Adil Najam

Our friend Babar Bhatti reports on his blog State of Telecom Industry in Pakistan that in 2007 the total number of mobile subscribers in Pakistan reached 76.6 million. He is reporting from an interesting statistical compilation of achievements compiled by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA); (more number from this report are included below).

Our friend Babar Bhatti reports on his blog State of Telecom Industry in Pakistan that in 2007 the total number of mobile subscribers in Pakistan reached 76.6 million. He is reporting from an interesting statistical compilation of achievements compiled by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA); (more number from this report are included below).

I ask the questions I do in the headline not out of cynicism but out of very honest inquisitiveness. I deal a lot with development related statistics in my professional work and for many reasons the number seems rather surprising to me. It probably is that the meaning of “subscriber” here is different from what I would have expected or that I am unfamiliar with the specifics of how this number is calculated and what it signifies. If so, I am eager to learn. I also wonder to what extent massive growth in mobile phone subscribers is necessarily good for a developing country like Pakistan?

Depending on who you want to believe the population of Pakistan is somewhere around 165-140 million. Probably closer to the latter number; some estimates would suggest even higher. If “subscriber” means the number of unique individuals who are subscribing to a mobile service (as it would in many other development contexts) it would mean that nearly half of all Pakistanis – man, woman, child, old, young, infant, newborn – are mobile phone subscribers.

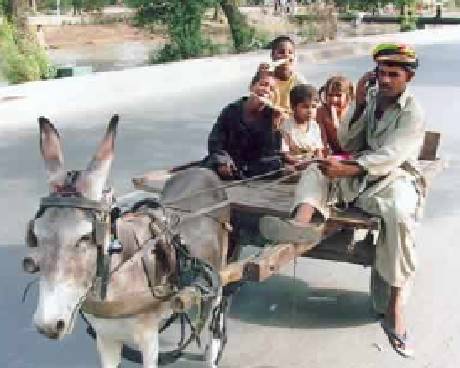

Although anyone in Pakistan knows that the penetration of cellphone to all classes – including middle and lower-middle income groups – is very high, the absolute poor (and there are still a very large number) are not likely to be subscribers. It is also likely that the penetration is much less in rural areas than in urban, that it is much much less amongst the very old and should be zero or nearly zero amongst the very young. I have seen some kids (12-15 years) with cell phone of their own, but these would be mostly in the higher economic strata and it could not be a very high number. Similarly, while the phenomenon of multiple phones per family is now dominant in many middle and most higher income groups, one assumes that it is less prevalent in the lower income groups.

Any set of reasonable assumptions about these are related variables would suggest that the wording from the PTC is potentially misleading. It is more likely that the number is really of the cell phone “numbers” issued and technically in use. The fact, however, is that many many of these “issued” numbers would not really be in use. However, given the “SIM culture” and the rather common practice of holding multiple SIM cards and numbers (I have two myself, and I don’t even live in Pakistan!) it would not be surprising that the real “subscribers” are much less – although a still impressive number.

But that is my second, and more important question. Should we be really be impressed – in a development perspective – if the number of mobile subscribers are high in a developing country? It certainly signifies good business for the industry, but what does it say about the country and national development?

There are those who argue in the literature that the rapid growth of such services in developing countries signifies the failure of governments in providing essential infrastructure. This argument is far more valid in the water sector. A very high number of urban Pakistanis, including very poor ones in katchi abadis buy water from non-municipal sources (private tankers, tubewells, etc.). This does not signify a high private demand for water services as much as it signifies low government provision of the service. The same is true for energy – both in terms of the number of people (even in middle income groups) who have to expend money on private generators or other sources and also those who have to buy fuel wood. At least in the essential services category (cell phones are not really there) this means that significant portions of one’s income have to be spent on buying essential services (at higher prices; e.g., in the water and energy sectors). The poorer you are, the lower your disposable income, and the greater the proportion of that income being spent on these services, which you have to buy privately because the public provision is inconsistent or non-existent.

This is not without relevance to the cellphone situation. For my parents and many others I know, the cell phone is as much a means of security – in an increasingly insecure time – as a means of communication. This is true elsewhere too, but it is even more true in Pakistan. Similarly, the “need” for cellphone increases as other means of communication become unpredictable. E.g., the land-line system. There is also, always, the issue of improper marketing and the consumer being forced into spending much more than they should or thought they were.

The point of all of this is to wonder whether cellphone uptake actually translates to an increase of net developmental productivity – i.e., are people able to do more and make more in terms of their livelihoods – or is it that it has become a new “necessity” and “cost.” (For example, “everyone needs a cellphone now because everyone else has it and not having one is a barrier to entry”). If, indeed, it is that a new “need” and “cost” has been created then that only means that the net “cost of living” has gone up. And, especially for the poor more and more of their disposable income is diverted to this “need” that may not be adding to their productivity or livelihood, but not having which would hurt them. This at a time when the cost of living is already high and economic survival at the individual level under stress (remember where Karachi was on the Global Liveability Index?).

Of course, if the ability of having a cell phone at low cost does, in fact, translate into increased livelihoods (i.e., that the cost of cellphone per person is less than the increase in earning per person because of that cellphone) then the net development benefit would be positive. Even if not, one could argue that development benefits should include (I agree) the non-monetized convenience of having a cellphone; and if this benefit outweighs the costs that society as a whole is better off. What I would like to know whether these benefits do, in fact, outweigh the costs? Or, have we crossed some threshold of excessive cellphone ownership where, despite seemingly low costs, the marginal benefit of ownership no longer exceeds the marginal costs?

Of course, if the ability of having a cell phone at low cost does, in fact, translate into increased livelihoods (i.e., that the cost of cellphone per person is less than the increase in earning per person because of that cellphone) then the net development benefit would be positive. Even if not, one could argue that development benefits should include (I agree) the non-monetized convenience of having a cellphone; and if this benefit outweighs the costs that society as a whole is better off. What I would like to know whether these benefits do, in fact, outweigh the costs? Or, have we crossed some threshold of excessive cellphone ownership where, despite seemingly low costs, the marginal benefit of ownership no longer exceeds the marginal costs?

I do not wish the argument to be taken wrongly. Anyhow, it is more of a question than an argument.

I appreciate that in many developing countries the availability of cellphone cheaply does allow new opportunities to large number of people – including the poor – who did not have those opportunities before. It is also, of course, wonderful for the telecommunication companies and those who work in these companies and related industries (The PTA report – below – says that 1 million new jobs were created). None of this I dispute. The question is about the overall development impact, especially when things overheat. Good? Bad? or Ugly?

So, there. I really would love to get a serious discussion and answers from those who are more deeply involved in this sector. As you think about that, here are some other highlights from the new PTA report:

- Overall teledensity of Pakistan reached 52.8% in December 2007.

- During 2006-07 total telecom revenue was Rs 236 billion.

- Total telecom investment during the year was US $ 4.12 billion and the share of telecommunication sector in GDP was 2.0%.

- Telecom companies have invested over US$ 8 billion during the last four years, mobile sector investment share accounts for 66% of the total investment.

- During 2006-07 the revenue of mobile industry was Rs.133 billion, an increase of 48% from pervious year.

- China Mobile investment is US$ 704 million during 2006-07 for expansion of CMPak networks.

- Mobile Sector paid approximately Rs. 63 billion taxes to the National Exchequer during the year 2006-07.

- Upto December 2007 cellular subscribers in Pakistan reached 76.6 million.

- On average 2.3 million subscribers were added every month during 2006-07.

- Upto June 2007 6,000 cities/towns/villages covered by mobile operators.

- Upto December 2007, total cell sites 17,779 all over Pakistan.

- Today mobile network coverage is reaching to almost 90% of the total population

- The telecom sector received above US$ 1.8 billion FDI, 35% of the total FDI.

- Telecom sector contributed Rs. 100 billion in the national exchequer in terms of taxes and regulatory fee which was 32% higher than the previous year.

- GST/CED collection during the period reached Rs. 36.28 billion.

- Over one million jobs have been created since the deregulation of the telecom sector.

- Rural Telephony Project launched during the year under which 400 Rabta Ghar (Telecentres) are being established in rural areas.

- Total investment in the LDI sector grew upto US$ 603 million in 2007.

- New LDI sector revenue stood at Rs. 15.3 billion.

- At the end of 2006-07 total fixed line connections stood at 4.8 million where as the teledensity is 3.04%.

- There are total of 387,490 PCOs including WLL based PCOs which are working across Pakistan at the end of year 2006-07.

- By June 2007, Broadband subscribers reached 71,000 and 65% of Pakistani broadband users enjoy DSL broadband technology.

- The total teledensity of AJK & NAs was 20.1 in 2006-07 as compared to 3.6 in 2005-06. Overall growth in teledensity in the region due to deregulation is 450%.

- By June 2007, Cellular subscribers reached 912,227 all across AJK & NAs.

Much has been said more can be said in analysing this phenomena. Indeed a phenomena. Here I only wish to share a news item in the press just a few days ago.

The PTA has served notice on the Cell phone servers that they donot keep a record / verification of who is purchasing the SIMs. Does that mean people of all interests and motivations have a free hand in obtaining this very powerful technology??

I know for a fact that in the US you cannot have a Cell phone from anyone without proper identification, i.e. your Social Security information. That means every connection is accounted for and traceable.

Adil, even after you rephrased the question the answer is still the same, and still very obvious in my opinion. The reasons have been laid out in good detail by many of the responses.

As for the youngsters (or cheating spouses as one reader pointed out). Lets not blame the cell phones for that. If cell phones weren’t available they would have found another way. They just need a lesson in shame and respect.

The digitalization of and deregulation of telecom sector undoubtedly brought a positive externalities in general and rural areas in particular. It has bridged the gap of connectivity between rural and urban population. For the past several years telecom sector was top priority of our successive governments and it somehow is successful in achieving those targets. But we need to keep this perspective that the objective of this expansion was to enhance investment in the sector and increase subscriber for revenue collections rather than connecting the people.

At the same time our government neglected those fundamental sectors which were required to be given more attentions such as food, water, health, education, democracy and judiciary etc.

The lesson we need to learn from this success story is that effective connectivity is useless unless the basic needs of people are not met. Today we are well connected but the social fabric of our society is scattered. This cell revolution could not bail us out of this Atta, power, gas crises. Unfortunately, government tried to use the same framework of deregulation in basic needs which ended up in chaos and crises. There is a an urgent need to rewrite our development paradigm where basic issues need to be given top priority with strong government intervention.

I am more than glad to see people’s access to get connected in an efficient way but it does not lessen their frustration when they are denied and are unable to exercise their right to food, right to education, right to healthcare, right to justice, right to freedom of expression and so on so forth.

The digitalization of and deregulation of telecom sector undoubtedly brought a positive externalities in general and rural areas in particular. It has bridged the gap of connectivity between rural and urban population. For the past several years telecom sector was top priority of our successive governments and it somehow is successful in achieving those targets. But we need to keep this perspective that the objective of this expansion was to enhance investment in the sector and increase subscriber for revenue collections rather than connecting the people.

At the same time our government neglected those fundamental sectors which were required to be given more attentions such as food, water, health, education, democracy and judiciary etc.

The lesson we need to learn from this success story is that effective connectivity is useless unless the basic needs of people are not met. Today we are well connected but the social fabric of our society is scattered. This cell revolution could not bail us out of this Atta, power, gas crises. There is a an urgent need to rewrite our development paradigm where basic issues need to be given top priority.

I am more than glad to see people’s access to get connected in an efficient way but it does not lessen their frustration when they are denied from their right to food, right to education, right to healthcare, right to justice, right to freedom of expression and so on so forth.

Nothing could be better than this telecom revolution. As for the figures, one may have many doubts, but when I see that even my cook has a mobile and a SIM card, then I start believing the numbers.

As for productivity, it definitely improves. With people rather than going to the market to figure out the rates and waste their time in doing so just give a ring and get the desired information. When earlier a gardener or a plumber could do one or two jobs a day, can now do more because he/she gets the appointments on the mobile phone.

It obviously would contribute to development in more ways than one. Firstly, it would spawn business ventures around the mobile phones. New mobile phones might become popular, which might have greater processing speed making them suitable for showing movies, doing all the online stuff, automatically downloading useful information for the owner given his/her interests, learning the behavior of the ownder to optimize performance, so on and so forth. Only countries, which have a huge number of mobile phones would be able to establish such technologies since only they would be able to create economies of scale.

Also with the mobile phone market saturating, companies would have to come up with new technologies to survive in such a big market. The next thing I see is the boom in the sales of computers, both desktop and laptop, in Pakistan. With computers becoming dirt cheap a lot of them would be sold in the Pakistani market, and people already having mobile phones would have more incentive to spend on the computers than on the mobiles. Computer technologies would develop around the Pakistani market. Like laptops with long battery life, even cheaper versions of laptops with linux and AMD processor, software versions in local languages. For instance, one might start seeing windows and office versions in Urdu or other local languages. That can only be done if the local market is large enough to provide economies of scales to the software and hardware developers.