internet (Although since we originally wrote this post a wonderful fan site has been established). At one level this is rather surprising. At another level, this is typical for Attaullah Eesakhailvi.

Much of his personal life is shrouded in mystery; and myth. There have always been stories about how his music was as soulful as it was because his true love had been married to another man, that he had gone back and killed that man, landed in jail, and there – in grief and in memory – he had begun to sing. The story is nearly certainly not true. Although I suspect that there must have been a true love once.

Much of his personal life is shrouded in mystery; and myth. There have always been stories about how his music was as soulful as it was because his true love had been married to another man, that he had gone back and killed that man, landed in jail, and there – in grief and in memory – he had begun to sing. The story is nearly certainly not true. Although I suspect that there must have been a true love once.

Later, much later, he did marry – a ‘lady doctor’ is I recall – and for many diehard fans, that was what marked the end of the ‘real’ Eesakhailvi. But what I do know about him is as fantastic as this story. He became a sensation in the 1980s well before anyone heard him on television, film or radio. And that, back then, was unheard of. To become a ‘star’ you had to go through the music ‘establishment’ which was TV, film and radio, along with the music directors, poets, and producers. The way Attaullah Eesakhelvi by-passed the music establishment was by heralding a cassette revolution in Pakistan.

Recall that the 1980s was also when many of Pakistan’s rural poor found their way to ‘Dubai’ (i.e., the Middle East). Amongst the first things their new affluence brought for their loved ones in Pakistan were cassette recorders; around the same time, automobiles in Pakistan – especially including busses and trucks – started sporting cassette players. In short, the technological basis for the cassette revolution was now in place. TV, film and radio could no longer serve as ‘gate-keepers’ for musicians; and Attaullah Eesakhelvi was the very first to capitalize on this revolution.

Recall that the 1980s was also when many of Pakistan’s rural poor found their way to ‘Dubai’ (i.e., the Middle East). Amongst the first things their new affluence brought for their loved ones in Pakistan were cassette recorders; around the same time, automobiles in Pakistan – especially including busses and trucks – started sporting cassette players. In short, the technological basis for the cassette revolution was now in place. TV, film and radio could no longer serve as ‘gate-keepers’ for musicians; and Attaullah Eesakhelvi was the very first to capitalize on this revolution.

He became a sensation not because someone in the music establishment ‘discovered’ him but because his cheaply produced and cheaply priced music cassettes (or ‘kaaste’ as the word was sometimes pronounced, at least in parts of the Punjab) became immensely popular amongst bus and truck drivers – which meant that his music was soon traveling far and wide!

This was no mean achievement. Not only did he ‘create’ a whole new market, he also gave his huge clientele something that they not only wanted but which would never have passed the scrutiny of the ‘custodians’ of music in Pakistan for whom his talafuz was never really correct and his surs were never really in place. In that assessment, they may well have been correct; but it is also true that in doing what he did he also launched the cassette revolution which would later allow the likes of Nazia and Zohaib Hassan, Munni Begum, Asif Ali, and later Vital Signs to also by-pass the system. Once he became the phenomenon that he did – and once his cassettes migrated from the decks on trucks to those on limousines in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad – he was embraced by the system. He became a regular on TV and in concerts (but only quite late in his career). However, there was never a place for him on Radio till much later – he did not fit any ‘genre’; his was not ghazal, not geet, not milli naghma, and not folk music in the traditional sense either. It was honest popular music – but not ‘pop’ music since so much of it was in Seraiki. And so he had to wait until Radio was ready for him.

Some would argue that his acceptance by the ‘system’ was not good for his music. He now had to conform to the 8 minute slot, he began singing more in Urdu, he started depending on other for the music as well as the words in his songs, he worked hard (too hard) on becoming mainstream. But in doing so the very edge that had made him a phenomenon began to disappear. His sound had been the sound of the rebel – and as a rebel it did not matter if his rustic tones were slightly harsh, slightly out of tune, and slightly angry. Once embraced by the system it becomes a little difficult to remain the rebel. That is why, for some of us, the taming of the rebel was not entirely a good thing; even though it opened up his work for ever wider audiences.

Here, for old times sake, are five wonderful songs Atta Ullah Khan Eesakhelvi.

The all-time great ‘Bol Sanwal’ (an early song and an early PTV recording)

The very very popular ‘aye theeva’ (a latter song from the ‘revival’ years).

‘Dil lagaya tha dillagi kay leaye’ (an Urdu improvision)

‘Balo Batian’ (an ever-green hit, whose presentation kept changing over the years)

Finally, here is a younger Attaullah singing idhar zindagi ka janaza, in the classic Attaullah style – part qawalli, part ghazal, part bait baazi.

Note: This post was originally written and posted in December 2006.

[quote comment=”15825″]It is alleged that Eesakhelvi would sit on the ravi bridge and would take a verse written on each bus going toward the GT road. After about seven buses the poetry for his one song would complete and he would come home.[/quote]

Some thing I must mention ere

Im sure you must have heard Pakistani Stage Shows actors saying stuff like this but one thing you got to remember these actors have no respect for der own parents, sisters and other relitiv one wouldnt expect them to respect Khan shaib

Lala G was a lagend, is a legend and will remain a legend

Aim of my life is to collecet lala G’z 402 albums that have been released so far

It is alleged that Eesakhelvi would sit on the ravi bridge and would take a verse written on each bus going toward the GT road. After about seven buses the poetry for his one song would complete and he would come home.

I wa sintroduced to Essakhelvi by the bus drivers in karachi (nearly 20 years ago or more), but then somebody who worked with us moved in and brought a small cassette player and a large collection of Essakhelvi tapes. That is when I heard the ‘real’ saraiki stuff and was amazed at how many tapes he had actually released in a short time.

I brought some of his tapes with me when I moved to the US and have heard them over and over in moments when I have wondered why I was still living so far away from home. His voice has a romantic ‘dard’ to it, as others have commented, but it is a sadness that is at the same time rejuvenating and uplifting.

Where is he now and what is doing? how is his saraiki fan base holding up to the changes in his music? Once somebody in pakistan told me that when the ‘maim sahibs’ started listening to his music instead of the ‘maasis’, the speel of the crooning mesmerizer was broken.

well his a legend! but its when music is appreciated by so calle elite in apkistan then one becomes a muscian!he sang his heart ppl call him truck wala singer as he sings local poets the ones tht write their experiences that are shared by millions!he has a real voice that touches ur heart an soul! he himself says “he aint a singer” i have been to his live concerts an pvt mehfils an absolutely loathe him!later part in late 90s an now adays he has become commercial an much of his earlier music now been remixed with new videos that i guess kills the passion of the real cuisine!