Adil Najam

I am most pleasantly surprised that readers have so quickly figured out the mystery man in our latest ATP Quiz. Since they have, let me add a little more information and let the discussion continue.

I am not sure, however, how many readers know of Muhammad Asad or of his connection to Pakistan. Let me confess that until fairly recently I did not; at least not of the Pakistan connection. As I have gotten to know more about this connection, I have gotten more and more intrigued – all the more so because there is relatively little in his own writings or that of others about this.

But lets start from the beginning.

Asad was born in 1900 as Leopold Weiss to Jewish parents in Lvov (then part of the Habsburg Empire, now in Ukraine). He moved to Berlin in 1920 to become a journalist and traveled to Palestine in 1922. It was there that he first came into contact with Arabs and Muslims and began a long journey into Muslim lands and minds that eventually led to his embracing Islam in 1926. His bestselling autobiography Road to Mecca (published 1954) recounts these years in vivid and captivating detail., including his adventures in Arabia and in working with King Ibn Saud and the Grand Sanusi, amongst others.

Asad was born in 1900 as Leopold Weiss to Jewish parents in Lvov (then part of the Habsburg Empire, now in Ukraine). He moved to Berlin in 1920 to become a journalist and traveled to Palestine in 1922. It was there that he first came into contact with Arabs and Muslims and began a long journey into Muslim lands and minds that eventually led to his embracing Islam in 1926. His bestselling autobiography Road to Mecca (published 1954) recounts these years in vivid and captivating detail., including his adventures in Arabia and in working with King Ibn Saud and the Grand Sanusi, amongst others.

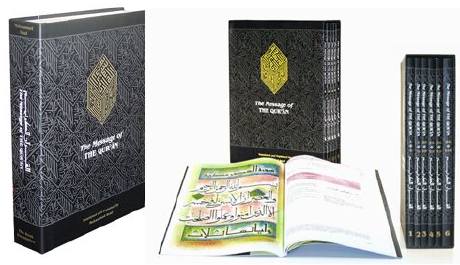

Later in his life, after retiring in Spain, he spent 17 years working on an English translation of the Quran which was first published in 1980. Many consider this to be one of the finest English translation of the Quran – some argue this is because he himself was fluent in bedouin Arabic which is closest to the Arabic in the Quran, others suggest that since he was himself a European and wrote in more understandable idiomatic English his translation is most accessible to non-Arabic speakers.

As a lay-reader who ver the years has read a number of English translations, including his, I do find Asad’s translation – The Message of the Quran – to be easier to read than those by Abdullah Yusuf Ali or Marmaduke Pickthall which are amore formal and literal translations. Unlike the translations by Prof. Ahmed Ali (my particular favorite) and by Thomas Cleary which are also in contemporary idiom and very readable, the Mohammad Asad translation has the added virtue of also having commentary and explanations, and the new edition is wonderfully presented, printed in the highest quality, and with tasteful calligraphy. All in all, Mohammad Asad’s The Message of the Quran is the translation that I now recommend to friends, Muslims as well as non-Muslims.

But I digress. Much as I like Muhammad Asad’s translation of the Quran and especially in its new printing, that is not the subject of this post. The subject of the post is his ‘Pakistani connection’ and also why we do not find much about that connection in his writings. Here is what we know.

By the early 1930s Asad had gotten rather disenchanted by King Ibn Saud and his religious advisors (see Road to Mecca) and had begun travelling Eastwards into other Muslim lands. This brought him to British India and there he met and became a good friend of Dr. Mohammad Iqbal. Indeed, Iqbal encouraged him to write his book Islam at the Crossroads (published 1934); whose cover has the following testimonial from Iqbal:

“I have no doubt that coming as it does from a highly cultured European convert to Islam, it will prove an eye-opener to our younger generation.” Muhammad Iqbal.

During World War II imprisoned him in a camp for enemy aliens (because of his Austrian nationality) while his father was interned by the Nazis because he was Jewish. After the War he fervently threw his all behind the demand for Pakistan. Upon the creation of Pakistan, he saw himself very much a ‘Pakistani’ as did those he worked with (reportedly even took to wearing the achkan). In 1947 he became the director of the Department of Islamic Reconstruction in West Pakistan and worked on a treatise with ideas for the Constitution of Pakistan. Many of these ideas (which were mostly related to creating a multi-party parliamentary democracy) were reproduced in his later books but he was not very successful in getting them implemented.

In 1949 Asad joined the Pakistan Foreign Ministry as head of the Middle East Division and eventually in 1952 came to New York as Pakistan’s representative to the United Nations. Here he met the woman who would become the last of his wifes (Pola Hamida). Whether it was the fact that he married her and divorced his earlier wife or the messiness of Pakistani politics, it was in this period that he fell out with the powers in Pakistan and resigned from the Foreign Ministry. He decided to stay on in New York to write Road to Mecca, which became a major success. He never really returned to Pakistan (although, supposedly, Gen. Zia ul Haq tried to get him back) and died in Europe in 1992.

In 1949 Asad joined the Pakistan Foreign Ministry as head of the Middle East Division and eventually in 1952 came to New York as Pakistan’s representative to the United Nations. Here he met the woman who would become the last of his wifes (Pola Hamida). Whether it was the fact that he married her and divorced his earlier wife or the messiness of Pakistani politics, it was in this period that he fell out with the powers in Pakistan and resigned from the Foreign Ministry. He decided to stay on in New York to write Road to Mecca, which became a major success. He never really returned to Pakistan (although, supposedly, Gen. Zia ul Haq tried to get him back) and died in Europe in 1992.

It was his estrangement with the Pakistan government that pushed him back into writing and produced two amazing works – Road to Mecca and The Message of the Quran. However, here once again is a story of one who wished to give his all to Pakistan and we did not let him.

I have not read his translation of the Quran, but I have read ROAD TO MECCA and it is one of the most inspiring books I have ever read. I have reccomended it to many many friends.

Adnan,

I could not acknowledge Pickthall as the post was about Asad and since he was deeply involved in the idealogical redirection of future of Pakistan, I had to stay focus on him. Pickthall’s contributions are indeed very worthy and significant. Thanks.

PatExpat, you are certainly right in as much as Muhammad Asad’s vision for Pakistan was of a model modern Islamic state. This was to be his Utopia, the one he had failed to find in Saudi Arabia (ref. ‘Road to Mecca’). But that also meant that his vision was not the same as that of Jinnah or that of the majority of the leaders of the Muslim League. His was very much a minority viewpoint.

The tragedy for him was that he was as minority within a minority. Those who at that time (or now) also wanted an Islamic state had a VERY different idea of what that state should be like. For Asad, it was a to be a modern, democratic, multi-party, and what we would today call a liberal Islamic state (he would clearly be against the clerics at Lal Mosque, Ref. ‘Islam at the Crossroads’). Note from his book ‘State and Government in Islam’ that he thought that such a state was not only possible but was the only true Islamic state. That is where he and others in the religious group parted ways. His vision, which flowed from Iqbal’s, of a revived and reformed Islamic state was then not in favor amongst the religious leadership of Pakistan. It still is not.

But all of that is less important. The striking thing about those very early years was that you COULD intellectually discuss tricky issues such as what is an ideal Islamic state without the believers resorting to violence or liberals resorting to slogans. Note that the department he headed in 1947 was called the Department of ISLAMIC RECONSTRUCTION. Do we think a department named like this could even exist today without someone burning its office down. And what if someone wrote a book called ‘RECONSTRUCTION OF RELIGIOUS THOUGHT IN ISLAM.’ Would a book with that title not be banned immediately? As my previous message mentioned, this intellectual freedom vanished very soon and the defamation campaign against Asad by the religious extreme was an early example of what would follow.

Part of me is glad you brought up this great man. Part of me is very concerned that we are going to drag the poor guy through muck again. That is what we did to him the last time.

Mohammad Asad was very close to Iqbal and if you read his ‘Islam at Crossroads’ it is in the spirit of Iqbal’s ‘Reconstruction of Islamic Thought.’ For him Pakistan WAS an experiment to see if a liberal and democratic Islamic state was possible. That made him slightly distant from Jinnah, who Asad saw as too secular, but it made him even more distant from people like Mawdudi who was forwarding a very different vision of the Islamic state from Asad. Both Mawdudi and Asad were contemporaries working on concepts of the ‘Islamic State’. Asad’s great book on this is ‘State and Government in Islam’ which you refer here. If you read it you will find that his view of the Islamic state was very different from Mwdudis, specially in terms of multi-party democracy and parliamentary supremacy. It was also different from Jinnah’s but less so. The roots of Asad’s vision of Islam (which was much more like Iqbal’s) are found in his book ‘Road to Mecca’ where he discusses Abdul Wahab and how his teachings had stifled teh progressive tendencies within Islam. It is that thinking that made him close to Iqbal and distant from Mawdudi. Ultimately, one had to accept that Asad’s vision of what the Islamic state should be lost and Mawdudiat won in Pakistan.

But had it just been an intellectual debate as Asad thought it was then it would be OK. Unfortunately, the right wing in Pakistan did to him what the right wing always does – it began a nasty smear campaign against him [just like Maulana Dick Cheney is doing in the US against his opponents, but also like what the maulvis did to Edhi, or to Abdus Salam, or even Jinnah]. From the earliest days a campaign was launched against him because of his Jewish heritage, he was labeled a European agent, and ultimately it was his marriage to an American woman (who also converted to Islam) that gave his opponents the opportunity that forced him to resign (much like what is happening to the woman minister who parachuted in France recently). Ultimately, he had too much dignity to indulge in dirty fighting with the religious establishment in Pakistan and decided to retire abroad. As you say, maybe that was good because without it maybe his greatest works would never have been completed.

He became the target of the smear campaigns because his goal, like Iqbal’s, was Islamic rennaisance and his struggle was against static extremism. For example, look at this quote, “”The great mistake is that most of these leaders start with the hudud, criminal punishment. This is the end result of the sharia (Islamic Law), not the beginning. The beginning is the rights of the people. There is no punishment in Islam which has no corresponding right.” Or this one, ” “The door of ijtihad will always remain open, because no one has the authority to close it.”

His book ‘Road to Mecca’ is clearly his most famous and captivating book which I recommend to everyone. But for anyone really interested in serious thinking about what a truly Islamic but non-fundamentalist and non-Taliban state would look like, I would suggest reading his ‘State and Government in Islam’ and also ‘Islam at Crossroads.’

Dear Anwar you forgot William Pickthall.