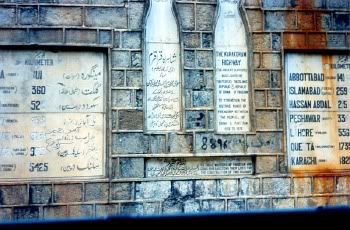

The souls that pave the way for the modern tarmac road known as the Karakorum Highway (KKH) still seem to flicker amongst the sharp moving shadows of the unstable rocks and the almost countless but crumbly semi-transparent glaciers that constantly threaten its existence.

The souls that pave the way for the modern tarmac road known as the Karakorum Highway (KKH) still seem to flicker amongst the sharp moving shadows of the unstable rocks and the almost countless but crumbly semi-transparent glaciers that constantly threaten its existence.

There has always been a long pass into, and out of China over what is sometime called the “Roof of the World” but in ancient times it was a very hazardous passageway. One wonders how Alexander might have crossed the Karakorum Mountains in 325 BC or how early travellers like Marco Polo, Hieun Tsang and others might have tracked on the route without backpacks, four wheel driven powerful vehicles and even the roads, till Pakistan Army engineers spread asphalt through one of the most difficult terrain in the world and created this great engineering feat that some call the eighth wonder of the world.

Northern Pakistan has some of the most beautiful and mightiest mountain terrain — Hindu Kush and Karakorum — in the world. Besides raw natural beauty, the territory is very difficult for men and machine to work even in this modern age. The road is in fact reflection of man’s incessant struggle against transcendental power.

What one sees while commuting on the highway? A quote from the North West Frontier Province Gazetteer reads:

What one sees while commuting on the highway? A quote from the North West Frontier Province Gazetteer reads:

“the path is certainly narrow, and often clung to the sheer faces of the many deep resonant gorges that confine their turgid, animated rivers. A traveller along the path sees at one glance the shadowy valleys from which a shiny mist columns rise at noon against a luminous sky, the forest ridges, stretches fold behind fold in softly undulating lines — dotted by the white specks which mark the situation of Buddhist monasteries — to the glacier draped pinnacles and precipices of the snowy range. He passes from the zone of tree ferns and endless colonnade of tall stemmed magnolias oaks and chestnut trees, fringes with delicate orchids and festooned by long convolvuluses to the region of gigantic pines, junipers, firs and larches. Down each ravine sparkles a brimming torrent, making the ferns and flowers nod as it dashes past them. Superb butterflies, black and blue, or flashes of rainbow colours that turn at pleasure into exact imitation of dead leaves, the fairies of this lavish transformation scene of nature, sail in and out between the sun light and gloom. The mountaineer pushes on by a track half buried between the red twisted stems of tree-rhododendrons, hung with long waiving lichens, till he emerges at last on open sky and the upper pastures — the Alps of the Himalayan – field of flowers: of gentians and edelweiss and poppies, which blossom beneath the shining store house of snow that encompass the ice mailed and flouted shoulders of the giants of the range.”

Get off the Grand Trunk Road — main artery of Pakistan — near Hassan Abdal; travel northeast through plains of Hazara and you are already in tourists’ zone. Cyclists riding trendy machines and cellular phones even with local are commonly seen and almost all commodity items for the use of foreigners are available with vendors right on the roadside. Lucky ones may also have the pleasure to watch performance of Chinese artists at Silk Rout Festival that moves from place to place and gives spectacular performance.

Passing through outskirts of Mansehra, the road starts winding and climbing through forested hills, with houses climbing to the contours of hills and countless eateries lined up along the road. The travellers here are introduced to forbidding nature of the terrain. The River Indus gushes below and cliffs of bar rocks soar above as the KKH begins to cut its way through the gorges of Kohistan. After dipping into, and out of the Indus’s wide bed the road also seem vying for the right of way with Gilgit and Hunza Rivers before it heeds direct to the historic Khunjerab Pass into China. Voluminous traffic and rather unpleasant riding conditions becomes lighter after leaving Mansehra and remains so almost to Khunjerab Pass and beyond (to the end of the highway in Kashgar, China.)

Passing through outskirts of Mansehra, the road starts winding and climbing through forested hills, with houses climbing to the contours of hills and countless eateries lined up along the road. The travellers here are introduced to forbidding nature of the terrain. The River Indus gushes below and cliffs of bar rocks soar above as the KKH begins to cut its way through the gorges of Kohistan. After dipping into, and out of the Indus’s wide bed the road also seem vying for the right of way with Gilgit and Hunza Rivers before it heeds direct to the historic Khunjerab Pass into China. Voluminous traffic and rather unpleasant riding conditions becomes lighter after leaving Mansehra and remains so almost to Khunjerab Pass and beyond (to the end of the highway in Kashgar, China.)

Before crossing on the Chinese side of the Khunjerab Pass, the road passes through Hunza Valley. The intricate terraced fields, held in places by dry stone or wooden retaining walls and the complex system of irrigation channels leading down from mount Rakaposi or Ultar are testimony to the skilled labour of the locals who are famous for their different culture, friendly nature and long lives. While the entire Hunza Valley is breathtaking in its splendour and beauty, one of my most enduring memories of this place is watching the sunrise over the hills. And, when you devote enough time to look at the mountains, it becomes a bit chameleon — clouding over, changing colours, cliffs turning into convex and concave according to the slant light.

At night, lights glow in this tiny isolated villages. But, the village women still do not know the use of simple electric appliances of modern age. Community hydroelectric system has been installed on torrents. The system allows only few bulbs per household. Men and women are found working together in the fields, homes or collecting woods from hills in conical wicker baskets. They are welcoming and seem to be living at peace with themselves.

The highway is also called the “Silk Road” because it approximates the trail of what was once one of the many silk, jade and spice carrying caravan trails that congregated somewhere near Xi’an, in China, and terminated in the vicinity of modern Syria on the Mediterranean sea coast. Like long lines of exploring ants, determined traders, merchants and adventures wore a path through narrow gorges, high grass sheathed valleys, across waterless deserts, around higher mountains, and over ranging rivers in pursuit of bargains.

The highway is also called the “Silk Road” because it approximates the trail of what was once one of the many silk, jade and spice carrying caravan trails that congregated somewhere near Xi’an, in China, and terminated in the vicinity of modern Syria on the Mediterranean sea coast. Like long lines of exploring ants, determined traders, merchants and adventures wore a path through narrow gorges, high grass sheathed valleys, across waterless deserts, around higher mountains, and over ranging rivers in pursuit of bargains.

The passage of time has not altered any of these geophysical conditions. Rest every thing in the area has changed though. The developments found their is greatest physical manifestation with the construction of the KKH, built along the path of the caravan routes of the Silk Road, a joint venture between China and Pakistan (which is why it is also called as Pakistan-China Friendship Road). Work on the mammoth project, which is said to have cost one life for every kilometre of road constructed, was begun in 1966 and completed in 1982. With commissioning of the road, the entire area has been laid open to trade and tourism. The resulting progress is undoubtedly causing a great deal of visible societal change.

While regular bus service ply the KKH to Gilgit, Hunza and the Khunjerab Pass, and the route eastwards through the Indus gorge to Baltistan, four-wheel drive powerful vehicles can only negotiate many of the remaining roads dissecting the region. There are lots of rough tracks leading to off road habitats on both sides of the road. For the adventurer who wants to go beyond these to really explore the mountains there is a highly developed system of trails built up over thousand of years by the tradesman, nomads and herdsmen, all granting access to some of the most magnificent mountain scenery on earth.

S A J Shirazi is a Lahore (Pakistan) based writer. (See more at Shirazi’s blog ‘Light Within’).

Simply exilarating! Thank you so much!

Happen to see now your blog Shirazi,

well done,its a dream for those who believe in dreams, I went

uptill Naran thats it. Wish to go on that paradisiac crazy route.