Adil Najam

As the fourth part of our series on the events of 1971, we are reposting this post which was first published at ATP on December 16, 2006. We are reposting it with all the original comments since they, as a whole, are very much part of the conversation we all need to have with ourselves. The previous three parts of the series can be read here, here and here.

As the fourth part of our series on the events of 1971, we are reposting this post which was first published at ATP on December 16, 2006. We are reposting it with all the original comments since they, as a whole, are very much part of the conversation we all need to have with ourselves. The previous three parts of the series can be read here, here and here.

Today is December 16.

Today Bangladesh will mark its 35th ‘Victory Day.’

Most Pakistanis will go about their lives, not remembering or not wanting to remember. We should remember – and learn – from the significance of this date.

Most Pakistanis will go about their lives, not remembering or not wanting to remember. We should remember – and learn – from the significance of this date.

Not because it marks a ‘defeat’ but because it marks the end of a dream, 24 years of mistakes, horrible bloodshed, traumatic agony, and shameful atrocities. The constructed mythologies of what happened, why, and who is to be blamed need to be questioned. Tough questions have to be asked. And unpleasant answers have to be braced for. We need to honestly confront our own history, for our own sake.

But right now, the goal of this post is different. We at ATP just wish to extend a hand of friendship to our Bangladeshi friends. May the memories we make in our future be very different (and more pleasant) than the scars we carry from our past.

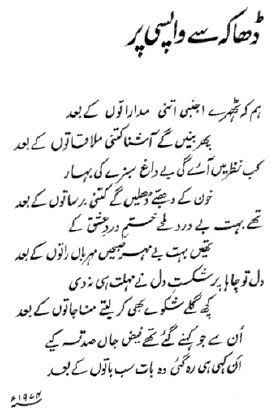

There is much – too much – that I wish to say; but cannot find words for. So let me do what I always do when I am at a loss of words. Let me quote Faiz Ahmad Faiz, who in his memorable 1974 poem ‘Dhaka say wapsi par’ (On Return from Dhaka) expressed what I wish to say so much better than I ever could.

We share with you here the original poem in Urdu, a version in ‘Roman Urdu,’ a wonderful English translation of the poem by the late Agha Shahid Ali in his book The Rebel’s Silhouette, and a video of Nayarra Noor singing the verses with the passion and feeling that they deserve.

ham ke Thehre ajnabi itni mulaaqaatoN ke baad

phir baneiN ge aashna kitni madaaraatoN ke baadkab nazar meiN aaye gi be daaGh sabze ki bahaar

khoon ke dhabe dhuleiN ge kitni barsaatoN ke baadthe bahut bedard lamhe khat’m-e-dard-e-ishq ke

theiN bahut bemeh’r subheiN meh’rbaaN raatoN ke baaddil to chaaha par shikast-e-dil ne moh’lat hi na di

kuchh gile shikwe bhi kar lete manaajaatoN ke baadun se jo kehne gaye the “Faiz” jaaN sadqe kiye

an kahi hi reh gayi woh baat sab baatoN ke baad

Agha Shahid Ali’s Translation:

After those many encounters, that easy intimacy,

. we are strangers now —

After how many meetings will we be that close again?When will we again see a spring of unstained green?

After how many monsoons will the blood be washed

. from the branches?So relentless was the end of love, so heartless —

After the nights of tenderness, the dawns were pitiless,

. so pitiless.And so crushed was the heart that though it wished

. it found no chance —

after the entreaties, after the despair — for us to

. quarrel once again as old friends.Faiz, what you’d gone to say, ready to offer everything,

. even your life —

those healing words remained unspoken after all else had

. been said.

Urdu was the uniting factor for all the muslims and it was fair to say that none of the regional languages were made into national language to avoid regional differences… however, another way to go about this could have been to make east pakistan bilingual….. just like the provice of quebec in canada

First, I really do NOT want to make this about Mohajir or Punjabi or Pathan. Remember, it was exactly that type of thinking that got us where we got on Bangladesh. My point only is that there is plenty of blame to go around and everyone – I mean EVERYONE – had a hand in this.

Adnan, you are exactly right. None of those people were Muhajirs. But by the time they came on the scene, East Pakistan had already been lost for at least 10 years or more. Both Ayub and Yahya, and some extent Bhutto (two Pathans and a Sindhi) hastened the processes. Personally, I think if one person has more of the blame than anyone else it is Ayub, who sealed the case (which is why I find it funny when people think he was good for Pakistan).

What I was referring to with Karachi as capital and the Mohajir (not ordinary people but the early govt. and bureaucracy in Pakistan which was nearly entirely immigrants post-partition), was the events of the late 40s and early 50s. Which is when the national language issue was fought and which is when the disenchantment of the East Pakistanis set in because of (a) the way they language was ridiculed in the debate, and (b) how Bengali politicians (especially Suhrawardhy) were side-lined by Liaquat Ali and others (even called traitors).

As I said, you cannot understand Bangladesh as a simple 1971 event. You have to go back at least to 1947 and you find that certainly by 1954-55 (when the United Front wins and then is removed) Bangladesh had become inevitable. Then it was a matter of time and it took Ayub and Yahya to put the final nails on it.

Two interesting things about history. One, single causes for anything is nearly never correct. Two, it cannot be understood only by looking at one moment, it was to be understood full.

Looking at Mujib’s six points is important in understanding the events of 1971 but if we want to understand the separation of East Pakistan we have to look much deeper and the six-points tell only a small part of the story. The story had already ended by then, at least for 15 years. We find it easy to look only at six-points and 1971 because it is convenient for us and we can pass the blame to the ‘usual suspects’… i.e., it was the Army, or it was the Punjabis or it was Mujeeb (it was anyone, except us!).

The fact is that the language issue is what ‘created’ Bangladesh. After that it was just a question of time and leaders (especially Liaquat and later Ayub only kept making things worse and hastening the process). The imposition of Urdu (I say this as a ‘Urdu speaking Mohajir’) was the defining issue that convinced Bengalis that this was not going to work and the West Pakistanis (at that point the leadership was Karachi-based mostly ‘Mohajirs’) was not going to accept them as equals. It was to East Pakistan was the 1937 elections were to Muslims in India (which convinced Muslims that their rights were not going to be respected in an India-wide system).

One can argue whether the decision was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, but that is irrelevant. The important point is that early on Pakistan had to make a decision and it made a decision that sent a message to the majority of its people that their interests were not going to be accepted. Also, lets be honest, Urdu was a NEW and UNKNOWN language to MORE Pakistanis in the 1950s than, say, Bengali would have been (not only Bengalis, but most of what became Pakistan did not speak Urdu). IT is too late now, but the experience suggests that just like people who did not speak Urdu took it up, so people could also have taken up Bengali. More importantly, if you go back to the documents of the time you find that the options were NOT Urdu v. Bengali only. There were other ways (like, truly, joint national languages; which was tried later, but it was too late). For example, had English or even Urdu been made national language and all local languages given much more serious attention and respect (instead of forcefully trying to suppress them) things could have been different.

We turned the battle into a war between the language of Ghalib and the language of Tagore. It was a tragic and useless battle, made worse because we believed the two could not prosper together. Had we given each a chance, maybe the West Pakistanis would not have developed the sense of superiority and arrogance that eventually led to the horrific inhumanities.

The more I listen to this song the more I love it, both the poetry and how it is sung. Is there anyway to put this on my hard disk so that I do not have to be connected to listen to it.

[quote post=”471″]First is the role to Urdu in flaring Bengali nationalism. Qaid-e-Azam, against the advice of Sir Agaha Kahn decided to make Urdu as a national language. Under democratic principles,Bengali could have easily become the national language.[/quote]

I agree with every point raised by EP people at that time but not this urdu one. Being in majority dosn’t mean that a regional language should be imposed on a country. When we say a natiional language, it means that everyone could understand it without any particular region influence therefore choosing Urdu as a national language was not a wrong decision at all. By national language doesn’t mean you can’t speak in local lanugage. Pakistan’s national language is Urdu but majority speaks Punjabi. Urdu didn’t damage their regional image.

Arabic was also not a good choice because majority of muslims in 19th century were not used to speak Arabic like their forefathers who migratted from Iraq and other arabic countries plus converted muslims had no arabic background therefore Arabic was like an outsider language for them and couldn’t gain any popularity plus non-muslim Pakistanis could reject to accept a language which have religious influence.