(Editor’s Note: Today, January 18this the death anniversary of Saadat Hasan Manto. Two day’s ago (January 16) was the anniversary of the ‘judgement day’ in his famous ‘obscenity trial.’ To mark these anniversaries, we are re-posting this, the last of a three part series on ‘Manto ka Muqaddama,’ by Aziz Akhmad (first two parts here and here). Manto’s literary genius is always relevant, but the story of this trial is all the more relevant in these times when questions of morality, of speech and of laws are so prominent once again. We also encourage the reader to re-read this tribute to Manto, our other posts on him, and of course Manto’s own works in his own words!)

(Editor’s Note: Today, January 18this the death anniversary of Saadat Hasan Manto. Two day’s ago (January 16) was the anniversary of the ‘judgement day’ in his famous ‘obscenity trial.’ To mark these anniversaries, we are re-posting this, the last of a three part series on ‘Manto ka Muqaddama,’ by Aziz Akhmad (first two parts here and here). Manto’s literary genius is always relevant, but the story of this trial is all the more relevant in these times when questions of morality, of speech and of laws are so prominent once again. We also encourage the reader to re-read this tribute to Manto, our other posts on him, and of course Manto’s own works in his own words!)

Saadat Hasan Manto walked out of the courtroom of Sessions judge Inayatullah Khan a free man (here and here). The story Thanda Gosht was declared not obscene, and Manto’s conviction by the lower court was quashed – his sentence declared void and his fine, which Manto had already paid, ordered reimbursed.

Manto was a happy man once again. He wrote this delightful story, Zehmat-i-Mehr-i-Darakhshan, about the saga of his trial, in August 1950, which was published as foreword to the collection of stories called Thanda Gosht. Publishers, who wouldn’t publish Thanda Gosht before, started approaching Manto for the story.

Manto’s happiness, however, was short-lived. The Punjab government, not happy with the Sessions court’s judgment, went into an appeal.

The case landed with Justice Mohammad Munir of Lahore High Court (who later rose to become the chief justice of Pakistan). Justice Munir had a reputation of being a fearless, unbiased and an independent judge. However, he ruled the story obscene, re-imposed the fine on Manto, but, mercifully, waved the imprisonment sentence. He wrote an ambivalent judgment, which said, among other things, (and I am quoting from an article by Zia Mohiyuddin):

‘Leanings of the writer’ had to be taken into account and not his ‘intentions’. A story could not escape from being obscene if the details of the story were obscene. A story was not like a book, which could be good in some parts and bad in some parts.

How does one interpret this judgment?

I have read these lines several times but could not make any sense of them. The only way I can describe this judgment is by resorting to an American slang, actually Texan, which may not be quite as elegant but very expressive: Justice Munir is “trying to pee down both legs”.

It seems Pakistan owes more than just ‘doctrine of necessity’ to Justice Munir.

Manto lived another 4 years to write numerous stories and short pieces, including his most famous Toba Tek Singh. He died shortly before reaching his 43rd birthday, on 18 January 1955, in extreme poverty and broken hearted.

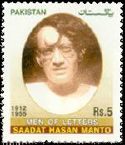

Manto has been described as one of the greatest short-story writers of South Asia, but Pakistani establishment never owned him. However, on his 50th death anniversary, in 2005, the government officially recognized Manto by issuing a commemorative postage stamp in the series of stamps called Writers of Pakistan.

Manto has been described as one of the greatest short-story writers of South Asia, but Pakistani establishment never owned him. However, on his 50th death anniversary, in 2005, the government officially recognized Manto by issuing a commemorative postage stamp in the series of stamps called Writers of Pakistan.

Technically, Justice Munir’s judgment on Thanda Gosht still stands, but practically there is no ban on the story, today, in Pakistan, and it is freely printed and sold along with Manto’s other works.

It would be interesting to see what would happen if someone petitioned the Supreme Court today to overturn Justice Munir’s judgment on Thanda Gosht or else ban the story. I was told, Aitzaz Ahsan has the record of this court case and is amply qualified to petition the Court. Perhaps, ATP could petition Mr. Ahsan to take up this case with the Supreme Court.

Now, back to the title, Zehmat-i-mehr-i-darakhshan. It is a phrase from a couplet of Ghalib. Here is the couplet first, then a translation by Khalid Hasan, then meanings of difficult words and, finally, an explantion.

Larazta hai mera dil, zehmat-i-mehr-i-darkhshaN par

Main hooN woh qatra-e-shabnam, keh ho khaar-i-bayabaN par

I am like a drop of dew that rests on a thorn in the wild;

My heart trembles at the thought of the sun that will (soon) rise (and annihilate me.)

darakhshaN = Brilliant light, sunlight

mehr = The sun, favor, kindness

zehmat = trouble, pain, uneasiness of mind

khaar-i-bayabaaN = thorn bush in the wild

Normally, the morning sun brings new life, hope and a new beginning in a person’s life. But for a drop of dew in the wild, the morning sunshine heralds its death, for the moment the sun comes up, the dew evaporates. This is how Manto saw his daily life. Every new day brought new worries, new trials and tribulation.

Earlier Parts of This Post can be Read at:

1. Manto ka muqaddama: Obscentiy Trial Part I

2. Manto ka muqaddama: Obscentiy Trial Part II

“Perhaps, ATP could petition Mr. Ahsan to take up this case with the Supreme Court.”

I don’t think this would be a good idea. Given that the books are being sold freely, it seems that this issue is not on the extremist radar; the only thing such a case would do is open up booksellers to attack. One can only imagine what would happen if mullahs started combing through bookstores to look for disapproving material.

Timely topic. This whole idea of having courts decide on questions of morality (Manto) or religion (Blasphemy) is itself ridiculous and the root of too much evil.

Justice Munir did a good decision… Interesting article.

@Naan Haleem.

I why you made it a point to read ALL of Manto’s work. Was it because you were looking for a sexuality kick?

On a more serious note, sexuality is a natural and necessary part of the human psyche. The abnormal behavior is of those who do not talk about it or suppress their frustrations and then sneak to watch porn over internet or in dark rooms. Also, sexuality (I assume you did not mean ‘sexist’ since that means something else) is in the readers mind. Frustrated people will get ‘shehwat’ from watching daily TV ads, the cure for these sexual frustration lies with the reader, not the writer.

I have read most of the Manto’s stories and without any bias for or against him.

Believers in Manto claim that his stories are social with a touch of sex. But with the frequency and details of sex in his stories, I would describe them as “sexist with a touch of societal injustice”. How could a writer incorporate sex in each and every piece of work without having a sexist mind?

This opinion is about his work and not the trial(s).