She is not the grave-visiting sort. A white-haired dynamo with luminous eyes, she pioneered teacher training and teaching English in Pakistan (as a second language in large classrooms with limited resources). The activism inculcated in her native Pratapgarh in UP, India, remained with her after the migration to Pakistan in the late 1950s, later nurtured and encouraged by the life partner she found.

Zakia met Sarwar after moving from Lahore to Karachi in 1961. The unconventional, long-limbed Allahabad-born doctor was known as the ‘hero of the January movement’. Visiting Karachi for a holiday after Partition he had stayed on after being admitted to Dow Medical College.

There, he started Pakistan’s first student union in 1951, catalysing the first nationwide inter-collegiate students’ body. When the government ignored the students’ demands (including lower fees, better lab and hostel facilities and a full-fledged university campus) the students held a ‘Demands Day’ procession on January 7, 1953. Police brutally baton-charged and tear-gassed them, and arrested their leaders. They were set free hours later under pressure from students staging a sit-down in front of the education minister’s house, refusing to budge until their release.

The momentum continued with another procession on Jan 8. This time, they were confronted by armed police. Trying to negotiate with the police to let them pass Sarwar realised that their threat of opening fire was deadly earnest, he tried to stop the students from going forward. Charged up, many surged ahead anyway. The police opened fire. Seven students and a child were killed on that ‘Black Day’. Over 150, including Sarwar, were injured.

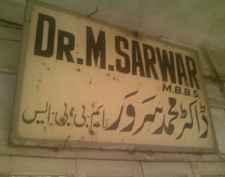

The college principal Col. Malik visited the family to get them to persuade Sarwar to give up his activism. The support of Akhtar, his even taller older brother, a well known journalist, gave him the courage to resist. Both were jailed during the crackdown on progressive forces coinciding with America’s McCarthy years, after Pakistan and America signed a military pact (Sarwar received his final MBBS results in 1954 while in prison for a year).

The January Movement’s impact can be gauged by the Khawaja Nazimuddin government’s eventual acceptance of most of the students’ demands. The students were even asked to approve the blueprints of Karachi University (based on Mexico University). In the 1954 provincial elections it was a student leader defeated the seasoned politician Noor-ul-Amin in former East Pakistan.

After graduating from medical college, Sarwar declined invitations from various politicians to join their parties. “I didn’t have the means,†he said simply. He was the sole breadwinner of the family after Akhtar’s sudden death due to pneumonia in 1958 at the peak of his career – he was chief reporter of the newly launched eveninger The Leader. Their circle of progressive writers, poets, activists and journalists was devastated. The well known poet Ibne Insha compiled a book of essays on Akhtar (including by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Hameed Akhtar and others) and his letters from prison. Sarwar, who had been particularly close to Akhtar, insisted that everyone get on with their work and not sit around mourning.

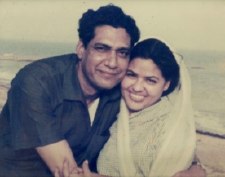

Zakia’s older brother Zawwar Hasan had been one of Akhtar’s closest friends. They had played field hockey for rival college teams in Allahabad, re-connecting as sports journalists in Karachi. After moving to Karachi, Zakia, who began teaching at Sir Syed Girls College there, would take Zawwar’s young children to Sarwar’s clinic nearby for checkups. The romance included outings like seeing off the Faiz sahib when he left for Moscow to receive the Lenin Peace Prize in 1962.

“As a comrade, his relationship with Abba was an unspoken clear bond based on a shared understanding of the universal struggle for a just human order,†says Salima Hashmi, Faiz’s daughter and an old friend of Zakia’s from her Lahore days.

Sarwar and Zakia got married in September 1962, overcoming parental apprehensions about religious differences (Shi’a, Sunni). Neither was religious. Akhtar would have approved, as Zawwar did.

As their eldest child, one of my earliest memories is Zakia and other college teachers on hunger strike, demanding an end to the exploitation of teachers. Sarwar supported her against the muttered disapproval (‘women from good families out on the streets’), as always, giving her the space to develop her potential. No wonder that he has a special place in the hearts of her colleagues at Spelt, the Society of English Language Teachers that she founded, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year.

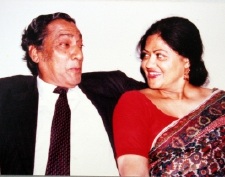

Sarwar practiced as a general physician for nearly fifty years from his modest clinic in a low-income area, consciously charging low fees and treating struggling workers, journalists, artists and writers for free. He was contemptuous of doctors who charged high fees, prescribing costly tests and medicines where less expensive ones would do. He helped launch the Pakistan Medical Association and its affiliated Medical Gazette – both of which have been vital platforms for progressive politics in Pakistan, particularly during the Zia years.

Diagnosed with cancer in August 2007 (‘stage four’, pancreas, metastasis to the lungs), he took it in stride. “Look,†he reasoned in his remained characteristically calm and good humoured way, “everyone has to die. If this is how I have to go, so be it.â€

He refused to give up drinking or smoking, reminding us of friends who died early despite giving up such habits. When a cousin’s mother-in-law was diagnosed with lung cancer, he asked wryly, “And does she also smoke?â€

“To look into the eyes of a killer disease, and yet not roll over is something that the bravest could envy,†wrote Zawwar last October from the Bay Area.

Sarwar defied doctors’ predictions of ‘maybe six months…’, humouring us by trying the nasty herbal concoctions we inflicted on him, and later stoically withstanding six months of chemotherapy at SIUT, the pioneering philanthropic institution set up by his old friend Dr Adibul Hasan Rizvi. Perhaps this bought him some more time. Perhaps it was simply the sheer willpower of a fighting spirit refusing to give up hope even while realistically facing the worst.

Friends flocked to ‘Doc’, as many affectionately called him, hosting parties at his home when he was too weak to go out.

Emerging from anaesthesia after a blocked bile duct was cleared this April, one of his first questions was about the Indian elections. He’d ask for the daily newspapers – even when weakness made difficult to concentrate – and that cigarette which one of us would light. He’d chat hospitably with visitors, cigarette dangling habitually between the fingers of one hand even as a drip punctured the veins of the other arm.

At home later, it was only during the last two days of his life, his breathing dangerously obstructed, that he did not smoke. Doctors suggested suctioning out excess fluid in intensive care – entailing drips (no space for more needle pricks in either arm by now) and the risk of life support if the procedure failed. When I explained this to him, he waved his hand and pronounced, ‘No point, no point’. They sent over technicians with an inhaler and suction pipe, which gave him some relief. But then the rattling in his throat recurred.

Late that night, when he seemed to be more comfortable and settled, I finally said goodnight, kissing him on the forehead. “Sleep well Babba.â€

“Goodnight,†he replied, clasping my hand back. “Go to sleep.â€

He died quietly in his sleep about half an hour later.

Zakia now takes time out from her work to sit by his last resting place. It gives her peace.

Beena Sarwar is a journalist, a documentary filmmaker, and Dr. Muhammad Sarwar’s eldest child. Versions of this essay have also appeared at the Dr. Sarwar website, The News, and HardNews.

Although I met him only one time at his him, as Madam Zakia Sarwar students. I listened to several stories of from Madam, wherever Zakia aapa discuss him, I easily feel proudness in her words. May Allah blesses Dr. Sarwar.

A graceful personality. Tall & handsome. That is how I remember him.

A family friend from my mom’s side he was also our physician.

The seeds sown by him and other activists continue to blossom and let’s hope

کہ وہ صبح کبھی تو آے گی

MAQDOOR HO TUO KHAK SAY POCHOO KEH AIE LAYEM

TUO NAY JO GANJ HAYAE GERA MAYA KYA KEA

(If I was fortunate enough, I would ask the earth, Oh! Miser,

What did you do with those priceless treasures?) — Ghalib

May his soul rest in peace!

Very moving article ,keep it up .That generation of upright people is fading away,we should all learn from them.