I must have passed by this place countless times on my way to Abbottabad and back, and was always intrigued by its name. Khota Qabar! Donkey’s grave, that is. Why, I wondered, so much reverence for a dead donkey?

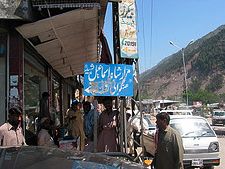

Khota Qabar lies on the Karakoram Highway, about 60 miles north of Islamabad and 7 miles short of Abbottabad. It is precisely where the road starts climbing into the mountains of Mansehra and beyond, into the picturesque Kaghan valley and the Northern Areas. I always knew it as a place where truck drivers coming up from the planes stopped to let their engines cool down, and to top up the radiators with cold water from a nearby stream, to ready their vehicles for the climb ahead. Because of the presence of trucks, several khoka restaurants have sprouted at the spot and are doing a brisk business.

Khota Qabar is so small a place that you won’t find it on any map of Pakistan. However, to my pleasant surprise, a Google search turned up the following information on the place: latitude 34.09; longitude 73.17; elevation 3,251 feet. I was impressed — with Google.

Like many other places and things in life, I took this place for granted and never bothered to enquire how or why it came to be so named. But when I did – only recently – I uncovered a fascinating story behind it. A story of a dedicated man and his mission.

The story begins, of all the places, in Rai Breli, a town in present day Uttar Pardesh, India and ends in the mountains of Balakot, a town in the far north of Pakistan. It is the story of a man named Syed Ahmed. He was born in Rai Breli in 1786. He was a deeply religious man. His life mission was to usher in, once again, the glorious Islamic past. He wanted to establish an Islamic state on the pattern of the early Caliphate, first in the subcontinent and then, possibly, in the rest of the world. To achieve this he decided to wage a jihad against the “infidels†who ruled the subcontinent then. Thus, he became one of the earliest, if not the first, native Jihadi of the subcontinent.

The story begins, of all the places, in Rai Breli, a town in present day Uttar Pardesh, India and ends in the mountains of Balakot, a town in the far north of Pakistan. It is the story of a man named Syed Ahmed. He was born in Rai Breli in 1786. He was a deeply religious man. His life mission was to usher in, once again, the glorious Islamic past. He wanted to establish an Islamic state on the pattern of the early Caliphate, first in the subcontinent and then, possibly, in the rest of the world. To achieve this he decided to wage a jihad against the “infidels†who ruled the subcontinent then. Thus, he became one of the earliest, if not the first, native Jihadi of the subcontinent.

This was the time when the Mughal rule in India had virtually ceased to exist. The Mughal Empire stretched barely beyond the present city of Delhi. The dominant powers of the time were the British Empire, represented by the East India Company, which controlled most of the Northern India, the Marhatta Empire to the south, the Sikh Empire in the north-west and Kashmir, and hundreds of minor kings, maharajas and Nawabs in various parts of the land.

Syed Ahmed understood that it was not possible to fight the British. They were better organized, better equipped and in firm control of most of the northern India. He, therefore, decided to emigrate to what is today the NWFP in Pakistan and wage a jihad from there. After beating the Sikhs in the NWFP and Kashmir, he imagined, he could then take on the British.

His choice of NWFP as a launching pad for the jihad was based on the assumptions that it was predominantly a Muslim area bordering on another Muslim state, Afghanistan, that its people had a reputation of being good warriors, and that they were unhappy with the Sikh rule and ready to take up arms against them.

Armed with these assumptions, a total faith in his mission and trust in God, Syed Ahmed and his devotees left their homes and families (Syed Sahib left behind his two wives) and embarked on a difficult and circuitous journey to Peshawar, via Sindh, Quetta, Qandhar and Kabul. Among his companions was also Shah Ismail, a grandson of Shah Waliullah of Delhi.

After reaching Peshawar, Syed Sahib tried to enter into alliances with the local chiefs and khans, often unreliable, to gain their support for his Jihad. He managed to raise an “army†of mujahideen, who engaged in a few skirmishes with the Sikhs and also launched nighttime raids on a few towns, notably Akora Khattak and Hazro. But these skirmishes and raids did not yield any strategic gains.

Most narratives on the subject, at least the one’s I have read, even though rich in trivia, are incoherent and confusing. Cutting through the web of confusion, however, one finds that Syed Ahmed Brelvi, moving from place to place for 4-5 years in the Frontier province, turned up at Balakot sometime in the first quarter of 1831. He was 46. In the process he also married a third wife, a young woman from Chitral named Fatima.

Syed Sahib’s strategy was to defeat the Sikhs at Balakot and then march on to Kashmir next door. His starry-eyed optimism is evident from one of his last letters he wrote to the Nawab of Tonk in India, who, as a gesture of support and sympathy, was housing Syed Sahib’s two wives as guests on his estate. The letter was written on 25 April 1831 (translation and paraphrasing is mine):

“I am in the mountains of Pakhli (name of the area). The people here have welcomed us with warmth and hospitality and have given us a place to stay. They have also promised to support us in the jihad. For the time being, I am camped in the town of Balakot, which is located in the (river) Kunhar pass. The army of the infidels [kuffars] is camped not too far from us. Since Balakot is located at a secure place (surrounded by hills and bounded by the river), God willing, the infidels will not be able to reach us. Of course, we may choose to advance and enter into a battle at our own initiative. And this we intend to do in the next two or three days. With the help of God, we will be victorious. If we win this battle, and, God willing, we will, then we will occupy all the land alongside the Jehlum River including the Kingdom of Kashmir. Please pray, day and night, for our victory.â€

Obviously, Syed Sahib believed in and greatly relied upon divine help and miracles.

Hari Singh was the governor of Kashmir and NWFP at the time, representing Maharaja Ranjit Singh who sat in Lahore. He was a clever and ruthless administrator. His forces under the command of Sher Singh lay in wait at Muzaffarabad. Some of his contingents had already moved to occupy the hilltop, known as Mitti Kot, overlooking the town of Balakot.

Syed Sahib expected the Sikhs to come down from their perch at Mitti Kot and attack the mujahideen. He, therefore, had the paddy fields, between the town and the hills, flooded with water, hoping that the advancing Sikhs would get mired in them and the Mujahideen could then pick them up like sitting ducks — literally. But the Sikhs had their own plans. They did not move and waited instead for the mujahideen to make the first move.

The mujahideen obliged on May 6, 1831. It was a Friday. A bizarre incident occurred that morning, which precipitated the battle. While the mujahideen were still having breakfast and, at the same time, keeping a wary eye on the movement of the enemy at Mitti Kot, one of them, Syed Chiragh Ali from Patiala, suddenly expressed a desire to eat kheer (rice pudding).

Since kheer was not on the menu that morning, Chiragh Ali fetched the necessary wherewithal and set about preparing kheer for himself. (It sounds bizarre reading about it, but people are known to do strange things in stressful conditions.)

While Chiragh Ali was stirring the pot and nervously looking at the Sikhs on the hilltop, something came over him and he shouted, “There, I see a beautiful hoor (houri) dressed in red. She is calling me!†He threw away the ladle with which he was stirring the pot, and declared that he would eat only from the hands of the hoor. With this announcement he charged headlong towards the hill. It all happened so suddenly that before anyone could realize what was happening, Chiragh Ali was in the middle of the paddy fields, struggling to run in the mud. The Sikhs who must have been watching the scene with some amusement picked him in the sights of their rifles and shot him dead — in the mud. According to the narrative, Syed Chiragh Ali was the first martyr of the battle of Balakot.

While Chiragh Ali was stirring the pot and nervously looking at the Sikhs on the hilltop, something came over him and he shouted, “There, I see a beautiful hoor (houri) dressed in red. She is calling me!†He threw away the ladle with which he was stirring the pot, and declared that he would eat only from the hands of the hoor. With this announcement he charged headlong towards the hill. It all happened so suddenly that before anyone could realize what was happening, Chiragh Ali was in the middle of the paddy fields, struggling to run in the mud. The Sikhs who must have been watching the scene with some amusement picked him in the sights of their rifles and shot him dead — in the mud. According to the narrative, Syed Chiragh Ali was the first martyr of the battle of Balakot.

What followed the shooting was total chaos and confusion. Syed Sahib, abandoning his earlier battle plan, ordered his men to attack. The mujahideen rushed forward and they, too, got mired in the muddy fields. The Sikhs then made their move. In a battle that lasted most of the day, amidst shouts of Allah-o-Akbar and wahe guruji ki fateh, Syed Ahmed and Shah Ismail were killed along with many mujahideen. The number of dead mujahideen varies, depending on the source one uses, from 300 to 1300. Whatever the numbers, the mujahideen had met their Waterloo at Balakot

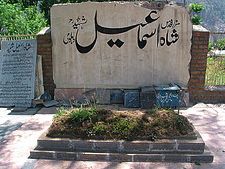

Nearly two centuries later, on October 6, 2005, an earthquake measuring 7.6 on the Richter scale shook and flattened the town of Balakot. Miraculously, however, it spared the graves of Syed Ahmed Shaheed and Shah Ismail Shaheed. Perhaps a reminder that miracles do happen. But one cannot always rely upon them.

What about Khota Qabar? Why was Khota Qabar so named?

On their way to Balkot the mujahideen had camped somewhere near present day Abbottabad. The Sikhs, in order to choke the mujahideen’s supply lines, posted troops on the hills overlooking the road that led through a gorge to Abbottabad. The mujahideen, sensing the risk of sending convoys through the gorge, cleverly, hired the services of a donkey without a handler to carry their supplies. Yes, Just one donkey.

Even though the donkey has, for some reason, become a metaphor of stupidity in our part of the world, it is not stupid at all. In fact, it has a good memory and uses it very intelligently. One of the unique traits of the donkey is that once he carries a load to a destination, he memorizes the route and does not need the help of a handler to be able to go back to the same place. Just a light kick in the back sends him trudging quietly to his destination. So, unknown to the Sikhs, this dutiful donkey trudged back and forth in the darkness of night carrying supplies to the mujhideen.

It wasn’t long before the Sikhs found out who the secret courier was. They shot him dead one night when he was carrying a load of goods through the gorge. The mujahideen mourned the loss of the donkey and honored him by burying him respectfully in a grave. The place came to be called as Khota Qabar. The grave may not have survived but the name did. Only a few years ago, someone decided to change the name to Muslimabad! Although a road sign does indicate the new name, the people in the area still know the place by its old name. And so does Google!

The above story, except the part on Khota Qabar, which is anecdotal, is based the following books:

1. Syed Ahmed Shaheed – Mujahid-e-kabir by Ghulam Rasool Mehr, 1981

2. Roedad-e-Mujahideen-e-Hind by Muhammad Khawas Khan, 1983

A few explanations about the pictures in the post would be in order:

The picture at the top left is that of the of Mitti Kot peak overlooking the town of Balakot (not in the picture). This is where the Sikh troops had taken positions.

The picture at top right is that of Kunhar River rushing past a village called BissiyaN, about 3 miles short of Balakot. It presents a beautiful sight with the snow-covered Musa ka Musalla in the background. Several relief camps for the earthquake victims are operating here. About 50 miles upstream is the famed Kaghan valley.

In the second cluster, the pockmarked rock to the left is one of the few rocks that lie at the foot of Mitti Kot hill close to Shah Ismail’s grave. The locals believe the holes on the rock-face were struck by the flying bullets during the battle. The light blue graffiti on the rock is of post-earthquake origin advertising the name of some relief organization.

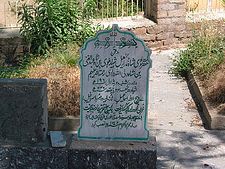

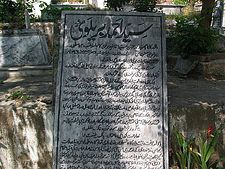

The tombstones in the bottom cluster mark the graves of Shah Ismail and Syed Ahmed, located nearly a kilometer away from each other. The one on Shah Ismail’s grave, upper left, says it was written and installed by one Anwar Ali Faridabadi in 1372 Hijri, which makes it nearly 60 years old. The one on lower left appears to have been painted in Jamaat-e-Islami colors — a reminder of a more recent jihad by the various mujahideen factions.

Nice story. Yes, we underestimate the khotta, which is a very useful animal in our world.

In the first picture, why is there that band without any trees in it… looks odd like they were cut?

Dear MQ

I have just gone through your post. Your story telling is as usual very good and enjoyable. My sincere congratulations.

This story of Syed Ahmad Shaheed reminds me the character of Don Quijote (Quichotte, Quixote) of Miguel de Cervantes. Only difference is that our Shaheed is a religious person and not funny at all. The only sympathetic and intelligent character is the brave and courageous donkey. He merits a “mazAr”!

Ahsan

Thanks for the great writeup, Mast Sahib.

The story and the details might be new to most of the us, the ‘regulars’, but the religious circles have been quoting and remembering this battle ever since it happened. Of particular inspiration is the taking part in these expeditions of Shah Ismail who was a direct grandson of Shah Wali ullah the great saint. It is said that the people of Dehli at that time offered similar ritualistic honors to the grandchildren of the great saint as they offered to the real princes of the King of the time.

Syed Sahib, it is not mentioned in this narrative, used to ‘prepare vigrously’, along with his would-be army men back in Dehli. These exercises included long runs of one-breath underwater swimming and what is the now a lost art, ‘laathi’ (baton).

Also, the Khota Qabar has another attributed history found in the mystic literature. Idrees Shah, in his book Caravan of Dreams narrates one version (see below). The Khota Qabar might have this origin.

Mast: Thanks for writing about it. I had my schooling in Abbottabad and have passed Kota Qabar thousand times. Its amazing that people remembered this donkey and named the place after it!!