Lahore’s eclectic past was dazzling. Prior to the partition of India, it was a cosmopolitan centre and later retained its primacy as Pakistan’s cultural capital though it lost its inclusive atmosphere. This is a city where Bapsi Sidhwa’s characters lived, Allama Iqbal wrote and recited his high-poetry and Amrita Sher-Gil painted her immortal compositions.

Years of British rule also resulted in erection of sculptures at public places, not an uncommon practice in the Empire. Most of these relics of the past are no more. Some have been conserved while others were removed.

Another prominent sculpture was that of Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928), that stood near the famous Kim’s Gun or zamazama – the surviving cannon on the Mall, Lahore. Rai, while leading a procession with Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya to demonstrate against the Simon Commission, faced brutal baton charge and died of fatal injuries on November 17, 1928.This statue is no more there and was moved to Simla and re-erected there in 1948.

The statue of Professor Alfred Woolner, professor of Sanskrit, and vice-chancellor of Punjab University (1928 and 1936) still stands in Lahore outside the University of the Punjab on the Mall, Lahore. Perhpas the only one at a public place.

The statue of Queen Victoria at the Charing Cross, installed in 1902, is in the Lahore Museum now.

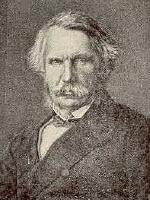

The statue of Sir John Lawrence, the first Governor of the Punjab and later the Governor General of British India (1864-69), holding a sword in one and pen in the other hand, was erected in front of the Lahore High Court. This statue, created by Sir Joseph Boehme, was inaugurated sometime in 1887. On the base of this statue was inscribed ‘Will you be governed by the pen or sword?’

The statue of Sir John Lawrence, the first Governor of the Punjab and later the Governor General of British India (1864-69), holding a sword in one and pen in the other hand, was erected in front of the Lahore High Court. This statue, created by Sir Joseph Boehme, was inaugurated sometime in 1887. On the base of this statue was inscribed ‘Will you be governed by the pen or sword?’

During 1920s, there was an agitation for the removal of this statue, which the Lahorites considered a disgrace to the nationalist movement for India’s independence. Luckily, this statue survived and probably can be found in Foyle College (now Foyle and Londonderry College) with a broken sword in one hand, damaged during an agitation in Lahore. Further, one statue of Lawrence stands in Waterloo Place in central London and another in Calcutta.

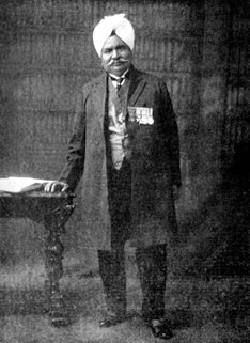

A leading philanthropist of Lahore who symbolised its cosmopolitan past was Sir Ganga Ram. Sir Ram’s statue was also on the Mall road – a befitting tribute to a man whose landmarks still survive in Lahore. What happened to this statue has been narrated by Saadat Hassan Manto, the celebrated Urdu short story writer, in one of his short stories on the frenzy of communal riots of 1947. Manto writes that an inflamed mob in Lahore, after attacking a Hindu mohalla, ‘turned to attacking the statue of Sir Ganga Ram, the Hindu philanthropist. They first pelted the statue with stones; then smothered its face with coal tar. Then a man made a garland of old shoes climbed up to put it round the neck of the statue. The police arrived and opened fire. Among the injured were the fellow with the garland of old shoes. As he fell, the mob shouted: “Let us rush him to Sir Ganga Ram Hospital.” How very ironic!

A leading philanthropist of Lahore who symbolised its cosmopolitan past was Sir Ganga Ram. Sir Ram’s statue was also on the Mall road – a befitting tribute to a man whose landmarks still survive in Lahore. What happened to this statue has been narrated by Saadat Hassan Manto, the celebrated Urdu short story writer, in one of his short stories on the frenzy of communal riots of 1947. Manto writes that an inflamed mob in Lahore, after attacking a Hindu mohalla, ‘turned to attacking the statue of Sir Ganga Ram, the Hindu philanthropist. They first pelted the statue with stones; then smothered its face with coal tar. Then a man made a garland of old shoes climbed up to put it round the neck of the statue. The police arrived and opened fire. Among the injured were the fellow with the garland of old shoes. As he fell, the mob shouted: “Let us rush him to Sir Ganga Ram Hospital.” How very ironic!

There was also a sculpture of King Edward (VII) riding a horse. This statue had been erected in front of the front of the King Edward Medical College, but it is no more there.

I respect the opinion of those who hold that sculptures are not in strict accordance with Islamic tradition. A sensible way is to preserve them as pieces of heritage like what has happened in Iran. I often wonder why public sculptures exist in Muslim majority countries such as Indonesia or Bangladesh?

Raza Rumi is an international development professional and an avid literati. More can be found at Raza Rumi’s blog: Jahane Rumi. The author is grateful to Sheraz Haider for his research on this subject.

Interesting that the toop (Kim’s gun) remains but statues of philanthropists disappear. I guess guns do express our current predicament better than philanthropy!

In Lahore at the old Charing Cross, on a grassy knoll in front of the Assembly Hall stands a beautiful white marble Gazebo or canopy that used to house the statue of Queen Victoria. The land mark locals used to refer as ‘Malka Da Buut’. In our religious fervor we removed the statue and placed a copy of Quran under the canopy in a glass box. The process is commonly known as ‘Islamisation’.

I am glad to hear that the Lajpat Rai and John Lawrence statues are safe and have been moved elsewhere. One day, I hope, that we will be able to acknowledge every part of our heritage and develop the self-confidence as a nation to embrace all aspects of our identity without thinking that doing so will somehow threaten our current identity.

Though I was only familar with the name of Sir Ganga Ram as an enginner and philinthropist who built Sir Ganga Ram Hospital and Horse train but today I got more information from your website. All the historic buildings which are the pride of lahore were designed by him. there is also Sir Ganga Ram hospital in Dehli also. We should preserve our heritage.

There is always something nice to know and learn about Pakistan on this site. I was pleasantly surprised to read this post.

Scattered around the country there are ample historic markers of the philanthropic contributions of “infidels” that need to be recognized and honored.

Those who live in the past stay there and those who learn from the past move forward. Let us hope that by honoring these great people the new generation of Pakistanis will follow their example to a better tomorrow.